- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 4131

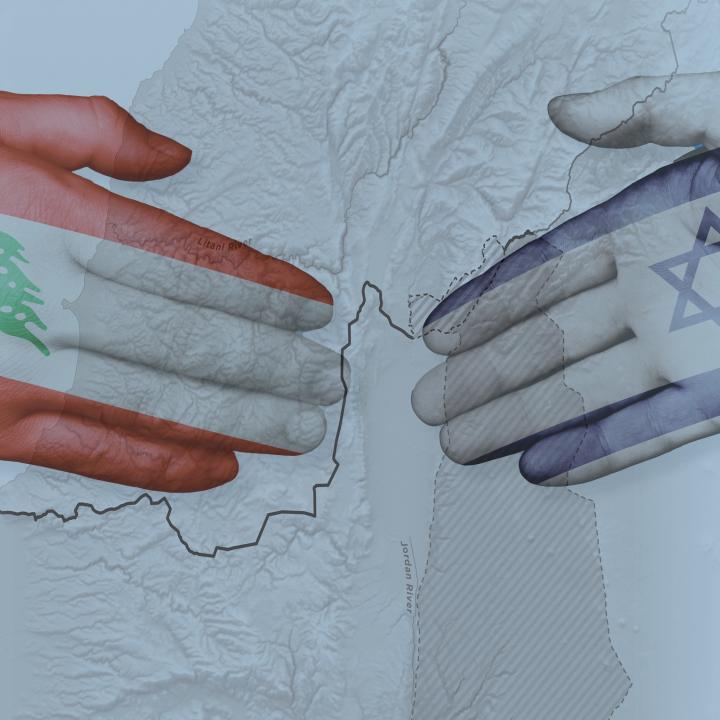

Is There a Pathway for Lebanon-Israel Peace?

A Lebanese legislator explains why disarming Hezbollah and discussing peace terms with Israel is so crucial to his country’s future, while a separate expert panel discusses the roadblocks to progress.

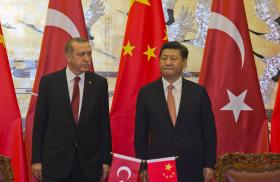

On November 6, The Washington Institute held a virtual Policy Forum that included a one-on-one conversation with Fouad Makhzoumi followed by a separate panel discussion with Eran Lerman and Hanin Ghaddar, coauthor of the new Institute report “A Roadmap for Israel-Lebanon Peace.” Makhzoumi has served since 2018 as an elected member of the Lebanese parliament. Lerman is vice president of the Jerusalem Institute for Strategy and Security and former deputy National Security Council director for foreign policy and international affairs in the Israeli Prime Minister’s Office. Ghaddar is the Friedmann Senior Fellow in The Washington Institute’s Rubin Program on Arab Politics. The following are rapporteur’s summaries of each discussion.

Summary of Fouad Makhzoumi’s one-on-one conversation with Washington Institute executive director Robert Satloff:

Since 1984, Hezbollah, backed by Iran and Syria, has effectively taken control of Lebanon’s political and security structures, undermining state sovereignty and consolidating power through its militia and deep-state networks. To restore national integrity, Lebanon must disarm the militia and reassert the principle of “one state, one army, one presidency.” As long as Hezbollah maintains its weapons and the ability to unilaterally wage war with Israel, the Lebanese state cannot be rebuilt.

Despite claims by the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) that they have achieved 85 percent of their objectives under the ceasefire agreement signed on November 27, 2024, Hezbollah continues to rearm, and Israel continues to strike the group’s positions and weapons caches. This underscores the government’s lack of political will and its continued pattern of making commitments it fails to uphold. The international community should pressure Beirut to eliminate Hezbollah’s presence south of the Litani River by the end of this year and achieve complete disarmament six months after. Failure to do so risks further Israeli retaliation and deeper instability.

The prospect of peace with Israel offers Lebanon a path out of perpetual destruction and economic hardship. Lasting stability would end the cycle of wars followed by efforts at rebuilding; it would give the country a firm basis on which to attract the investments and diaspora engagement that are vital to national prosperity. True sovereignty requires full border demarcation with Israel, Syria, and Cyprus to remove the pretexts that Hezbollah exploits to justify armed resistance. Beirut should also work with international allies to suspend the Arab League boycott of Israel, which Hezbollah has used to silence advocates for peace. Israeli progress on the Palestinian issue would likewise help remove a key pretext used in Lebanon to oppose or delay peace with Israel.

Moreover, despite contributing nearly 30 percent of the country’s GDP and acting as a crucial force for reform, the Lebanese diaspora has been marginalized by the political system, limiting its participation in national decisionmaking. Ensuring transparent elections and the right of full diaspora participation is essential to have a fully legitimate government.

All Lebanese look to the United States as a key partner. Washington has played an important role in supporting the country’s army, schools, and institutions, and the Trump administration has invested unprecedented energy there by dispatching multiple envoys to address Lebanese issues. This presents a rare opportunity for meaningful change. However, Lebanon must demonstrate genuine political will by disarming Hezbollah, ending illicit cash flows and smuggling, and confronting corruption. The Lebanese people are exhausted by endless wars that serve foreign agendas; now is the time for a new era of peace with Israel.

