- Policy Analysis

- Fikra Forum

Don’t Be Deceived by Reported Electoral Turnout: Analyzing Iraq’s Elections by the Numbers

By comparing the outcome of Iraq's recent elections with the country's demographic trends, a clear difference emerges between the proportion of Iraqis whose votes are represented in the new parliament and the Iraqi population writ large.

The Iraqi parliamentary elections held on November 11, 2025 marked a pivotal turning point in the history of the post-2003 Iraqi state. At first glance, these elections reversed a trend of political disengagement; the number of parliamentary candidates increased significantly from previous elections (7,926 candidates competed for 329 parliamentary seats), alongside a massive increase in electoral spending estimated at billions of dollars and an increase in the voter participation rate that defied expectations. However, simply reading the total figures published by the Independent High Electoral Commission (IHEC) without delving into the underlying details can give false impressions and inaccurate conclusions about what Iraq’s latest elections mean for the political preferences of Iraqis.

Recalculating Voter Turnout

A closer analysis of the numbers demonstrates the large gap between Iraq’s adult population and those who ultimately cast ballots. Iraq’s 2025 elections relied solely on electronic voting, which required all Iraqis to obtain an electronic voter card in order to be eligible to vote. Approximately 7.8 million Iraqis of voting age did not obtain this card—either due to administrative and logistical failures or an unwillingness to participate.

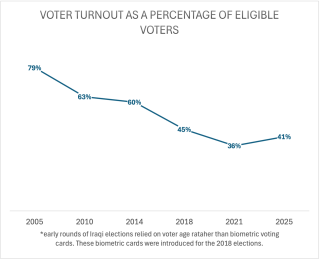

Thus, in spite of the increased turnout of "eligible voters" who possessed biometric cards, the 21.4 million voters in this election were paradoxically fewer than the over 22.1 million voters from the previous election in 2021. This decrease is all the more notable given significant population growth over the past four years, with over 4 million more Iraqis of voting age today. Accordingly, just 73% of Iraqi adults were "eligible voters" with biometric cards as compared to 88% in 2021. Thus, while the Iraqi High Electoral Commission announced a turnout rate of about 56% based on its definition of eligible voters, the electoral participation rate relative to the total number of Iraqis over 18 is just 41%.

Another sign of political pessimism is this year’s high number of invalid ballots. The 730,000 invalid ballots—6% of total votes cast—likely reflect not merely ballot errors but an intentional desire to boycott the elections by those who were apparently forced to go to the polling stations, especially in special voting that includes Iraqi armed forces, internally displaced Iraqis, and prisoners. When these invalid votes are removed, the participation rate of adult Iraqis drops further to 38.5%, close to the participation rate of previous elections that relied on biometric card voting.

However, even this number may have been inflated by two major events on election day that likely impacted voter behavior, especially in Baghdad and the south. The first event was the re-publication and promotion on social media of an old video of the representative of the Supreme Religious Authority in Najaf, Sheikh Abdul Mahdi al-Karbalai, casting his vote in the elections. Many believed that the video had been taken that day and interpreted it as a call from Iraq’s Shia Religious Authority to participate in the elections. The video garnered so much attention that it prompted a response from popular Shia leader Sayyid Muqtada al-Sadr who was boycotting the elections, stating that “We had hoped for better from you to save Iraq.” The impact of this video is suggested by the huge jump in voter numbers that occurred in the second half of election day. In some areas, especially in Baghdad and the southern regions of Maysan, Najaf, Dhi Qar, and Baghdad al-Rusafa, participation rates increased in the last six hours of election day by approximately 150%.

The second key variable was the astronomical increase in the number of election observers at polling stations, from several thousand during past elections to an estimated two million. These observers were paid workers, and their presence ensured two million votes in the ballot boxes given the expectation that they would vote in order to receive payment.

All these factors indicate that despite a higher reported turnout rate, Iraqis’ desire to participate has actually decreased, reflecting a more negative popular mood toward elections in particular and toward the democratic process in general—a view also clearly visible in trend data from 23 years of IIACSS public opinion polling.

