- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 4064

Back to the Table? Recommendations for Negotiations with Iran

A compilation of views on the next round of prospective talks with Iran, sanctions relief options, military and technical considerations, the international role, and more.

Now that an Iran-Israel ceasefire is in place, various players are setting the stage for what comes next, with U.S. officials mentioning the possible resumption of nuclear talks in a matter of days, Iranian leaders focused on publicly declaring victory, and observers worldwide debating the military and technical results of the fighting. What did the United States and Israel accomplish in terms of setting back Tehran’s nuclear and missile programs, and what should officials prioritize in the next round of diplomacy to secure and expand on these achievements?

U.S. Objectives

Dennis Ross

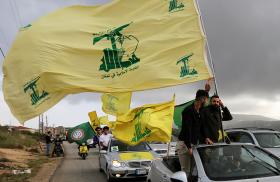

Good statecraft always depends on marrying objectives and means. While done all too rarely, smart statecraft is also guided by a sense of timing and knowing how to seize the moment. There is surely an opportunity to be seized now in a Middle East where the balance of power has been transformed; where the Iranian proxy network that controlled some states, paralyzed others, and coerced many of America’s friends has been decimated; and where Iran itself has been dramatically weakened and wants a respite and sanctions relief. For all of Tehran’s threats about what would happen if the United States attacked, the regime’s actual response to the U.S. strike was telegraphed, symbolic, and designed to avoid escalating to war with the United States. Much like after the 2020 killing of Iranian general Qassem Soleimani, the bluster was followed by a military response that was limited and designed to be a one-off.

At minimum, the United States should take advantage of the profound damage to Iran’s nuclear and missile infrastructure by pushing for a diplomatic agreement on the future of both. President Trump’s conclusion that the nuclear program has been set back decades could prove to be right, but that forecast currently depends on unilateral Iranian decisions. Yes, it would be extremely risky for Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and his regime to try reconstituting the nuclear and missile programs. Yet rather than simply hoping Tehran will heed that risk on its own, Washington would be far better off working toward agreements with intrusive monitoring and clear understandings about the consequences of violations.

President Trump has the leverage to achieve such agreements, provided he stays focused on the issue and does not leave the future of these programs up to Tehran or others. In pressing forward with diplomacy, his team’s objective should be for Iran to give up the option of developing a nuclear weapon forever—tangibly, not just rhetorically. A related objective is to limit the numbers and kinds of ballistic missiles Iran can develop. Moreover, Washington must ensure that its allies show a united front in support of these objectives—potentially including the “snapback” of UN sanctions if Tehran is not responsive.

In short, the more Iran is isolated politically, the greater the chances of success in reaching nuclear and missile agreements. Such leverage can be both positive and negative, involving inducements and pressure alike. As Iranian leaders ponder what is next, now is not the time to let them believe that the international community will simply accept the ceasefire on its own and do nothing more to limit their nuclear and missile capabilities.

Negotiating Nuclear Restrictions

Richard Nephew

Iran’s nuclear program has been dealt a heavy blow since June 13, yet estimates vary as to the overall effect that military strikes had on the regime’s ability to rebuild the program and stage a breakout. Hence, a key objective of initial talks should be to insist that any attempt at reconstituting the program would constitute a breach of the ceasefire. This includes any efforts to salvage components or materials outside the eyes of foreign inspectors.

In the longer term, negotiators should focus on provisions that prevent Iran from reconstituting those parts of the program that could enable weapons production (e.g., by prohibiting uranium enrichment and research on spent fuel reprocessing). Tehran should also be required to provide the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) with perpetual access to the program and reaffirm its commitment to the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty. Disposition of its remaining stocks of 60 percent and 20 percent enriched uranium is essential as well, along with declaration and disposition of any centrifuge components and any items that could support a weaponization effort. (For more on these technical issues, see the Washington Institute’s Iran Nuclear Glossary.)

Iranian officials will no doubt object to these measures, pointing to President Trump’s own statements that the nuclear program is completely smashed as proof that it no longer constitutes a threat. In particular, Tehran will refuse to cede its right to enrichment; rather, it will argue that rebuilding its nuclear facilities will take years, so the international community should use that time to pursue confidence-building steps that gradually erase the current objections to an Iranian enrichment program. The United States must therefore identify ways to navigate through this negotiating stratagem, perhaps focusing on civil nuclear cooperation and the construction of new reactors as a benchmark for any future consideration of fuel production. Additional provisions could stipulate that the initial batch of reactors built under this arrangement must receive their fuel from abroad, essentially shelving the thorny issue of domestic Iranian enrichment rights for years or even decades.

The Missile and Drone Angle

Farzin Nadimi

Israel’s air campaign heavily damaged Iran’s missile infrastructure, destroying many launchers and key production sites such as solid- and liquid-fuel plants, engine facilities, and factories that produce transporter erector launchers (TELs). Still, some hardened, dispersed assets and stockpiles survived.

From a personnel standpoint, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) missile force lost much of its top command early in the war but was able to continue firing at Israel, though mass salvos gave way to smaller barrages as attrition to Israeli airstrikes set in. Most of these strikes were intercepted by Israel’s multilayered defenses, but enough missiles got through to cause substantial damage and casualties. Iran also launched over a thousand one-way drones, but the majority were shot down by allied air defenses.

These outcomes will likely have important effects on Tehran’s strategic calculus. The war provided a stress test for its “direct deterrence” model of launching missiles and drones from its soil, highlighting both the resilience of this approach (because Iranian forces continued launching missiles and causing significant damage to Israel despite efforts to stop them) and its limits (because Israel intercepted the majority of these missiles, established air dominance, and, given time, could have posed an even greater challenge to missile supply chain and exposed launchers). Similarly, almost all of Iran’s drones were shot down before they reached their targets.

