- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 4082

After the Bombing: Iran’s Nuclear Options

While the recent military strikes against its nuclear program may further incentivize Tehran to go for the bomb, they may also complicate such efforts and give Washington more leverage to dissuade it.

Last month’s Israeli and U.S. strikes on Iran’s nuclear program have spurred debate regarding how much the program has been set back and whether Tehran will be further incentivized to go for the bomb. The answer is far from straightforward.

Damage Done

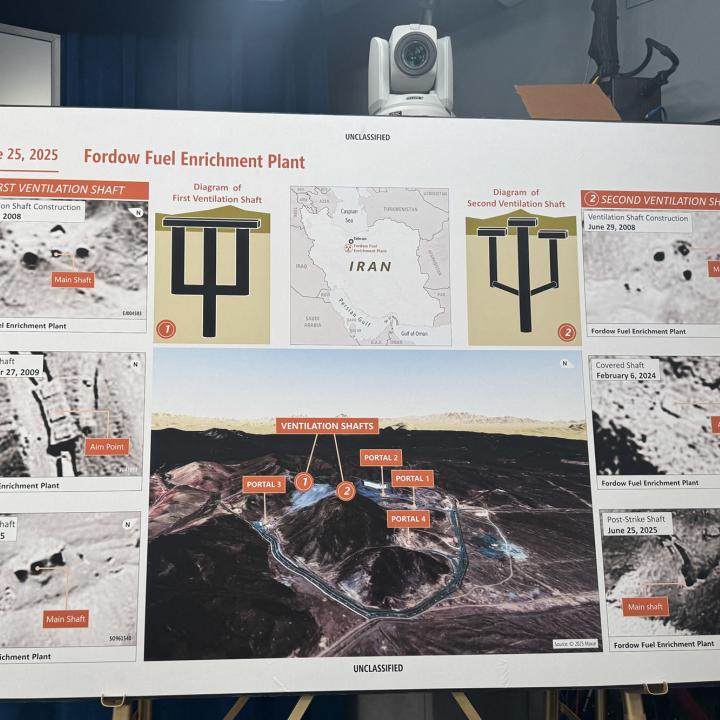

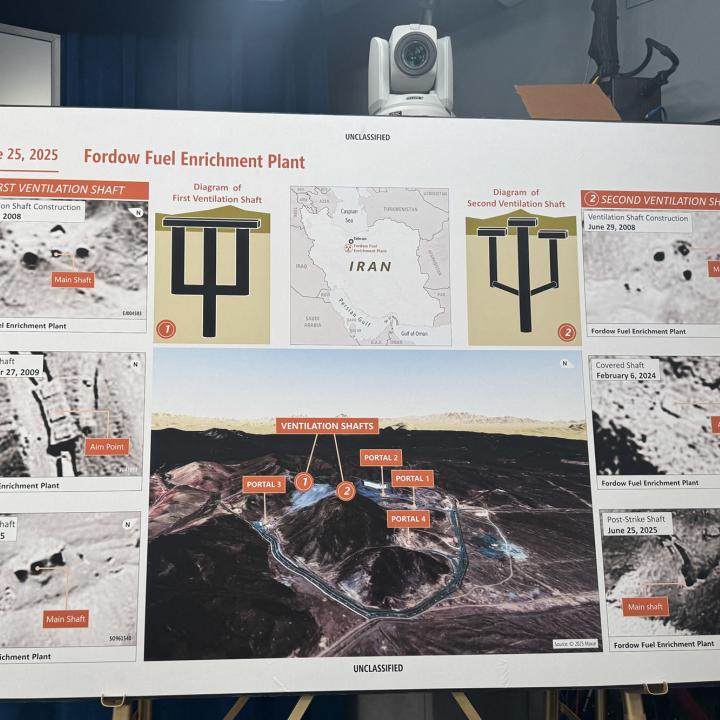

Israel reportedly struck about a dozen sites tied to Iran’s nuclear program and killed nearly twenty nuclear scientists—many engaged in weapons-related research. In addition, U.S. B-2 bombers dropped 30,000-pound Massive Ordnance Penetrators (MOPs) on the nuclear facilities at Fordow and Natanz, while submarine-launched cruise missiles struck Isfahan.

Experience has shown that it is difficult to destroy industrial sites from the air. Equipment pulled from the rubble can often be repaired or cannibalized and returned to service. However, the gas centrifuges that Iran uses to enrich uranium are finely tuned, delicate pieces of equipment that are easily damaged. According to Rafael Grossi, director-general of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the centrifuges at Natanz and Fordow were still spinning on the eve of the war. An uncontrolled shutdown would cause centrifuges to self-destruct; this is apparently how Israel sabotaged Natanz in 2021 and why it bombed the facility’s power source at the outset of the war last month.

Moreover, the twelve MOPs sent down the two ventilation shafts servicing Fordow probably destroyed the two centrifuge halls there. Even if they failed to breach the halls, the shockwaves created by the impact and explosion of these massive bombs likely defeated the damping measures taken to protect the centrifuges from vibrations and earth tremors. Thus, any centrifuge cascades not destroyed by the collapse of structures were probably damaged or destroyed by indirect effects. This may be why Grossi claimed on June 26 that Iran’s enrichment facilities “are not functioning anymore” and that its gas centrifuge program had incurred “very serious damage.”

