Pursuing even incremental steps will be difficult in a country long dominated by Iran’s chief regional proxy, but the two countries’ leaders have cracked the door open for future diplomacy.

While global attention is focused on the potential for ending the Gaza war, a refreshingly positive discussion has also emerged about the possibility of peace on Israel’s northern front with Lebanon. A long road separates hopeful talk from actual diplomatic moves, but for the first time in decades, peace itself is no longer taboo in Lebanon, triggering a serious national conversation about a topic once only mentioned in whispers.

Talking Peace

Since the November 2024 Lebanon ceasefire with Israel, the idea of peace has featured in public discourse in Lebanon, appearing in television debates, newspaper articles, and interviews with officials. Two factors are at play. First, Hezbollah’s military defeat undermined the appeal of the long-dominant “resistance” rhetoric and convinced a broad swath of Lebanese that only peace could end the wars that have pummeled the country for the past four decades. Second, the Trump administration’s heavy emphasis on regional peacemaking, evidenced by the president’s personal commitment to expanding the Abraham Accords, made the possibility of peace with Israel real and tangible.

These trends were reflected in unusual statements by leaders of the two long-warring countries. In his otherwise bellicose UN General Assembly speech on September 26, 2025, Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu extended an olive branch to Lebanon, commending its government for committing to disarm Hezbollah and suggesting that peace between the two nations “is possible.” While making clear that Beirut needs to take “genuine and sustained action to disarm Hezbollah,” Netanyahu outlined a future of Israel-Lebanon peace under the umbrella of an expanded Abraham Accords.

Earlier that same week, on September 23, Lebanese President Joseph Aoun included a reference to peace in the very first sentence of his General Assembly speech: “I stand before you today talking about peace.” This followed his speech a few days earlier at an Arab-Islamic summit in Doha in which he affirmed Lebanon’s willingness to reach peace with Israel based on the two-decade-old Arab Peace Initiative, a consensus position in Arab politics but not one Lebanese leaders often emphasized when Hezbollah was ascendant. In mid-October, after President Trump’s triumphant visit to Jerusalem and Sharm al-Sheikh, the Lebanese leader said his country and Israel need to negotiate because their differences have not been settled by war. Shortly thereafter, he urged indirect talks with Israel, noting that his country “cannot be outside the current path in the region, which is the path of crisis resolution.” Even Lebanon’s prime minister, Nawaf Salam, whose political origins are leftist and pro-Palestinian, has publicly entertained the idea of peace with Israel in the context of the creation of an independent Palestinian state.

Such statements from the two leaders cannot be delinked from the Trump administration’s own peacemaking ambitions. As President Trump said in his Jerusalem Knesset speech, “My administration is actively supporting the new president of Lebanon and his mission to permanently disarm Hezbollah’s terror brigades. He’s doing very well. And build a thriving state at peace with its neighbors, and you’re [Israel is] very much in favor of that, I know...Good things are happening there, really good things.” This follows such statements as those by Middle East envoy Steve Witkoff, who in a March 2025 interview expressed optimism about a future Israel-Lebanon peace deal and suggested peace could offer Lebanon a path toward political and economic stability. “Imagine if Lebanon normalizes, Syria normalizes, and the Saudis sign a normalization treaty with Israel because there’s a peace in Gaza...It would be epic,” Witkoff continued.

Challenges and Opportunities

The main obstacle preventing the leap from rhetoric to peacemaking is Hezbollah and its allies in the Amal movement. Even in its weakened state, Hezbollah remains armed and dangerous, able to cow other political forces in the country and finance the rebuilding of its arsenal. In this regard, disarming Hezbollah is the main prerequisite for peace.

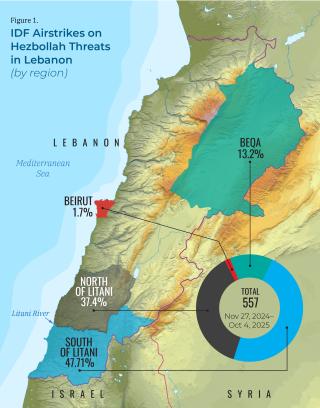

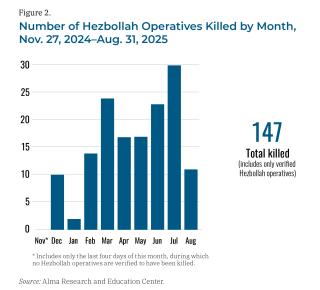

Despite this necessity, Lebanon’s political and military leaders have signaled their reluctance to use the full power of the state and army to implement Hezbollah’s disarmament, which should extend as well to twelve Palestinian refugee camps within its territory. This hesitancy will likely be especially apparent after January 1, 2026, when according to the Lebanese government’s disarmament plan, the focus should turn to Hezbollah’s weapons facilities north of the Litany River. If, at that time, disarmament remains stalled, the prospect of Israel launching an operation to complete the mission itself will become substantially more likely, as U.S. envoy Tom Barrack recently warned (see figures 1 and 2 for Israel’s anti-Hezbollah attacks since November 2024). Hamas has also refused to disarm in Lebanon’s refugee camps, posing a separate difficulty.

