- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 4101

What Russian Oil Flows Reveal About Syria and Lebanon’s Energy Sectors

Greater U.S. attention to oil and trade dynamics in Syria and Lebanon can help prevent adversarial states like Russia and illicit networks from exploiting weaknesses there.

This month, Syria loaded its first crude oil export cargo since the Assad regime’s fall—in fact, its first in more than a decade. Although this was a significant outcome of loosened U.S. and EU sanctions, the cash-strapped country still needs high volumes of oil imports as it attempts to rehabilitate its energy sector. Amid these conditions, Russia, whose oil and gas industry is subject to Western restrictions, has emerged as a key supplier of inexpensive oil.

In the East Mediterranean region, such oil is supplied directly from Russian ports or ends up at regional transshipment hubs (where it is transferred from one ship to another) or ports that serve as re-export hubs. Syria is not the only struggling country in which such imports have been noticeable; Lebanon has been grappling with a financial crisis since 2019, and the government has been regularly receiving Russian oil cargoes for power generation. In the Syrian market, these oil flows raise questions about Moscow’s influence in the post-Assad era, while in Lebanon, they bring attention to the regional oil trade itself, as seen in Beirut’s complex 2021 deal with Iraq (see below).

The Trump administration has been active diplomatically in both countries, though under differing circumstances. By keeping abreast of local oil and trade dynamics, U.S. officials could help shed light on each country’s energy sector struggles and highlight the vulnerabilities that allow adversarial states and illicit networks to exploit ongoing delays in economic and institutional development.

Russian Oil Flows to Syria

Shipping data reveals that a number of crude oil tankers involved in the Russian oil trade have been sailing to the East Mediterranean since early this year, with their cargoes ending up in Syria. (The Washington Institute first brought attention to this situation in March.)

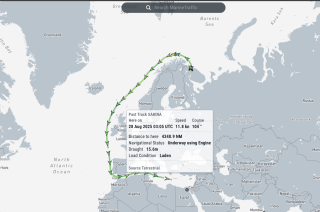

For example, at the same time that Syria was exporting its above-mentioned first cargo of heavy crude from Tartus—specifically, 600,000 barrels loaded onto the Greece-flagged Nissos Christiana (IMO identification number 9694658)—the U.S.-sanctioned, Comoros-flagged tanker Sakina (IMO 9530917) was berthing in Syrian waters to discharge its cargo of Russian oil following a partly covert voyage. After leaving the Russian port of Murmansk on August 13, Sakina switched off its Automatic Identification System on August 28 to avoid detection while sailing near Crete and pretending to be headed for Port Said, Egypt, based on tracking done by the author (see map below).

TankerTrackers.com, a company that has been tracking oil flows to Syria for several years, confirmed that the vessel was in Syrian waters as of September 1 to discharge at the Baniyas Single Buoy Mooring (see satellite image below). The ship reappeared on tracking systems on September 5 while off Cyprus.

This was not the first Russian oil cargo transported to Syria via tankers sanctioned by the U.S. Treasury Department. Recent instances include the Gambia-flagged tanker Fearless (IMO 9513139), which carried some 700,000 barrels of Russian crude to Baniyas in June according to Kpler. Overall, Syria has imported around 12 million barrels of crude from Russia this year according to TankerTrackers.com. Moscow has been supplying Damascus with refined oil products as well, including fuel oil and diesel, which Syria has also imported from a few other countries (e.g., Turkey).

Since the fall of the Assad regime, some countries have expressed interest in partnering with Syria’s new government on energy issues, while others have offered immediate assistance on natural gas and electricity supplies (e.g., Azerbaijan, Qatar, Turkey). But Russia remains the key supplier of crude oil given its discounted cargoes and ability to maintain consistent supplies when Syria needs them most.

Indeed, as Damascus gradually rebuilds the war-ravaged country amid persistent security and social challenges, it will need high volumes of oil imports. From this perspective, its recent export cargo is a mere drop in the bucket and should not be viewed as a sign of Syria’s recovery. As MEES has pointed out, the country’s two existing refineries have simple configurations that are not designed to process Syrian heavy crude due to its characteristics (e.g., high sulfur content). Thus, exporting Syrian heavy crude to regional and complex refineries would be a better solution. For instance, based on data from MarineTraffic, the Nissos Christiana reached Italy’s Sarroch port on September 10, most likely to discharge its cargo of Syrian crude at the local refinery. (Some media outlets reported that the buyer was the giant trading firm Vitol, though the Syrian government referred to a buyer named “B Serve Energy.” This could suggest the shipment was purchased indirectly.)

