- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 4116

How Renewed Oil Flows from the ITP Could Benefit U.S.-Iraq-Turkey Relations

The potential economic and strategic benefits of reopening the northern Iraqi pipeline are clear, but the agreement still faces bureaucratic, political, and security challenges before exports can resume in earnest.

After a halt of more than two years, crude oil flows from the Kurdistan Region of Iraq to Turkey’s Ceyhan export terminal have resumed. The reopening of the Iraq-Turkey Pipeline (ITP) late last month followed a long-awaited U.S.-facilitated deal between the federal government in Baghdad, Kurdish leaders in Erbil, and international oil companies (IOCs) operating in the Kurdish region. The restart also coincided with a September 25 White House meeting at which President Trump asked President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to stop importing discounted Russian oil.

Multiple factors are at play behind these announcements, including complex intra-Iraqi politics, Erdogan’s desire to curry favor with the United States, and Washington’s desire to use oil exports as a lever on Moscow while simultaneously improving Iraq’s commercial environment for American companies. If the Trump administration keeps pressuring Turkey to reduce Russian barrels, questions will arise about possible crude oil alternatives of similar “medium sour” quality, and supplies from northern Iraq—which will now be exclusively marketed by the country’s federal oil organization under a new commercial process—will be considered as one of these alternatives.

Of course, the Trump administration must be clear-eyed about the unlikelihood that Turkey will completely quit Russian oil, and about the minimal impact that these developments can have on Russia’s overall global oil sales given the relatively small amounts of crude involved. Yet the possibilities are still promising if ongoing negotiations are handled well—not only for Turkish refiners who may need to diversify their crude oil sources in the future, but also for wider relations between Iraq, Turkey, and the United States.

The Turkish Angle

Relations with Russia. Turkey is a significant buyer of Russian oil and is expected to remain so, but scaling back these purchases may be achievable. For one thing, crude from northern Iraq is similar in quality to Russian oil (namely, Russian Urals crude grade). And although Russian crude is cheaper, Ankara may see Iraqi supplies as a useful way to diversify its oil imports amid tightened European sanctions on Russian supplies—and, by extension, lessen its broader reliance on Moscow in the energy and economic sectors. To further such goals, Washington needs to continue facilitating negotiations between Baghdad and Erbil so that crude flows from northern Iraq are sustained to a degree that encourages increased exports from fields in the Kurdish region as well as those under federal control in Kirkuk, depending on domestic market conditions.

Relations with Iraq. In recent years, anticipating a U.S. military drawdown in Iraq and abhorring the idea of a power vacuum there, Turkey has sought to help with the country’s re-centralization. Ankara’s resultant strategy for Iraq is rather straightforward: promoting Turkish money over Iranian guns and influence. To this end, it has proposed the “Development Road,” a network of highways, rail lines, and pipelines stretching across Iraq and Turkey and connecting Asian and European markets via the Indian Ocean and Mediterranean Sea. The reopening of the ITP is the first concrete outcome of this proposal.

Relations with the United States. Ankara has been aggressively courting Washington of late, in large part to secure the purchase of coveted F-35 fighter jets. After Turkey purchased S-400 missile defense systems from Russia in 2017, it faced U.S. congressional sanctions blocking military sales, including the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) and the 2020 National Defense Authorization Act. Yet President Trump believes that Turkey is a sufficiently important ally in great power competition to warrant resetting the military relationship and allowing weapons sales to proceed. To this end, he will likely issue a national security waiver bypassing CAATSA in the coming months and lean on congressional allies in the midterm to eliminate the NDAA wording banning military sales to Turkey.

In return, the administration will expect confidence-building measures from Ankara, and this is where the ITP comes in (among other measures). For a bevy of strategic, political, and economic reasons, Turkey is highly unlikely to immediately cut off all of its oil purchases from Russia, but re-flowing Iraqi oil into global markets would be a substantial goodwill measure toward Washington and Baghdad, even if the amounts in question are small compared to overall Russian exports. Erdogan also told Trump during their meeting that Turkey would commit to buying more U.S. liquefied natural gas (LNG), boosting both Trump’s agenda of “selling American” and Ankara’s effort to ease its dependence on Russian energy imports (since it also buys significant amounts of Russian gas). Taken together, these moves bring Turkey closer to acquiring F-35s than before.

Details of the Iraq Deal

The interim ITP agreement will help kickstart negotiations to resolve longstanding political, technical, and administrative problems between Erbil and Baghdad related to oil production and exports from northern Iraq. It also paves the way for discussions between the Kurdistan Region and IOCs regarding the more than $1 billion in arrears that Erbil owes them.