Lost Votes and Imbalanced Sectarian Representation

The picture is further complicated by comparing the total number of votes obtained by parties that can be classified as Shia, Sunni, or Kurdish to rough estimates of their respective constituents in each governorate, district, and sub-district—calculated based on geographic population distributions recorded in the 2024 census and demographic information collected during IIACSS’ thousands of opinion polls. Members of parliament who can be classified as members of Shia parties collected 5.5 million votes and obtained 188 seats or 58% of parliament—eight seats fewer than in previous elections. As for parties and blocs that can be classified as Sunni, 2.75 million votes produced 77 seats (23% of parliament seats). Meanwhile, Kurdish parties gathered a total of 2.1 million votes, securing 54 seats (16% of total parliament seats).

Comparing these results to the estimated demographics of the country indicates marked differences in each group’s voting power. While every 29,000 Shia votes managed to secure one parliament seat, each Sunni seat needed 35,000 votes while it took 40,000 votes to secure one seat for Kurdish parties. These features suggest that the 45% of voters who were Shia determined the fate of 58% of total parliament seats, whereas the 55% of Sunni, Kurdish, and minority voters determined just 42% of parliament seats.

These disparities reflect the difference in participation rates in areas where each group holds a majority; participation rates were lowest in majority-Shia areas and higher in Kurdish and Sunni areas, thereby increasing the voter ‘price’ of each seat for the latter sects’ parties. This disparity may also reflect a discrepancy between the number of seats currently allocated to each governorate or within each governorate, based on previous population estimates, and the current demographic composition of Iraq. These findings suggest an urgent need to review the number of seats for each governorate compared to the recent 2025 population census.

Moreover, Iraq’s current voting law caused a significant portion of votes to be ‘lost’ to losing candidates. Winning Shia members of parliament obtained 1.89 million votes (versus an estimated 5.5-5.7 million Shia votes cast), while winning Sunni MPs obtained 960,000 votes (versus 2.65-2.85 million cast), and Kurdish MPs obtained approximately 1.1 million votes (versus 2.1-2.2 million cast). Collectively, Shia MPs represent only about 34% of total Shia voters and new Sunni MPs represent about 35%, whereas Kurdish MPs represent the will of about 50% of their respective voters.

Here again, and despite the higher reported participation rate, winning MPs received fewer total votes than the previous parliament—3,976,450 versus 4,066,000. This discrepancy highlights the differences between the previous law (the Single Non-Transferable Vote SNTV where each voter casts one vote for a candidate with more than one seat to be filled in each electoral district) and the current election law (proportional) where seats are distributed among candidates proportionally. The increase in "eligible voter" turnout did not translate into better voter representation in parliament, which is the fundamental goal behind any electoral process.

In fact, the large numbers of votes lost by some electoral blocs due to the new electoral law could have changed the electoral equation entirely. Only two blocs managed to exceed the one million vote threshold: Shia al-Sudani’s Reconstruction and Development bloc (1.3 million) and the Kurdistan Democratic Party (1.04 million). Yet these two entities were also some of the biggest losers of votes. The Reconstruction and Development bloc lost 734,000 votes, or 57% of its total voters, while the Kurdistan Democratic Party bloc lost 544,000 votes representing 52% of its total voters. The Sadiqoon bloc’s luck was no better, as 68% of its total votes were wasted, while Taqaddum lost 500,000 votes (54%) of its total votes.

Accounting for all these developments, the current parliament represents just one-third of those 21 million Iraqis who voted in the elections, or 13% of the total adult Iraqi population—a warning for politicians euphoric about the increased number of participants. Reflecting on the small percentage of voting-age Iraqis who are actually represented in the new parliament, parliamentarians will likely face an arduous task in convincing Iraqis that these elections brought them the best possible politicians.

Which Parties Benefited in the New Elections?

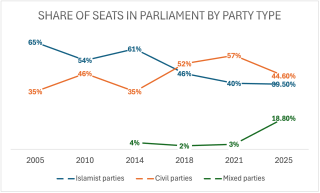

Both Iraqi political will and the new electoral system altered the composition of this new parliament significantly. Until recently, Islamist parties proved successful in the post-2003 elections relative to civil parties ("secular" would be something of a misnomer here due to their lack of an expressly secular character). Islamists formed about two-thirds of the first parliamentary session and 54% of the second parliamentary session, rising again to 61% of seats in the third session. Their power in the post-2003 period was such that some Iraqis accused the United States of a conspiracy to ‘Islamicize’ Iraq, demonstrating the major role that these parties were understood to have during this period.

