- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 4088

Iran Has Taken More U.S. Citizens Hostage. It’s Time to Shred the Regime’s Playbook.

Both before and after the twelve-day war, the Islamic Republic has taken U.S. citizens hostage, necessitating a multifaceted U.S.-led strategy that ends the practice for good.

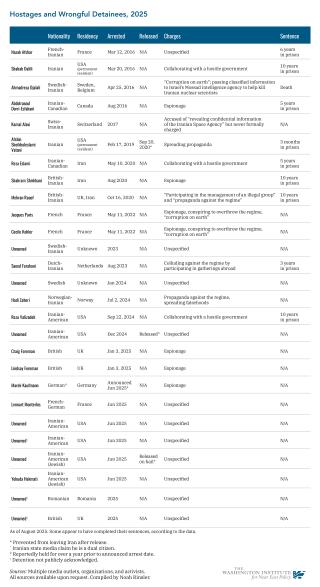

“ATTN ALL AMERICAN CITIZENS AND DUAL-NATIONALS: DO NOT TRAVEL TO IRAN,” warned a July 10 U.S. State Department advisory posted in Persian and all-caps English. While it is unclear how widely the message will reach beyond Washington, the warning is especially urgent in the post-twelve-day-war climate, during which at least five dual and foreign nationals—including some four Iranian-Americans—have been arrested, according to figures compiled by The Washington Institute (see below for a full list of current hostages and wrongful detainees).

Since the Iran hostage crisis of 1979–81, when revolutionaries held fifty-two U.S. diplomats for 444 days—and an additional fourteen citizens more briefly—the Islamic Republic has transformed hostage-taking into a tool of statecraft, a source of revenue, and a means of gaining the release of its own nationals—often closely tied to the clerical establishment. Former hostage Nizar Zakka, a U.S. permanent resident at the time of his recent detention, described Iran’s practice as a “business model,” noting that he took over the cell previously occupied by Washington Post journalist Jason Rezaian. Australian academic Kylie Moore-Gilbert, who was also held in Iran, observed a disturbing hierarchy: “Foreign prisoners fetch the highest price.”

The frequency of Tehran’s hostage-taking underscores the impunity with which the Islamic Republic operates. In some instances, hostage diplomacy comes with little punishment for the clerical establishment, and at times the practice is rewarded. An unprecedented moment occurred in June 2024, when for the first time a convicted war criminal—Hamid Noury, found guilty in Sweden for his role in the 1988 massacre of some five thousand political prisoners across Iran—was repatriated to Iran in a prisoner swap. In exchange, Iran released two Swedish nationals: European Union diplomat Johan Floderus and Saeed Azizi, who also holds Iranian citizenship.

While the twelve-day war in June set back Iran’s nuclear program, the fate of foreign and dual nationals remains unresolved, and was likely on the unofficial agenda at a July 25 meeting in Istanbul that included Britain, France, and Germany. But as former hostage and Iranian-American dual national Emad Shargi warned in a May CNN interview, the existence of talks should offer no comfort. “Every time there are talks scheduled between Iran and the United States,” he explained, “it’s open season for hostage taking in Iran”—because the clerical establishment uses detainees as leverage with the West. Additionally, on July 26, Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian called on the diaspora to return to the country, prompting the Special Presidential Envoy for Hostage Affairs’ official X account to reiterate its warning not to travel to Iran.

Why Do U.S. Citizens Travel to Iran?

For some, travel to the Islamic Republic is driven by the allure of encountering a U.S. adversary and deconstructing stereotypes about the country. In recent years, countless travel influencers have flocked to Iran to make the point that contrary to Western media and U.S. government claims, Iran is actually a “safe” place to go. Sympathy is certainly due to the Iranian people, who are recognized for their extraordinary hospitality. But the same cannot be said about the clerical establishment, which has brutally repressed its people for decades—including most recently during the 2022 Woman, Life, Freedom uprising, when it committed crimes against humanity, according to a March 2024 report from a United Nations fact-finding mission. Not just travel influencers face risks. Among those taken hostage are journalists like the Post’s Rezaian and Iranian-American freelancer Roxana Saberi. Academics have also been targeted, including Chinese-American Princeton graduate student Xiyue Wang.