According to an industry source familiar with the talks, the initial deal calls for a three-month period to enable crude exports to restart. As oil flows resume, an independent Western consulting company will carry out required assessments to calculate the true costs of production and transportation in the Kurdistan Region and address payments to the IOCs. After December 31, the deal will be subject to monthly renewal.

Currently, Kurdistan’s crude is produced from fields operated by eight IOCs. These include the American companies WesternZagros, Hunt Oil, and HKN Energy, which together represented more than $5 billion in northern Iraqi investments as of 2023. Under the new deal, around 180,000–190,000 barrels per day (b/d) of Kurdish crude are initially expected to be delivered to the State Oil Marketing Organization of Iraq (SOMO), which will now be the sole authority in control of the marketing process.

Notably, oil flows are not expected to return to their pre-2023 levels, at least for now. The ITP was shut down in March of that year after an international arbitration court ruled in favor of Baghdad, ordering Ankara to pay Iraq around $1.5 billion in damages for allowing Erbil to export crude oil without the federal government’s permission—a practice that had violated a 1973 treaty governing the pipeline. Previously, the ITP was transporting around 400,000 b/d of crude. Toward the end of March 2023, Kurdish oil was no longer exported to global markets, and production capacity gradually dropped. Yet some of the region’s oil was still being refined and sold domestically despite the pipeline closure. There were also reports that substantial amounts of Kurdish oil were being smuggled to Iran and Turkey via trucks.

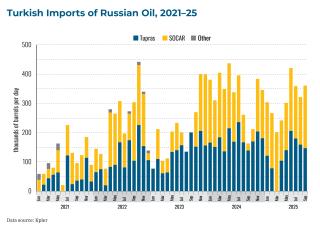

How ITP Flows Compare to Turkey’s Imports from Russia

Prior to the ITP’s 2023 closure, Italy, Greece, Israel, Croatia, and Turkey were among the main destinations for crude from northern Iraq, according to data from Kpler. Within the next few months, major Turkish refineries may have good reason to resume their purchases of restored Iraqi crude flows. Currently, they export oil products made from Russian crude to European markets, but this practice could become trickier amid new European sanctions.

In July, the EU banned the import of products derived from Russian crude starting in 2026, which oil industry sources agree will likely cause a shift in Turkey’s crude imports. If Turkish refiners decide they must obtain similar crude from elsewhere, northern Iraq could be one of the “best alternatives,” according to senior Kpler analyst Homayoun Falakshahi. Yet these refiners will have more than one option to choose from, and varying market prices could affect their decision.

During the first nine months of this year, Turkish refiners imported an average of 309,000 b/d of Russian crude. Most of these barrels were imported by refiner Tupras and Azerbaijan’s SOCAR, which controls the STAR Refinery in Turkey.

U.S. Policy Implications

The new ITP agreement still faces several challenges before exports can resume in earnest, including unresolved budgetary and administrative issues and the need for an overarching mechanism to guide oil production and exports from northern Iraq. Security challenges abound, too. Earlier this year, drone attacks against oil fields in the Kurdistan Region—purportedly by Iran-aligned militias—forced some facilities to suspend operations.

Yet these challenges are worth surmounting given the deal’s potential benefits for Iraqis—and for Americans, since U.S. firms operate the fields in question. Resuming flows from the ITP could also give Washington another lever (albeit a small one) against Russia, by peeling away a significant buyer like Turkey and improving relations between the two NATO allies. Officials should also bear in mind that supporting political stability and security in Iraq, OPEC’s second-largest oil producer, is critical for ensuring that the country’s oil supply to global markets is stable, particularly amid uncertainties about supplies from sanctioned market players like Russia. This applies to crude not just from the Kurdistan Region, but also from southern Iraq.

Moreover, given that Iran remains the most influential country in Iraq, supporting deeper Turkish economic ties with Baghdad is in America’s interest, starting with reopening the ITP. Having Ankara as a balancing economic power against Tehran would be a net positive for U.S. policy in Iraq.

Considering these interests, the Trump administration should maintain its diplomatic role in the pipeline negotiations to ensure the deal does not falter. Successive U.S. administrations have played a key part in urging Baghdad and Erbil to engage in constructive dialogue on resolving a crisis that has lasted over two years now, and on addressing other issues such as salary transfers from the federal government to the Kurdistan Region. Sustaining this momentum is essential, particularly if Washington wants to support a stable environment for U.S. companies who are already invested there and who aim to expand their projects throughout the country.

Noam Raydan is a senior fellow at The Washington Institute and co-creator of its Maritime Spotlight platform. Soner Cagaptay is the Institute’s Beyer Family Senior Fellow, director of its Turkish Research Program, and author of “Building on Momentum in U.S.-Turkey Relations.”