In response, authorities will presumably double down on the missile program, rebuild its infrastructure, address its vulnerabilities (possibly with Chinese help), and aim to improve the arsenal’s accuracy and penetration capabilities. They might also exploit dual-use programs such as space launches in a bid to mask these activities.

After losing control of its airspace, Iran currently has just one pillar of its deterrent posture left standing: its relatively elusive ballistic missile force. As such, it will continue investing in replenishing these stocks with high- and low-end missile systems, aiming to develop more effective, versatile, and survivable platforms and tactics capable of penetrating advanced enemy defenses and achieving strategic effects with a smaller footprint and fewer launches. These replenishment and development efforts will almost certainly be attempted away from prying eyes, most likely within underground facilities as much as possible. Even aside from any potential advancements, the deadly impact of the few missiles that breached Israel’s defenses and devastated civilian areas underscores the urgent need to address the regime’s current ballistic missile capabilities in any upcoming nuclear talks.

Sanctions Relief

Patrick Clawson

Faced with a difficult economic situation, Iran is eager for sanctions relief, giving the Trump administration an opening to take some immediate steps. In the financial sector, U.S. pressure has led banks in several countries to partly or fully restrict Iran’s access to assets that totaled $100 billion at one point, mostly from oil sales. Yet even if Washington offers to grant Tehran access to those funds, regime figures might be skeptical given the difficulties they encountered finding banks prepared to honor similar agreements offered in the past, including the 2015 nuclear deal and a 2023 deal that was never implemented.

In the energy sector, President Trump reportedly told attendees at the June 25 NATO summit that he would not block Chinese purchases of Iranian oil. He may have meant that the administration would back off its stepped-up enforcement of sanctions, since fully permitting Iranian oil sales would require unwinding a whole series of executive orders and laws. In any case, world oil markets are amply supplied at the moment, so Iran would likely have to offer significant discounts to sell more than its current 1.65 million barrels per day.

Beyond those steps, U.S. pledges to ease sanctions would not necessarily lead to the main result Iran wants, namely, restoring normal business relations with the West so as to stabilize its economy. Financial institutions are still leery of Iran, not least because of warnings from the multinational Financial Action Task Force (FATF) that the Islamic Republic is a high-risk jurisdiction rife with money laundering and terrorism financing. A wide array of Iranian firms are subject to restrictions related to drug trafficking, human rights abuses, and terrorism, not all of which Trump can waive with executive orders. On top of the legal barriers, Iran has a poor business environment—corruption is chronic, regulations are stifling and erratic, and the regime’s security services often arrest foreign nationals on flimsy excuses, essentially holding them as hostages to pressure Western governments. For all these reasons, many foreign businesses will likely remain reluctant to get involved in Iran regardless of whatever relief the U.S. government offers.

The European Role

Michael Singh

With Iran’s nuclear program set back but not eliminated, the E3 (France, Germany, and the United Kingdom) will seek to negotiate a deal that uses inspection and verification to establish where those latent nuclear capabilities stand and constrain their growth. From the E3’s perspective, the alternatives—an Iranian nuclear program gone dark and unconstrained, or continual Israeli/U.S. military strikes—are far less palatable.

To achieve such a deal, however, the E3 must be at the negotiating table. They will seek to earn their seat by leveraging the possible “snapback” of UN sanctions, the authority for which expires in October. They will also need to coordinate effectively with the Trump administration, whose views on post-conflict diplomacy have ranged from insinuating that it is already under way to dismissing its necessity. Moreover, the E3 must move quickly, as the snapback mechanism must realistically be triggered by the end of July (given the sixty-day snapback process) if it is to be used at all. That means Washington must move quickly as well if it aims to wield the leverage afforded by snapback.

China and Russia’s Role

Grant Rumley and Anna Borshchevskaya

Although the Iranian regime is undoubtedly weaker as a result of the Israeli and U.S. strikes, it remains intact. This is a net positive for China and Russia. To be sure, this episode demonstrated the limits of their ties with Iran, since neither country was willing to intervene militarily in the war with Israel. Yet retaining these partnerships remains a key interest for all three parties.

In the near term, Iran will seek diplomatic support from Beijing and Moscow to bolster its positions in upcoming talks with the United States. Both governments will be more than willing to oblige, even if only to counter Washington and its partners. China will also seek assurances that the ceasefire will hold and that commercial traffic through the critical Strait of Hormuz will remain unmolested. Moreover, it will seek to use this episode to promote its own Global Security Initiative in contrast with the U.S. approach to international affairs.

Along the same lines, Russia will likely push for some kind of formal condemnation of U.S. and Israeli military action, offer to mediate ongoing disputes, and emphasize that Iran’s nuclear program was “peaceful.” It might also offer additional assistance to that program, though at this point Tehran likely has all it needs in terms of nuclear know-how.

Given these potential roles, the United States should seek to exclude both countries. Including Russia or China would only bolster Iran’s negotiating position while simultaneously elevating Beijing and Moscow’s influence in the Middle East.

Finally, while the upcoming negotiations may be focused primarily on the future of Iran’s nuclear program, the Trump administration should keep in mind that their repercussions will extend far beyond the Middle East in this era of great power competition. Accordingly, U.S. officials should be prepared to counter Russian and Chinese talking points, such as accusations that Washington violated international law and dismissals of international concerns regarding the nuclear program.

For media inquiries, contact: Jeff Rubin, press@washingtoninstitute.org, 202-230-9550