In light of these challenges, one way to avert a catastrophic resumption of war would be for Lebanon and Israel to begin their own direct, if incremental, peace process. Movement between the two countries would not substitute for disarmament, but if pursued as an alternative to Israeli military action against Hezbollah, the fact of the talks would undermine Hezbollah’s effort to claw back its political influence and demonstrate for the Lebanese people the potential benefits of peacemaking.

At the moment, while Lebanese leaders may be open to discussing the idea of peace, in practice they appear to be linking their own willingness to engage in diplomacy to Saudi Arabia’s posture, which requires an end of the Gaza war and a pathway to Palestinian statehood. And, of course, there remains the issue of Israel’s continued control of several positions inside Lebanese territory. But the imminence of another round of disastrous warfare may be enough for Aoun and Salam to reconsider, put Lebanese national interests first, and choose what is currently unpalatable—diplomacy with Israel.

Alternative Models?

Some in Lebanon appreciate that building a relationship with Israel is preferable to another war, but they are looking for alternatives short of full peace. In this regard, two episodes from Lebanon’s history are now frequently cited in public debate—although both are flawed models:

- The 1949 armistice. This agreement committed Lebanon to prevent its territory from being used for attacks on Israel and defined both a boundary between the countries, often called the Blue Line, and a demilitarized zone in disputed areas, particularly around villages straddling the border. The armistice failed because Lebanon remained formally at war with Israel and could not control nonstate actors on its soil; successive wars—first with the Palestine Liberation Organization and then with Hezbollah—rendered it moot. The example shows that unless an agreement binds Lebanon to an enforceable peace, it will not survive a weak state, armed militias, and a country divided by sectarian politics.

- The May 1983 agreement. This U.S.-brokered accord—produced by the only official direct negotiations between Lebanon and Israel—aimed to end the state of war between the two countries following the Israeli invasion in 1982. Although not a full-fledged peace treaty, it did provide a framework for establishing normal relations, including liaison offices, trade, and movement of people. Closely associated with the Phalangist-dominated government at the time, the agreement was annulled just a year after its signing under pressure from Syria’s Assad regime and its Lebanese allies.

Other voices in Lebanon suggest that instead of looking to the past, the country should recognize in the Abraham Accords a path to securing the country’s political, security, and economic interests. Unlike the 1949 armistice or the May 1983 accord, this path would require a commitment to full peace—substantial concession in exchange for substantial benefit.

Overcoming the Anti-Normalization Law

The idea of launching peace talks to signal Lebanon’s peaceful intent and avoid renewed war with Israel faces a uniquely Lebanese impediment—the current speaker of parliament, Nabih Berri. A longtime Hezbollah ally, the eighty-seven-year-old Berri is well known for shifting his stances with the political winds, whether local or regional. From his perch, Berri could prevent the government from pursuing peace talks, potentially until the outcome of the next legislative election, which is scheduled for May 2026.

Even until then, Lebanon has other significant ways to signal its peaceful intent. One would be to address the country’s draconian laws banning any communication between Lebanese and Israelis, whether direct (person-to-person) or electronic (via telephone or online), anywhere in the world. Because the legal language is so broad and imprecise, judges have wide discretion to classify virtually any contact with an Israeli as espionage or treason and to impose penalties as severe as lengthy prison sentences or even capital punishment.

Abolishing these laws—or at least severely restricting them to legitimate national security cases—would send a powerful message about Lebanon’s openness to people-to-people communication on which a peace movement could be built. It would also have the effect of protecting civil activists committed to pushing back against Hezbollah’s forever-war “resistance” narrative. While the current Berri-controlled parliament is unlikely to abolish or amend the laws, the Lebanese government does have the power to control their enforcement, which it could use to send the appropriate signal.

Incremental Steps on the Road to Peace

Even in advance of an agreement, Lebanon and Israel could cooperate in numerous areas, thus building confidence and improving prospects for eventual diplomacy:

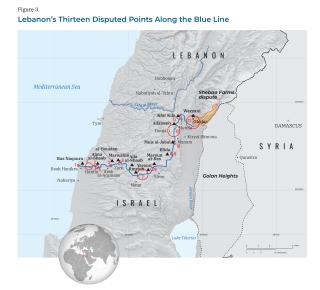

- Completion of a land border demarcation, for which most points are quite simple to resolve, including B1, separating Ras Naqoura (Lebanon) and Rosh Hanikra (Israel), where the United States has already proposed a compromise formula (see figure 3).

