- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 4095

Syrian Citizenship for Foreign Fighters? U.S. Red Lines and Nuances

Any proposal for granting citizenship to such fighters must be careful, clear, and firm in how it addresses various complexities, including international concerns about external security threats, Syria’s stability, and the post-Assad accountability process.

A recent petition submitted to Syria’s interim government is seeking citizenship for foreign fighters who traveled there to take part in the civil war. While President Ahmed al-Sharaa hinted at taking this step for some foreign fighters earlier this year, it is unclear how (or even if) Damascus will answer the current petition, which many have dismissed given the manner in which it was raised (via social media) and the person who initiated it (Bilal Abdul Kareem, a U.S. citizen who is not associated with the factions that lead post-Assad Syria).

Whatever the veracity of the current proposal, it comes in the wake of months-long bilateral discussions on this exact issue. In March, the Trump administration gave the new government eight conditions for partial sanctions relief, including a demand that foreign fighters not be installed in senior roles. Damascus responded that this issue “requires a broader consultative session.” In May, the administration updated its conditions, urging Sharaa to “tell all foreign terrorists to leave.” In June, however, U.S. envoy Tom Barrack hinted at a U.S. “understanding” that incorporating some foreign fighters into the Syrian army would be okay if done transparently. Meanwhile, the administration quickly suspended most U.S. sanctions against Syria, signaling (perhaps inadvertently) that its conditions had been sufficiently met.

Why did the administration seemingly move from explicit prohibitions to tacit concessions on this complex issue in a matter of weeks? And should certain red lines really be crossed given the fragility of Syria’s transition and the well-documented role that foreign fighters have played in past human rights abuses and recent intercommunal massacres?

Differentiating Between Foreign Fighters

Broadly speaking, the foreign fighters who remain in Syria can be categorized in three large groups:

- Those associated with the terrorist-designated Islamic State (IS).

- Those associated with the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), a Kurdish group that is based primarily in Turkey but also operates in Syria, Iraq, and Iran. It is designated as a terrorist entity by the United States and others.

- Those associated with former Syrian opposition forces, including Sharaa’s formally defunct group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), which was removed from the U.S. list of Foreign Terrorist Organizations last month but remains designated by the UN.

The first category primarily consists of thousands of IS fighters and affiliated individuals held in northeastern detention facilities by the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). Both the Syrian government and much of the public disapprove of these fighters, blaming them for worsening the war and bringing more death and destruction to Syria. The U.S.-led coalition has repeatedly encouraged—though, importantly, not required—other countries to repatriate their IS-affiliated citizens. Yet this process has been slowed by the SDF’s nonstate status and the fact that many foreign governments have strong political, legal, and security concerns about voluntarily repatriating such individuals.

To be sure, none of these northeastern detainees would likely benefit from a decision to grant citizenship to foreign fighters. The same goes for the thousands of active IS fighters who remain at large and continue to operate against the new government, just as they did against both HTS and the Assad regime during the war. Yet some IS-affiliated individuals were freed from regime prisons after Assad’s fall and may seek to exploit any new citizenship laws, whether for their own benefit or in aid of active fighters.

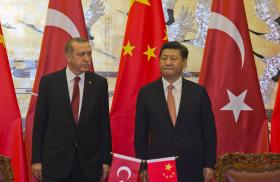

The second category of foreign fighters comprises those associated with the PKK, which includes mostly non-Syrian Kurds based in the northeastern areas controlled by the SDF. Turkey contends that the PKK’s presence in Syria is a threat and has launched several incursions into the northeast over the years.

Here, too, none of the fighters in this category are likely to be included in any new citizenship laws. Given the PKK’s history and Turkey’s influence on Damascus, many Syrians view the status of these fighters as a Turkey-PKK issue and oppose granting them citizenship. In an effort to differentiate between his forces and the PKK, SDF leader Gen. Mazloum Abdi has previously stated that PKK foreign fighters would leave Syria under the right conditions. In short, the status of these fighters, while highly contentious, will likely be resolved through discussions between the SDF and Damascus.

That leaves members of the third category as the most likely to benefit from a future citizenship law. Given their participation in the offensive that toppled the regime and their association with former opposition forces like HTS, these foreign fighters enjoyed broad support across Syria in the early days of the post-Assad transition. Moreover, the country’s interim leaders have contended that these fighters are very loyal to the new government, and that keeping them within the state system would be safer than abandoning them. Yet complications abound:

- In some cases, foreign fighters aligned with Sharaa’s government have taken part in the growing wave of intercommunal violence that Damascus is struggling to contain, spurring the public to question their role in the country’s future.