Nevertheless, the Iraqi voter turned against Islamist movements in the 2018 session after holding them responsible for the failures Iraq had suffered since 2003, when civil parties came to form a simple majority in parliament (52%). Continued frustration with the political system later manifested in the 2019 Tishreeni Uprising. This trend continued in the 2021 elections, a Purple Coup against the ruling political class. Then, civil movements achieved unprecedented success by capturing 57% of parliament seats, while Islamist groups held just 40%. This shift occurred despite most civil parties boycotting the elections while all political Islamist groups (Shia, Sunni, and Kurdish) participated.

Yet this most recent election has altered this trend. Civil forces’ boycott of the 2025 elections via a large campaign led by Iraqi influencers and intellectuals, the failure of civil and Tishreeni representatives in the 2021 parliament, and the success of experienced Islamist parties in waging a campaign to demonize Tishreenis and its civil forces all led to non-Islamist parties losing their gains from the 2021 parliament, down from 57% to 44.6% in the upcoming parliament.

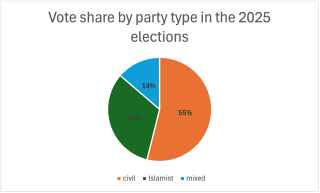

Yet the decline in civil forces’ influence did not result in a major increase for Islamist parties, who obtained just 39% of seats. Total votes likewise shrank; according to Election Commission figures, all Islamist groups in the elections collectively obtained about 3.5 million votes, or 33% of total votes (note Figure 3)—a slight decline from 34% in 2021. This reflects the extent of Islamist movements’ organization and ability to utilize their popular bases efficiently, even as their overall support declines. Moreover, the vast majority of Islamists still in parliament are Shia—the Sunni Islamist party did not participate while Kurdish Islamic parties obtained only five seats. Even so, Shia Islamists are likewise experiencing electoral losses over time, now representing only 66% of total seats allocated to Shias across Iraq. It is clear then that the non-Islamist loss was not translated into Islamists’ electoral gain in the 2025 elections—so what actually happened?

The phenomenon of mixed or unclear-identity parties and blocs—containing both politicians who call for religious and civil states—witnessed significant growth. They now account for 19% of seats after holding only 2-4% of seats in the three previous parliaments (2014, 2018, 2021). These movements generally lack a clear intellectual ideology and are built mostly on temporary electoral alliances between both types of politicians. The Reconstruction and Development bloc is perhaps the best example of this classification, which includes the Islamist Jund al-Imam party led by Ahmed al-Asadi and the secularist Wataniya alliance led by Allawi. These blocs represent an attractive mixture for Iraqis: civil or secular thought with firm and clear religious values.

However, political Islam’s overall influence on Iraqi politics has not decreased correspondingly. Political Islam, specifically on the Shia side, still controls the keys to government in all state institutions. There is no better evidence of this than that the Shia Coordination Framework, with more than two-thirds of its members falling into the Islamist category, since its bloc controls the choice of Prime Minister as well as the presidents of the republic and parliament.

Armed Groups’ Representation in the 2025 Parliament

Armed groups have likewise achieved a larger share of seats relative to their voter base in this latest parliament. Despite the Iraqi constitution explicitly stating in its ninth article a rejection of establishing armed groups outside the state’s scope, as well as a prohibition of members of armed forces from running in elections in general, armed group participation has been present since the beginning. Badr Forces and the Mahdi Army participated in the first Iraqi elections held in 2005 within the United Iraqi Alliance list, winning first place and forming the government.