For dual nationals, although dual citizenship is not recognized by the Islamic Republic, the motivations for traveling to Iran are typically personal—visiting oftentimes elderly or sick family members, attending weddings or funerals, managing a family business or inherited property. But many do not take the associated risks seriously, assuming that those who are arrested and slapped with unsubstantiated charges must have done something “wrong.” Thus, these dual nationals cannot even fathom being potential targets of the intelligence arm of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

Even former hostage Emad Shargi admitted to holding this belief—until it happened to him. In a July 10 public service announcement put out by the State Department, Shargi recalled, “Before I went to Iran, I thought, ‘This surely won’t happen to you. These things happen to people who have done something wrong, who have said things against the Iranian regime.’” Such a mindset is not exclusive to dual nationals. In 2009, when three Americans were captured while hiking in the Kurdish highlands of Iraq after accidentally traversing the border with Iran, much of the public reaction was described as “hiker hate” based on a feeling that “they got what they deserved.” This thinking suggests that the average American still does not comprehend the dangers of traveling to hostile countries like Iran.

Hostage Diplomacy as a Tool

Before the second Trump term, three consecutive U.S. administrations completed four hostage deals with Iran. Under President Obama, as part of the nuclear agreement known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, Jason Rezaian and three other hostages—Saeed Abedini, Amir Hekmati, and Nosratollah Khosravi-Roodsari—were released in 2016 in exchange for clemency granted to seven Iranians (six of whom were dual U.S.-Iranian citizens) and the retraction of Interpol Red Notices and charges against fourteen Iranian nationals. (A fifth U.S. hostage was released later.) Simultaneously, the United States returned $1.7 billion belonging to Tehran from a 1970s arms deal that was never fulfilled due to the Islamic Revolution. The first of two installments, $400 million coincided with the U.S. prisoner release.

Two prisoner swaps occurred during the first Trump administration. In 2019, Xiyue Wang was exchanged for Masoud Soleimani, an Iranian who had violated U.S. sanctions. And in 2020, Michael White was released in exchange for Majid Taheri, another Iranian convicted of violating U.S. sanctions.

The Biden administration brokered a fourth deal in 2022, securing the release of five Americans—including Emad Shargi along with Siamak Namazi and Morad Tahbaz—in exchange for five Iranian nationals who violated U.S. sanctions and committed federal crimes, even as three did not want to return to Iran. Additionally, $6 billion of Iranian oil revenue assets held in a South Korean bank was released and transferred to Qatar for humanitarian purposes such as food and medicine but refrozen after the October 7, 2023, Hamas-led terrorist attack against Israel.

In a July 20 CNN interview, U.S. Special Envoy for Hostage Response Adam Boehler acknowledged that the United States has “some [hostages] in Iran.” Presumably, the Trump administration is keen to get them released. While the State Department has taken important first steps—such as issuing its travel advisory and public service announcement featuring Shargi—the United States must do more to end the Islamic Republic’s forty-six-year enterprise of taking hostages and protect U.S. and dual nationals from the risks of travel to Iran.

The State Department should:

- Hold town halls in key diaspora cities—such as Los Angeles, New York, Seattle, and Washington DC—and air its PSA on widely viewed diaspora satellite channels like BBC Persian and Iran International as well as popular radio stations like 670 AM KIRN. U.S. Special Envoy Boehler should become a regular guest on these outlets to discuss the status of hostages and warn listeners not to travel to Iran.

- Produce an annual report detailing developments in hostage-taking as well as wrongful and arbitrary detention—naming responsible Iranian officials where possible—to ensure visibility and accountability.

The U.S. government should:

- Bar Iranian officials and their families from traveling to the United States.

- Deny U.S. visas to family members of regime officials and other insiders, including student visas to attend university here.

- Support efforts by former hostages to seek reparations in American courts by pursuing exceptions and modifications to the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act in both U.S. and international law.

- Increase efforts to establish a multilateral deterrence mechanism that enlists partners and allies to work together to raise the costs to Iran for its hostage diplomacy. The United States can show leadership by fast-tracking the development of deterrence tools across all elements of national power—diplomacy, economic, financial, information, intelligence, law enforcement, and military.

- Encourage Western allies to share their compiled lists of Iranian officials involved in hostage-taking, thus enabling Washington to refuse visa issuance and impose sanctions on the individuals in question.

- Use relevant sanctions authorities, including the Levinson Act, to target the hostage-taking enterprise, including intelligence officers.

Other steps:

- Issue a joint U.S.–European Union statement warning against travel to Iran, similar to the recent fourteen-country joint statement on transnational repression.

- Require that U.S. citizens obtain special endorsements or permissions to travel to Iran on an American passport. While many dual passport holders use their Iranian passport to enter the country, this measure would at least deter tourists from visiting.

- Advocate automated notifications or pop-ups warning of the risks associated with Iran travel on airline and tourism websites and social media platforms. Signs and informational pamphlets should likewise be placed at passport agencies, application centers, and U.S. embassies and consulates.

Holly Dagres is the Libitzky Family Senior Fellow at The Washington Institute and curator of The Iranist newsletter.