Although Syrian energy exports may continue, they will likely be sporadic at best. In June—after Washington issued a 180-day waiver of its Caesar Act sanctions—Damascus exported a cargo of the crude oil product naphtha, which was carried by the Marshall Islands-flagged Velos Fortuna (IMO 9347310) and ended up at a European port, according to data from Kpler. Yet the volume and benefits of such exports will depend on both market conditions and Syria’s ability to consistently produce them. Its oil output as of 2024 was roughly 35,000 barrels per day, far less than the estimated 350,000 b/d it was producing in 2011. Production will remain volatile, as the country is far from stabilized.

Russian Oil Flows to Lebanon

The circumstances are different in Lebanon, where Russian oil is being imported for use by the country’s deeply mismanaged power generation sector. Last month, Lebanon received three cargoes of gasoil and fuel oil, which originated from the Russian ports of Primorsk and Novorossiysk and were transported by the Palau-flagged Fidan (IMO 9423736), the Sierra Leone-flagged Prometei (IMO 9296597), and the Panama-flagged Hawk III (IMO 9260263). While the first two tankers were able to offload without issues, the Hawk III was caught in a politically motivated controversy over its oil cargo, the details of which have not been confirmed. After arriving in Lebanese waters on August 21, the vessel remained anchored and unable to discharge until earlier this week, despite the country’s urgent fuel needs. According to various tracking data, these Russian cargoes were destined for four Lebanese power plants: Zahrani, Deir Ammar, Zouk, and Jiyeh.

Between 2017 and 2021, Lebanon regularly imported Russian-origin oil products, but this changed after 2021 amid a deepening financial crisis and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Importing these products is not illegal today—Saudi Arabia imports Russian fuel oil for power generation in the summer, and other countries still engage in the practice as well. In Lebanon, however, such trade raises questions about how the cargoes are bought and priced because Russia now offers heavy discounts. In 2021, Lebanon and Iraq reached a convoluted deal in which Baghdad initially supplies Beirut with fuel oil, which is then swapped by third parties for other oil products, potentially including Russian oil. The swap is done by private companies because the Iraqi fuel oil’s specifications do not match those needed to run Lebanese power plants. Yet in spite of this deal and other stopgap measures (e.g., gasoil supplies supported by Kuwait), Lebanon continues to suffer from severe power outages.

Joe Saddi, who took charge of the Energy Ministry in Beirut earlier this year and is close to the Christian “Lebanese Forces” party, now has the difficult task of addressing both an acute energy crisis and chronic corruption. For more than a decade, the ministry had been under the control of officials affiliated with the Free Patriotic Movement (a strong Christian ally to Hezbollah in the past), resulting in multiple scandals. In 2023, the U.S. Treasury sanctioned two Lebanese figures for using private companies to secure government contracts through a “highly opaque public tendering process.” Worse yet, the fuel they imported as part of this scheme was tainted, causing damage to power plants.

Policy Recommendations

Because Damascus will likely continue importing discounted Russian oil, Washington will need to monitor this practice closely to ensure Moscow does not use it to exert undue influence in post-Assad Syria. Russia still retains two military bases in Syria (including its strategic Mediterranean naval base in Tartus), so its desire and capacity to sway Damascus will not conveniently disappear just because the regime has changed.

Syria’s broader oil trade should be closely watched as well, including the identity of any intermediaries brokering oil deals between the government and energy firms. This will help ensure that no illicit networks profit from the country’s current weakness and decades-long corruption, which could grow under the new authorities. Some regional traders may seek to exploit the status quo. Many foreign companies may still regard Syria as a high-risk country, and since not all sanctions have been lifted, they may feel compelled to avoid dealing directly with it, raising the need for go-betweens. Washington should therefore watch out for any illicit networks that try to exploit this state of affairs, similar to those it sanctioned in the past for involvement in complex, corrupt energy schemes in Lebanon.

As for Beirut, U.S. attention has rightfully focused on disarming Hezbollah of late, but this alone will not stabilize the country. Nefarious actors have long benefited from corruption, especially in key institutions like the Energy Ministry. In 2020, for example, the previous Trump administration sanctioned Lebanese officials for involvement in various schemes that benefited elites. Because such corruption is antithetical to economic development, the Lebanese government cannot treat Hezbollah’s disarmament as its sole mission—it must also work on a clear set of urgent, absolutely necessary reforms, especially in the energy sector. Minister Saddi recently stated that he will be acting on important electricity regulation legislation (Law 462/2002) that was passed more than two decades ago but never implemented. This effort and the wider mission to reform and restructure Lebanon’s energy sector are fraught with political obstacles, so Washington should do everything it can to publicly support such measures.

Noam Raydan is a senior fellow at The Washington Institute and co-creator of its Maritime Spotlight platform.