- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 4136

Houthi Maritime Threats and the Gaza Truce: Why Disrupting Supply Chains Is Indispensable

Despite the recent (and likely temporary) pause in ship attacks, various factors point to an enduring threat that will not dissipate until wider action is taken against the group’s far-reaching procurement networks.

Although the Yemeni Houthis have not launched further ship attacks since late September, freedom of navigation in the Red Sea and adjoining waterways is still under threat, and the new Gaza truce cannot be relied on as a guarantee that the group’s long maritime campaign is over. Earlier this month, a senior Houthi official declared that shipping attacks and other strikes would resume if “the [Israeli] enemy” takes further military action in Gaza. More tellingly, the maritime industry and coalition naval forces remain cautious, similar to their reaction during the short-lived Gaza ceasefire in January. The Houthi threat also continues to loom over Gulf countries and their economic interests, mainly Saudi Arabia, where the group targeted an oil tanker off the port of Yanbu on August 31 (see below).

In light of these ongoing threats, potential efforts to disrupt Houthi supply chains could prove crucial. In September, a tanker reportedly transporting Iranian liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) to the group was mysteriously attacked off the Houthi-controlled port of Ras Issa, leading one official to claim that Israel was responsible. As the U.S. Treasury Department intensifies its efforts to dismantle the Iranian networks responsible for illicit energy transfers to the group, Washington should keep a close eye on wider Houthi supply chains and procurement networks, since the risks to commercial shipping will not disappear so long as these networks remain robust.

Some Red Sea Access, but for Whom?

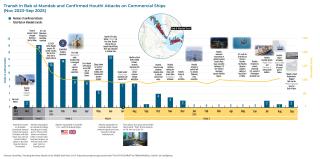

It has been almost two years since the Houthis set off their campaign against freedom of navigation in the Red Sea on November 19, 2023. Overall vessel transits via the narrow Bab al-Mandab Strait remain below their early 2023 levels, though some shippers returned to that route earlier this year in what industry sources attribute to “risk normalization.”

To better understand this trend, one can look to the example of crude oil exports from southern Iraq through the Suez Canal, particularly to Europe. According to the trade data firm Kpler, the volume of Iraqi Basra crude transported via that route climbed to around 320,000 barrels per day in July—the highest volume since December 2023, when several companies decided to avoid the Red Sea (at the time, the rate was about 609,000 b/d). This shows that some shippers kept using the Bab al-Mandab chokepoint despite Houthi attacks against two bulk carriers in July. The majority of that month’s Iraqi shipments via the Suez were carried by tankers owned or operated by Greek companies such as Dynacom and Polembros. Not all Greek companies are willing to navigate the southern Red Sea, however. Some have felt compelled to take the much longer route around the Cape of Good Hope instead, especially those with a history of trading at Israeli ports. In 2024, for instance, the Houthis attacked three vessels linked to the Greek firm Delta Tankers (for more on these and other incidents, see The Washington Institute’s maritime attack tracker.)

The same goes for commercial vessels with links to the United States and United Kingdom. Although the Houthis stopped attacking American vessels after the Trump administration halted its Yemen bombing campaign in May, data shows that U.S.-flagged vessels—particularly those owned or operated by giant companies like Maersk—are still avoiding the Red Sea. For example, the U.S.-flagged container ship Maersk Chicago (IMO identification number 9332975) sailed around Africa to get from Morocco’s Tanger Med port to Salalah, Oman, a voyage that lasted from September 15 to October 11 (see map below). If the ship—which was sailing at a speed that ranged between 15 and 18 knots—had taken the Suez Canal route instead, it would have reached Oman in about ten to twelve days.

In contrast, tracking done by the author shows that vessels linked to Russia and China remain among the most prolific users of the southern Red Sea. For instance, the waterway has been vital to transport Russian oil to Indian refiners amid intensifying U.S. and European sanctions. In September alone, India imported around 1.43 million b/d of Russian crude via the Suez; the Red Sea will presumably remain a key route for those Indian refiners who continue buying discounted supplies from Moscow.

Meanwhile, underwriters were offering lower prices on war risk rates (i.e., additional premiums on ships in high-risk areas) for Chinese owners compared to European owners, mainly due to the fact that China-linked vessels are less likely to be attacked by the Houthis. Indeed, ships tied to Russia and China continue to transmit messages via their Automatic Identification Systems clarifying their ownership and type of cargo—a clear signal to the Houthis not to attack them. These include sanctioned vessels such as the tanker Rigel (IMO 9296406), which is involved in the Russian oil trade and makes a point of signaling its Chinese crew and owner (see image below).

