- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 4139

A More Effective Approach to Countering the Muslim Brotherhood

Instead of pinning a terrorist designation on the entire group, the Trump administration should focus more narrowly on the national security threats presented by individual Brotherhood branches and organizations, especially those funding Hamas.

On June 1, an Egyptian national carried out an antisemitic firebombing attack targeting a group of peaceful Jewish protesters in Boulder, Colorado. Social media posts indicated the accused attacker supported the Muslim Brotherhood, prompting lawmakers in Washington to call for the group’s designation as a terrorist group—something that has been squarely on the Trump administration’s radar since early in its first term. The issue has now gained legislative momentum, with bills in the U.S. House and Senate that would require the administration to take this step.

Movement with No Unitary Leadership

Despite recent momentum, designating the entire Muslim Brotherhood movement as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) has proven challenging. While the Brotherhood has spawned branches around the world since its creation in Egypt in 1928, including most notably Hamas, it does not operate as a centrally directed, unified organization. In August, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio said that while the Brotherhood represents a “grave concern,” the FTO designation process has been stymied by the legal requirement that the U.S. government make its case and “show [its] work” to a court. (Some advocates of a broad designation have noted that other governments, including the United Arab Emirates, Jordan, and Egypt, have taken this step, but the United States has—and should uphold—higher legal thresholds and more rigorous internal reviews.)

The president could theoretically target the Muslim Brotherhood in a new, standalone executive order, but the U.S. administration clearly seems to want to act under existing counterterrorism authorities to underscore the dangers of the Brotherhood. Adding the group to a legacy designation authority targeting the Palestine Liberation Organization, as the Senate bill proposes, runs up against the reality that the PLO has a centrally run leadership, whereas the Muslim Brotherhood does not.

A legal and productive first step would be to list as Specially Designated Global Terrorists (SDGTs) those Brotherhood-associated entities that have provided funds or other material support to Hamas—activity that has increased dramatically since the group’s October 7, 2023, terrorist assault on Israel. The administration could also sanction as FTOs those few Brotherhood branches that do engage in terrorism, following President Trump’s practice in his first term. More branches would likely qualify for designation today.

Terrorism-Funding Brotherhood Entities as SDGTs

The Trump administration should look closely at any Brotherhood-affiliated entities that have provided support to Hamas, which is illegal under U.S. law. Such a focus is long overdue. In a 2015 report, the UK government accused the Muslim Brotherhood of “deliberately, wittingly and openly” incubating and sustaining Hamas, including facilitating its funding. The report also underscored the ongoing linkages among Hamas and Brotherhood branches and organizations throughout the Middle East.

Such ties are even more blatant since Hamas’s October 7 attack. In a September 2024 report, the Israeli government explained that Hamas has established a “network of activists and organizations” in Western Europe, many of which are tied to the Muslim Brotherhood. Indeed, the Hamas-Israel war has provided a treasure trove of information about various groups’ sanctionable activity.

Material Israel has collected from Hamas tunnels and offices in Gaza will likely identify many culprits to choose from. For example, Israel announced several months ago that documents found in Gaza showed direct ties between Hamas and the Popular Conference for Palestinians Abroad (PCPA), which Israel designated for ties to Hamas and described as a Brotherhood-linked organization. According to Israel, the PCPA “functions as Hamas’ representative abroad, operating de facto as Hamas embassies.” Jordanian authorities have noted a similar trend among Brotherhood-affiliated organizations in the kingdom. After banning the Brotherhood in April, the Jordanian government followed up in July with legal action against in-country NGOs tied to the movement.

Ties That Bind: Hamas and the Brotherhood

Hamas and the Muslim Brotherhood have been intertwined since Hamas’s establishment, when the group’s 1988 charter defined it as the movement’s Palestinian branch. Thereafter, Brotherhood outposts around the world—including in the United States—created entities to support the militant Palestinian branch. Still in 1988, the head of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Palestine Committee traveled from the Middle East to meet with movement leaders in the United States and created the Holy Land Foundation for Relief and Development (HLF) as the primary U.S.-based vehicle to raise financial and other support for Hamas. The U.S. Department of the Treasury designated the HLF for its ties to Hamas in 2001, and a U.S. court convicted its leaders in 2008 for providing millions of dollars in support to the group. In 2011, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit reaffirmed this verdict, pointing to evidence that after Hamas’s formation, “the Muslim Brotherhood directed its world-wide chapters to establish so-called ‘Palestine Committees’ to support Hamas from abroad.”