Summary of the panel discussion between Hanin Ghaddar and Eran Lerman:

Hanin Ghaddar: A significant gap remains between Israelis and Lebanese regarding the prospects for peace. While many Lebanese share a genuine desire for peace, that sentiment has yet to be heard or trusted by the Israeli public. For this perception to shift, Lebanon’s leadership must demonstrate concrete political will.

From Israel’s perspective, Beirut appears either unwilling or unable to act, reinforcing doubts about its ability to deliver on disarmament and peace. Yet the current climate represents a historic change. Before the Gaza war, peace with Israel was a taboo subject in Lebanon, only whispered in private spaces; since then, it has entered public debate in national media and political discourse. Many Lebanese now view peace as the only viable path toward stability and prosperity. Even within the Shia community, where hostility toward Israel was fiercest, there is growing recognition that Hezbollah’s approach has failed. After years of destruction and loss, more people see peace, not resistance, as the only way to end wars.

Yet the current talk of peace must be translated into action. Without tangible measures on multiple issues, Lebanon risks provoking further escalation from Israel. Disarming Hezbollah remains the most essential step. If the government refuses to confront Hezbollah militarily, it must target the political, financial, and logistical infrastructure that protects the group’s weapons. Equally critical is abolishing the “anti-normalization” laws that criminalize Lebanese engagement with Israelis. These outdated laws enable Hezbollah to suppress reformists and silence advocates for peace.

More broadly, Lebanon’s leaders must use public messaging and/or diplomatic channels to communicate a credible willingness to pursue negotiations with Israel. This is the only way to convince Jerusalem that these efforts are real and not just symbolic.

In short, three steps are essential to drive progress:

- Washington and its partners should establish clear deadlines and incentives related to the existing ceasefire agreement, which currently lacks any timeline.

- The United States should design a framework combining consequences and incentives: namely, imposing sanctions on those who block disarmament or oppose normalization, and awarding reconstruction aid for measurable progress.

- Lebanon should abolish the anti-normalization laws and take other incremental steps to ease communications with Israel.

Progress also depends on internal reform. The Amal movement and Speaker of Parliament Nabih Berri still dominate Lebanon’s politics, controlling elections and maintaining Hezbollah’s armed power. Amal and Hezbollah have the funds and weapons to intimidate dissidents and buy votes, making free and fair elections impossible amid Hezbollah control of Shia communities. Accordingly, Beirut should postpone national elections until the militia is disarmed and the LAF stands as the country’s sole military authority. Linking disarmament to future elections would ensure a level political playing field. Only then can Lebanon reclaim sovereignty, rebuild trust, and emerge as a genuine partner for regional peace and prosperity.

Eran Lerman: Currently, Israeli politics are intensely preoccupied with the aftermath of the Gaza war—recovering hostage bodies, managing a domestic governance crisis, and maneuvering for the coming election year. As such, Lebanon is not a strategic priority for most Israeli policymakers right now. Neither a strong pro-peace nor pro-war constituency is actively pushing a Lebanon agenda; instead, many see the issue as one the Israel Defense Forces should manage.

Moreover, politically driven (and seemingly not well-founded) criticism of the 2022 maritime boundary agreement has reinforced perceptions that Jerusalem yielded to Hezbollah pressure. This line of thinking has increased Israeli skepticism about further dealmaking with Lebanon and prompted a careful, slow approach to any new initiatives.

Questions also persist about the LAF’s readiness to implement orders. In particular, Israelis worry about the loyalties of Shia military personnel, fearing that intercommunal fractures could precipitate violence inside Lebanon and further complicate the prospects for durable peace.

Thus far, Israel has pursued a campaign of limited escalation characterized by precision strikes on specific Hezbollah sites, orders for civilians to vacate targeted buildings, and efforts to degrade the group’s personnel and local arms production. The objective is to hinder Hezbollah’s ability to rebuild its infrastructure without provoking full-scale war. Although Israel is weary from two years of conflict and does not seek escalation, it maintains escalation dominance and is prepared to use it if Hezbollah’s challenges to the ceasefire agreement reach a boiling point.

Going forward, Beirut could attract more Israeli attention through meaningful peacemaking steps such as repealing the anti-normalization laws, which would signal seriousness and open space for engagement. Joining a regional institution such as the East Mediterranean Gas Forum could also create an umbrella under which Lebanese and Israeli officials are able to engage without formal bilateral normalization.

The United States and other international actors can contribute to this process by coordinating with potential donors, particularly Gulf states, asking them to pledge investments linked with measurable steps toward disarmament and, eventually, normalization. Washington could organize a package of economic incentives and security guarantees tied to specific timelines and Lebanese government accountability.

Yet Beirut should realize that U.S. attention and resources are heavily committed to Gaza, and Washington’s political appetite for a large-scale Lebanon initiative remains limited. If Lebanese leaders demonstrate concrete will by dismantling militia infrastructure, abolishing laws that suppress dialogue, and empowering the LAF to establish a monopoly on force, then international support could follow. Otherwise, Israel retains the capacity for a decisive campaign whose goal would likely be to decimate Hezbollah up to the Awali River, not just the Litani—after which the LAF would have no excuse to avoid dealing with what’s left of the group.

This summary was prepared by Sarah Boches. The Policy Forum series is made possible through the generosity of the Florence and Robert Kaufman Family.