- Many of these fighters were once associated with terrorist groups like IS and al-Qaeda (though they are now helping Damascus fight such groups).

- For some foreign fighters, international law would not support them being forcibly returned to their countries of origin due to human rights concerns (e.g., Uyghur fighters would face death sentences if they went back to China).

- Despite HTS formally disbanding and the United States asking others to delist the group, it is still on the UN terrorist list, which could complicate matters for Syria in the international arena.

Policy Recommendations

Implementing any citizenship proposal related to foreign fighters raises big questions for both U.S. policy and the future stability of Syria. Washington and Damascus should therefore be crystal clear on the red lines and plans for this process.

First, they should continue taking steps to reaffirm their shared view that granting citizenship to IS-affiliated individuals is a nonstarter. Both governments are actively working to counter IS, with Damascus using actionable U.S. intelligence to fight the group’s persistent insurgency. The Trump administration should not only continue this cooperation, but also support ongoing discussions between Damascus and the SDF regarding eventual responsibility for the detention facilities. Yet Washington should not rush this process given its significant security concerns, its years-long training and equipping of the SDF for this mission, and the lack of sufficient assurances that Damascus has the will, capabilities, and resources to fully assume this mission at present. The administration should also keep pressing other countries to repatriate these individuals, reminding them that once the Syrian government moves past its interim status, it could use its authority to unilaterally deport such detainees, removing the option of conveniently deferring the repatriation issue.

Second, U.S. officials should press Syrian and SDF officials to come to the table for intensive discussions on the fate of non-Syrian Kurdish fighters in the northeast. With negotiations seemingly stalled since March, Washington should remind both parties that continued U.S. support rests on them working toward national stability. Removing foreign fighters associated with the PKK would not only alleviate Turkey’s main concern, but also help lift some of the barriers to reconciliation between Damascus and the SDF. This in turn could serve the Trump administration’s broader goal of lightening the U.S. footprint in the Middle East, a key prerequisite of which is stabilizing Syria’s northern and eastern frontiers.

Third, Washington and its partners need to carefully engage with Damascus on the topic of granting citizenship to foreign fighters associated with former opposition forces, since this could have numerous implications for Syria domestically and internationally. President Sharaa appears ready to take on the responsibility for these individuals, but the United States will need specific, serious assurances on this front before supporting such a measure. This includes candid conversations about the following:

- Barring foreign fighters from leadership and decisionmaking roles in the security services. Given the background of these fighters, the U.S. government needs to clarify its red line: namely, it is unacceptable for such individuals to hold the types of security roles that would compromise U.S. support and intelligence-sharing efforts.

- Accounting for the potential impact on Syrian recovery and accountability. As noted above, some of the fighters in question have been implicated in recent massacres and other abuses, so it is unclear how various segments of the public would react to granting them citizenship, let alone roles in the security forces. Either move could potentially impede recovery and stabilization efforts. Moreover, the notion of providing government jobs and services to non-Syrians may prove divisive, since inclusivity, accountability, and limited domestic resources are currently dominating the national discourse.

- Providing international security guarantees. Even if Damascus bars naturalized foreign fighters from certain security services and roles, it would still need to spell out what steps it will take, such as continued monitoring, to ensure that these former fighters do not pose a threat beyond Syria’s borders.

- Addressing diplomatic concerns. Some foreign governments may be relieved if they no longer have to deal with the question of what to do about nationals who went off to join the Syrian jihad. Others, however, will have political or security concerns about Damascus unilaterally granting citizenship to such individuals, and they may alter their future diplomatic engagement with Syria accordingly. For example, Lebanon recently objected after discovering that Syria’s new head of security for the western border province of Homs is a former Lebanese army officer—a revelation that exacerbated growing bilateral distrust over various issues on their shared frontier. As Syria works to reenter the international community, Washington should encourage it to clearly articulate any naturalization effort for such fighters.

In sum, as Damascus weighs the possibility of granting citizenship to certain foreign fighters, the United States must clarify its red lines, emphasize the implications that such a decision would have for Syria domestically and internationally, and reinforce the need for a clearly communicated and transparent process.

Devorah Margolin is the Blumenstein-Rosenbloom Senior Fellow at The Washington Institute and an adjunct professor at Georgetown University.