The 2018 elections saw new armed groups (mostly Shia) entering into parliament after their contribution to fighting ISIS and the issuance of Popular Mobilization Law No. 40 of 2016, which allowed some to fall partially or fully under the umbrella of official Iraqi security forces. Consequently, two classifications emerged in Iraq for those groups. The first is their military classification according to their position within Iraqi state armed forces:

1. Merged armed groups fully integrated within the Popular Mobilization institution

2. Hybrid armed groups having armed forces inside the Mobilization system and armed wings outside state control

3. Independent armed groups not linked to the Iraqi state

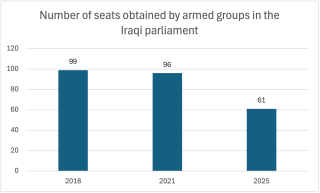

The second classification concerns these groups’ presence in Iraqi electoral politics or lack thereof. Hybrid groups are now represented in parliament, while other groups have by and large not yet entered the electoral arena. Figure 4 shows that parliamentary seats for armed groups in 2018 reached 99 seats (97 of them Shia) representing 30% of total parliament seats. In 2021, their number decreased to 96 seats (92 of them Shia) representing 29% of total parliament seats. This percentage decreased more significantly after the Sadrist Movement, which has an armed wing and won first place in previous elections with 73 parliamentary seats, withdrew from parliament. In the recent elections, armed groups’ seats decreased to 61 seats (56 of them Shia) or 18.5% of Iraq’s upcoming parliament, indicating that the relative weight of armed groups has shrunk considerably.

Yet despite the Sadrist movement’s boycott of these elections, the number of votes obtained by armed groups increased from about 1.4 million votes in 2021 (inclusive of votes for the Sadrist movement) to approximately 1.627 million votes in these elections, and the total seats controlled by the Badr Organization and Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq doubled from 17 seats in 2021 to 45 seats. The number of Kata’ib Hezbollah seats also increased from one to 6 seats in these elections, in addition to a new entry by the Imam Ali Brigades group led by Shibl al-Zaidi, which won 5 seats. It should also be noted that all armed factions with political arms inside the 2026 parliament are either directly or indirectly linked to Iran, increasing the size of Iranian influence inside the upcoming parliament.

The total votes obtained by armed groups in the 2025 elections exceeded 1.627 million votes overall, representing 16% of total valid votes, of which 450,000 votes obtained seats representing 11% of total votes of parliament winners. Yet if we take into account the actual participation rate in these elections as well as the boycott rate in southern areas to which those groups belong, it is clear that those groups attracted much less than 10% of total Shia voters. Nevertheless, the presence of these groups’ representatives in Iraq’s most important legislative institution and their doctrinal (and sometimes organizational) affiliations outside Iraq makes their political weight and influence on Iraq’s future much greater than their low popular support.

The increased participation rate in recent Iraqi elections should not be confused with Iraqi street satisfaction with the political and democratic process in Iraq. The increase in the abstention rate, abundance of invalid ballots, and political money pumped especially through wealthy parties’ employment of a huge number of election “observers” are all indicators of structural and functional defects in the Iraqi electoral process.

The large number of lost votes of those who did put in their ballot suggests a further issue. Though Iraqi election law is changed almost constantly for each election cycle, implementation of the current “proportional” law needs a serious review in terms of its method of calculating winning seats and number of electoral districts, since the previous law appears to have been closer to representing the Iraqi street and its various components. Here, recent population census data conducted in 2024 should be taken into account, as comparing its figures with the number of seats allocated to each governorate appears to seriously need review to ensure more just proportional representation.

These issues have impacted the composition of Iraq’s new parliament; election results reflect a clear failure by both civil and Islamist currents to gain Iraqi voter confidence, who appear more inclined toward non-ideological parties that combine explicit belief in Islam with a civil state. And despite the relative decrease in seat numbers and votes obtained by armed group representatives in Iraq indicating Iraqi voters’ limited interest (especially in southern Iraq), the potential political influence of these groups inside Iraqi parliament, and thus on the Iraqi government to be formed, appears greater this time around.

The upcoming government will undoubtedly face very difficult choices in how to maintain a delicate balance between satisfying those groups on one hand and satisfying the Iraqi street that generally rejects these groups on the other. Moreover, it will have to formulate a response to American, international, and even regional pressures to dissolve those groups and exclude them from the Iraqi political scene. In this regard specifically, the coming days will reveal the size of those groups’ political influence in the new government formation process and the extent of their influence in choosing the key leadership positions currently under discussion.