- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 4092

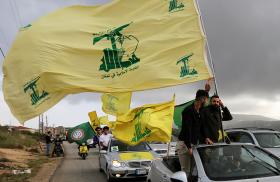

The Future of UNIFIL and Hezbollah Disarmament

Former Israeli and Lebanese military officials discuss whether the UN force can play any effective role in the urgent tasks of expanding Beirut’s sovereignty and disarming Hezbollah.

On August 14, The Washington Institute held a virtual Policy Forum consisting of two separate, sequential video conversations: one with Gen. Khalil Helou of the Lebanese Armed Forces, and another with Lt. Col. Sarit Zehavi and Brig. Gen. Assaf Orion of the Israel Defense Forces. Helou served in the LAF Rangers Regiment and the hostage rescue force of the military intelligence services; he is currently an associate professor at Saint Joseph University of Beirut. Zehavi served with the IDF Intelligence Corps and later founded Alma, an institute focusing on security challenges along the Israel-Lebanon border. Orion is The Washington Institute’s Rueven International Fellow, a senior research fellow at the Institute for National Security Studies, and former head of the IDF Strategic Planning Division. The following is a rapporteur’s summary of their remarks.

Khalil Helou

The UN Interim Force in Lebanon has been active since 1978 but proved unable to prevent a long series of wars: in 1982, 1992, 1996, 2006, and 2023-24. Notably, UNIFIL is in Lebanon under Chapter 6 of the UN Charter, so it is not a strike force. Hence, many in Lebanon are advocating that it be placed under Chapter 7 so that its mandate can be enforced militarily. Yet the permanent members of the Security Council oppose this move because they are reticent to get more involved in the Middle East. Absent a UN decision to give UNIFIL or another force the necessary resources and authorities, carrying out this mission against Hezbollah will not be possible.

If UNIFIL were not present in Lebanon, the LAF would have to take over its functions. This is a serious undertaking that would divert the LAF’s attention from the very porous 300-kilometer border with Syria. The LAF has secured hundreds of Hezbollah positions south of the Litani River, but it has other crucial missions. For example, one million Syrian refugees still remain in Lebanon, and terrorist organizations persistently try to recruit them; in the past few years alone, the LAF has foiled several terrorist operations. This is in addition to securing the maritime border. Without UNIFIL in the south, the LAF would have to move 5,000-10,000 more troops there from central Lebanon—a redeployment that would have consequences for the entire country’s stability and raise further questions about how to continue fulfilling LAF salary payments.

Apart from these military concerns, Lebanon has made a giant leap by removing Hezbollah’s political cover. Going forward, the group will likely maintain some presence in Lebanon, but weaker than before—a return to the status quo ante seems improbable. The government will be in a better position to convince allies to support the LAF, while gradually convincing Hezbollah to peacefully integrate into the political process.

The countries that fund UNIFIL—mainly the United States, which has provided $6 billion since 2006—are understandably dissatisfied with the results. Yet the force’s presence is still important for Lebanon, particularly its maritime branch. Over the past two decades, UNIFIL has hailed over 100,000 ships, more than 1,000 of which have been transferred to Lebanese authorities for searches. At present, the Lebanese Navy cannot undertake that responsibility by itself. For all of these reasons, UNIFIL needs to remain in Lebanon for the near future.

Sarit Zehavi

UNIFIL does not play a useful role—in fact, it is detrimental to the mission of disarming Hezbollah in south Lebanon. The organization’s mandate allows it to patrol freely in open areas to search for weapons caches, but it has done nearly nothing to confiscate these weapons or eliminate Hezbollah’s military infrastructure. Nineteen years since the passage of Security Council Resolution 1701, UNIFIL has offered proof of confiscating a grand total of one Hezbollah rocket launcher. The force also interfered with Israeli operations in the south during the 2023-24 war. Despite warnings from the IDF, UNIFIL elements refused to evacuate from the war zone; they even conducted patrols during certain battles, enabling Hezbollah fighters to flee.

General Helou correctly noted that getting the LAF to rise to this challenge will be a gradual process, and that no one should put the onus exclusively on Lebanon’s military in the near term. Hezbollah is a state within a state—not just with regard to its weapons, but in its network of services as well. To truly advance the prospects for change in Lebanon, all of these sectors need to be addressed. There can be only one state in Lebanon, and this entails removing Hezbollah from schools, banks, hospitals, and so forth.

Under the current conditions, if the IDF withdraws from the five hilltops it currently occupies in south Lebanon, then Israeli civilians who have returned to their homes across the border would turn around and leave. They will not tolerate living so close to an emboldened Hezbollah again. Israel needs to see deadlines and benchmarks that prove disarmament is actually happening, and these efforts should be combined with actions outside the military space. Yet UNIFIL cannot be fixed, so its mandate should not be renewed.

Assaf Orion

On the political level, UNIFIL is deployed to support the LAF and perform whatever the Lebanese government asks it to do in terms of implementing Resolution 1701. Yet as long as Beirut balks at demanding that UNIFIL disarm groups with prohibited weapons, the force will remain ineffective, and its reports will continue to misrepresent reality. As General Helou noted, UNIFIL does not have Chapter 7 authority. Its units are very cautious not to use the levels of force allowed by its mandate, not even in self-defense. This is primarily because UNIFIL commanders consider the goodwill of local communities as a vital condition for the force’s own safety. As such, UNIFIL engages in various humanitarian activities not stipulated in its mandate, such as building soccer fields, operating dental clinics, and spearheading livestock vaccination campaigns—all while failing in its core mission of preventing illicit arms in south Lebanon since 2006.

For years, the UN described “Israeli allegations” about Hezbollah’s prohibited military activity in south Lebanon and said it was “in no position to independently verify” them. Yet the latest war unveiled the underlying reality, vindicating Israel and destroying the UN’s credibility. UNIFIL has long emphasized the quantity of its activities but delivered very few substantive results. For example, General Helou noted that UNIFIL’s maritime force hailed tens of thousands of ships after 2006, but in all my years of IDF service, I can remember only one case in which a ship was seized for carrying weapons—and not for Hezbollah, but for Syrian rebels. I doubt any nation would approve such a large military force with such poor results for half a billion dollars a year.

The dilemma between UNIFIL, the IDF, and the LAF is one of basic trust. Israel is unlikely to fully withdraw from south Lebanon so long as the LAF fails to assert its sovereignty in places where Israeli forces are not active. At the very least, the LAF must agree to an airtight security arrangement and demonstrate that it will not allow Hezbollah to pass. UNIFIL cannot be trusted to perform this duty in the future, having failed so miserably in preventing Hezbollah military activity even near UN positions.

Regarding the U.S. role, one key question is who will lead and maintain continuity on Lebanese issues. Previously, Hezbollah was deemed the top military threat on Israel’s borders and a priority for Washington. Now that Iran has been hit and Hezbollah has taken serious blows, it is dangerously tempting to put Lebanon on the back burner and pursue other ambitious projects. Yet maintaining urgency, focus, and attention is crucial, so the UNIFIL mandate renewal process could be a useful platform to discuss Lebanese affairs multilaterally. For now, the mandate extension period should be shortened from a year to six months or less, ensuring that these issues come up for concerted international discussion again by next spring at the latest. Ultimately, however, if UNIFIL cannot be fixed—a scenario that seems quite likely given the current political obstacles—then it should be nixed.

This summary was prepared by Manuel de la Puerta. The Policy Forum series is made possible through the generosity of the Florence and Robert Kaufman Family.