Muslim Brotherhood members followed this playbook elsewhere around the world as well. In 2000, at the start of the second Palestinian intifada, Hamas leaders established the Union of Good, a global umbrella organization, to facilitate Hamas’s overseas financial activities. This network, which included more than fifty so-called charities, was led for many years by the influential Brotherhood spiritual leader Yusuf al-Qaradawi. The U.S. Treasury Department subsequently designated both the Union of Good and many of its members for their ties to Hamas. In its designation earlier this year of a Netherlands-based NGO, the Treasury Department confirmed that the Union of Good is still very much in operation and reports “directly to the Hamas military wing.”

Evidence from other cases abounds:

- In 2010, Germany banned the German wing of the Turkish group Internationale Humanitaere Hilfsorganisation (IHH)—a member of the Union of Good—citing the group’s fundraising for Hamas. Israel had banned the group—which it describes as “being close to the Muslim Brotherhood”—in 2008 for ties to Hamas and deported an IHH activist from the West Bank for transferring funds to Hamas-controlled organizations in Hebron and Nablus.

- In a 2019 criminal case, a Spanish court pointed to another Muslim Brotherhood–dominated umbrella organization, the Federation of Islamic Organizations in Europe, for its ties to Hamas. The court found that in some European countries, the federation was seen to have “strong links with Hamas and with other organizations that have supported Hamas.”

- In June 2025, the Treasury Department designated what it described as “sham charities”—several of which appear to be tied to the Brotherhood—for funding Hamas. These groups’ reach is broad: the designated entities have been located across the Middle East, Africa, and Europe, including in Algeria, Lebanon, the Netherlands, Qatar, Sudan, Turkey, and Yemen.

Violent Brotherhood Branches as FTOs

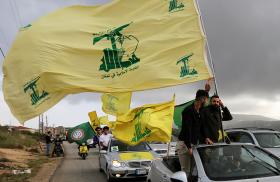

In addition, several more Muslim Brotherhood branches could potentially be designated based on their violent activities. For example, when Jordan banned the movement’s branch in April, the action followed charges against a number of its members for organizing and planning a terrorist attack. Another example is the Lebanese Brotherhood branch, al-Jamaa al-Islamiyah, and its militant wing, the al-Fajr Forces. This branch has launched rocket attacks targeting Israel in coordination with Hezbollah, and has also worked closely with Hamas in Lebanon.

Yet many other Brotherhood branches have long been careful to avoid violence, recognizing that crossing such a line would open them up to more government scrutiny and punishment. Designating Brotherhood branches that have engaged in terrorist violence could warn others away from that threshold.

Officials in the first Trump administration encountered evidentiary challenges and settled for designating two Egypt-based Muslim Brotherhood splinter groups—Liwa al-Thawra and Harakat Sawad Misr—that helped launch a series of deadly bombings, assassinations, and other attacks in Egypt over the period 2015–17. The second Trump administration should follow this focused, circumspect approach.

Conclusion

The evidence validates U.S. concerns about the Muslim Brotherhood, particularly as the Trump administration aims to move beyond the Gaza ceasefire to build a more stable, peaceful Middle East. But taking sweeping action against the entire group will be both counterproductive and ineffective. Instead, the administration should look closely at Brotherhood entities that provide financial support for Hamas as potential SDGT targets. It should also designate those branches that are tied to violence as FTOs. At the same time, it should provide a strong legal framework to go after Brotherhood organizations using both sanctions and law enforcement tools.

On the Hamas financing front, authorities should first zero in on entities falling under the Union of Good, Federation of Islamic Organizations in Europe, and Popular Conference for Palestinians Abroad. The impact of unilateral U.S. sanctions will only go so far on their own, and other key governments—particularly in Europe—will be far more likely to take similar steps if they are persuaded that the U.S. actions are legally sound and based on concrete, reliable information.

Michael Jacobson is a senior fellow in The Washington Institute’s Reinhard Program on Counterterrorism and Intelligence and former director of strategy, plans, and initiatives in the State Department’s Counterterrorism Bureau. Matthew Levitt is the Institute’s Fromer-Wexler Senior Fellow, director of the Reinhard Program, and a former Treasury Department deputy assistant secretary for intelligence and analysis.