Saudi Attack Shift and Supply Chain Disruption?

In their most recent maritime attack, the Houthis targeted the Netherlands-flagged cargo ship Minervagracht (IMO 9571521) in the Gulf of Aden on September 29 despite the vessel having no known Israeli affiliation—an incident that came as little surprise given the group’s track record of launching attacks based on outdated or incorrect data (see The Washington Institute’s maritime attack tracker). Yet two other recent sets of incidents are worth examining further—one that highlights the long-term regional threat posed by the Houthis, and another that shows how the group continues to procure oil products despite sanctions and military strikes.

Saudi attacks. On August 31, the Houthis targeted the oil/chemical tanker Scarlet Ray (IMO 9799654)—owned by Israeli businessman Idan Ofer’s Eastern Pacific Shipping—around forty nautical miles southwest of Yanbu, outside their usual zone of operations for ship attacks. Although the vessel was not damaged, the incident showed the group’s ability to keep threatening Saudi Arabia by aiming near key energy and trade infrastructure, potentially signaling a shift in strategy compared to previous Saudi-linked attacks. In June 2024, for example, an explosion was reported a short distance from a merchant vessel off the Saudi coast near al-Shuqaiq, far south of Yanbu. Attacks close to Yanbu are particularly worrisome because it is one of Saudi Arabia’s major western ports for exporting oil, shipping an estimated 973,000 b/d in September according to Kpler.

More broadly, the Red Sea is key to the logistical ambitions laid out in Riyadh’s Vision 2030 plan. In early 2024, the kingdom launched its first independent feeder and short-sea shipping operator, Folk Maritime, which has been expanding its regional services since then despite the high risks in the Red Sea. Riyadh knows that its goal of becoming a regional logistics hub requires safeguarding freedom of navigation. As such, it hosted a conference in September with the UK to launch the Yemen Maritime Security Partnership, which aims to “enhance security in critical maritime waterways.” In response, the Houthi leadership was quick to portray the joint initiative as an effort to protect Israeli ships, indicating that the kingdom’s maritime security efforts will require a very delicate balancing act with the group to avoid direct confrontation.

Supply chain strikes? In mid-September, reports emerged that the Clipper (IMO 9102198), a U.S.-sanctioned ship carrying Iranian LPG, had caught fire while anchored at the Houthi-held port of Ras Issa. The source of the fire remains unclear, but its crew (mostly Pakistani) stated that the vessel was hit with a drone. One official accused Israel of attacking the ship, but this has not been confirmed by independent sources.

A few weeks later, the LPG tanker Falcon (IMO 9014432) experienced a blast in the Gulf of Aden. One initial report cited an “unknown projectile,” but an accident could not be ruled out according to United Kingdom Maritime Trade Operations (UKMTO). Similar to the Clipper, the Falcon was carrying gas loaded in Iran, raising questions about whether it was covertly attacked in an attempt to directly disrupt Tehran’s supply networks to the Houthis.

No Solution Without Disrupting Networks

Today, there is little mystery about if or when transit rates in the southern Red Sea will return to their early 2023 levels—it is now clear which shippers are willing (or unwilling) to take the risk in an area where danger has become normalized. As long as the Gaza and Lebanon fronts remain unstable, so will conditions in the Red Sea, since the Houthis have been clear about their willingness to take armed action in support of Hamas and, to a lesser degree, Hezbollah.

Given that the Houthis continue to have the upper hand in the Red Sea, Washington and its partners should focus on a long-term strategy to strengthen intelligence cooperation, particularly regarding the group’s supply chains and procurement networks. This means identifying ways to gradually disrupt these networks and test the limits of Houthi retaliation without further affecting regional trade.

Direct military strikes are not always effective in this regard. For example, despite heavy U.S. strikes this April against Ras Issa—a key location for importing oil products—ship tracking data shows that the Houthis were able to resume operations there. Individual ship sanctions are not a cure-all either. As the September Clipper incident shows, sanctioned vessels continued delivering supplies to Houthi ports.

This year, the Treasury Department increased U.S. sanctions against the Houthi revenue and procurement networks that have been central to financing the group’s weapons supply chains and maritime campaign. In the long run, efforts to resolve the Red Sea shipping threat—and meet the wider U.S. commitment to Middle East security—cannot succeed until Washington and its partners invest in fully mapping and understanding how Houthi procurement networks operate. This includes tracing activities that extend to Iran, China, and other locales, while also demonstrating a willingness to disrupt them effectively—beyond individual sanctions that the Houthis have already proven they can circumvent.

Noam Raydan is a senior fellow at The Washington Institute and co-creator of its Maritime Spotlight platform.