- Opening of the Ras Naqoura/Rosh Hanikra crossing to foreign tourist traffic.

- On Shebaa Farms and the Alawite village of Ghajar, admission by Lebanon that these areas were indeed parts of Syria when taken by Israel in the 1967 war, thus eliminating the pretext used for decades to foment tension with Israel.

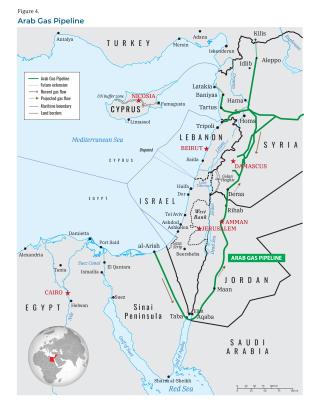

- Provision by Israel of natural gas to Lebanon via the Arab Gas Pipeline, through an extension from Syria, helping relieve Lebanon’s acute energy shortage (see figure 4).

- Joint water management for the Hasbani River and its tributaries, and coordination on sewage treatment in the basin to prevent pollution.

- Opening of Israeli and Lebanese airspace to civilian aviation, which would principally benefit Lebanon by shortening the flight time from Beirut to Saudi Arabia.

- Permission for supervised pilgrimage to holy places in the two countries. This could include, for example, making the tomb of Saint Charbel (in Annaya) and Khalwat al-Bayada (near Hasbaya) available to Israeli Christians and Druze, in return for making Jerusalem, Nazareth, and—depending on political and security circumstances—Bethlehem as well as Jethro’s tomb (west of Tiberias) available to Lebanese Christians and Druze.

Recommendations

Peace between Israel and Lebanon may still appear distant, but both Prime Minister Netanyahu and President Aoun have cracked the door open. For the first time in years, leaders on both sides are articulating the possibility of ending the state of war. This shift in public discourse provides an opportunity to build a dynamic that normalizes the idea of peace.

For the Trump administration, which envisions Lebanon as a future signatory of an expanded Abraham Accords, the moment is ripe to embrace the peace agenda and encourage Lebanese to view it as a way to avoid further war and salvage the country’s broken economy. Operationally, such a course would involve disconnecting peace diplomacy from implementation of the ceasefire—or, to be more precise, circumventing both the Hezbollah obstacle to disarmament and the potential of a renewed Israeli military operation by convincing the Lebanese government to begin its own peace process with Israel.

Specifically, pieces of this approach would include:

- Efforts by U.S. officials to enlist major regional allies—including Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar—to sign off on a Lebanese government decision to begin its own peace process with Israel. This would be untethered from progress on the Palestinian front.

- A stick-and-carrot U.S. policy to incentivize easing of Lebanon’s anti-normalization laws. On the one hand, this could include U.S. Department of State and Treasury sanctions on Lebanese judicial and law enforcement officials involved in enforcing these laws; on the other hand, it could include certain economic benefits that would come with easing of these laws.

- A larger package, including the benefits noted above, designed to address Lebanon’s desperate economy—which has shrunk by nearly 40 percent since 2019. This could encompass a plan to unlock international reconstruction aid, revive tourism, and restore investor confidence linked to incremental peacemaking steps with Israel, such as convening peace talks, demarcating borders, and establishing liaison offices.

- Contextual framing through a major communications and information effort that outlines the benefits of peace. This would include explaining how Lebanon would benefit from a free trade zone covering southern Lebanon and northern Israel, from tourists crossing the Israel-Lebanon border, and from the substantial investment that would flow into Lebanon in an era of peace.

- At the same time, reminding Lebanon that choosing neither to disarm Hezbollah north of the Litani nor to pursue peace diplomacy with Israel will come at a cost—losing U.S. aid to the Lebanese Armed Forces, losing U.S. backing of international support to Lebanon’s economy, and losing any U.S. effort to restrain Israel from completing Hezbollah’s disarmament “the hard way.” That stick should get the attention of Lebanon’s leaders.

To be sure, pursuing even incremental steps toward peace will be an uphill climb in a country long dominated by Iran’s chief regional proxy. But if Hezbollah is occupied with parrying the government’s disarmament efforts and if the Aoun-Salam governing duo can advance this project, an opening may exist to project to ordinary Lebanese the potential benefits that could come with taking the diplomatic path with Israel. In this regard, the U.S. role will be critical—to inject this initiative with drive and enthusiasm, to shield it from attack, and to reward local advocates with a protective and supportive embrace.