Could Residual Capabilities Help Iran Rebuild?

Tehran might respond to the bombing by trying to create a small, highly compartmented, clandestine weapons program. Iran probably has spare centrifuges to replace those damaged through routine wear and tear. Moreover, the IAEA has stated that it has lost continuity of knowledge regarding Tehran’s gas centrifuge production since mid-2021. Thus, hidden stockpiles of gas centrifuges may be available to build a clandestine enrichment facility.

Furthermore, the status of Iran’s 440 kilograms of 60 percent enriched uranium—previously located at Isfahan, Fordow, and Natanz—remains unknown. This quantity, if further enriched to over 90 percent (weapons-grade), would be sufficient for about ten bombs. (For more on this and related technical matters, see The Washington Institute’s Iran Nuclear Glossary.) According to Israeli and American officials, much of the stockpile is buried under rubble at these locations. If that is so, some of the small cylinders used to store enriched uranium hexafluoride may have ruptured, causing the contents to decompose when exposed to heat or air. But others might be intact, and any Iranian attempt to recover these cylinders could provide an opportunity to target them. Moreover, some of the stockpile might have been diverted to other locations before the war and survived, as Iranian media have claimed.

If the regime diverted high-enriched uranium prewar or succeeds in recovering some from the rubble, the material would have to be enriched further to reach weapons-grade. (Some observers argue that a bomb can be built using 60 percent enriched uranium, but it would likely be unwieldy and produce a very low yield.) Iran could also acquire weapons-grade uranium from abroad—perhaps from North Korea.

The strike on Isfahan might also have destroyed equipment used to convert enriched uranium hexafluoride into uranium metal, as well as to cast and machine it. Strikes at other sites may have destroyed items used to produce the various non-nuclear components of a bomb. But Iran may have acquired some of these in duplicate, and at any rate, many of these tasks can be accomplished without specialized hardware.

Alternatively, Tehran may opt to not rebuild these capabilities as long as its nuclear program is penetrated by Israel’s intelligence services. At the very least, it will take time to thoroughly evaluate its options and choose an approach less vulnerable to disruption. (Iraq, for instance, took about a year after Israel bombed its nuclear reactor in 1981 to decide how to proceed.) Consistent with its proliferation strategy of the past two decades, the regime might adopt a slow, deliberate approach that seeks to move forward without rousing its enemies to action. Yet any efforts to revive the program will face Israeli covert and overt action to thwart it. For these reasons, focusing narrowly on technical considerations is unlikely to produce an accurate assessment of how long Iran could take to rebuild.

As for how Tehran might structure a rebuilding effort, it might construct small, clandestine facilities hidden in plain view at industrial sites, or in underground facilities beyond the reach of current conventional penetrator munitions. It could try to further mitigate risk by co-locating all enrichment and weaponization activities at one or two well-defended, deeply buried facilities—though this could wind up compounding risk should its enemies find an exploitable vulnerability (as at Fordow). Conversely, Iran could create small, dispersed, redundant facilities, though this approach would carry risks as well—namely, weapons components and personnel would need to be shuttled between sites during the manufacturing process, creating opportunities for disruption.

Israel’s ability to counter such efforts (with U.S. help) will depend in part on whether it continues to obtain exquisite intelligence on Iran’s activities, and whether it can generate synergies between covert and overt military action despite Iranian deception, denial, and deterrent efforts. It may also depend on whether Israel can increasingly bear this burden on its own should geopolitical pressures push Washington to focus more on China and other regions. Sustaining such efforts in the months and years to come could therefore pose major challenges for Israel.

Iran’s Choices, U.S. Options

The war undoubtedly energized those in Tehran who have long argued that the Islamic Republic should enrich uranium to weapons-grade and/or fast-track efforts to build a bomb. Less clear is how the strikes affected more cautious actors—foremost among them Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei—who may now be rethinking Iran’s nuclear hedging strategy. (Indeed, signs that Tehran had revived long-dormant weaponization R&D work more than a year ago indicate that such a rethink may have occurred before the war.) Tehran may therefore be tempted to eventually restart efforts to build a bomb while carefully testing to see if it can move forward without getting caught.

Although the case for the bomb may be stronger than before—now reinforced by a burning desire for revenge—the arguments for continued hedging are also more compelling:

- Iran is more vulnerable, while Israel and the United States are more determined and risk-acceptant than at any other time in recent decades.

- The regime remains penetrated by Israeli intelligence, which means that Jerusalem and Washington would likely learn about an attempted breakout in advance and take action to thwart it.

- Iran currently lacks the means to close its air defense capabilities gap, meaning it might remain vulnerable to attack for years to come.

- Iran might not be able to secure a nascent nuclear arsenal from sabotage by foreign intelligence services or diversion by domestic enemies, who could be tempted to use a “loose nuke” against the regime.

- A bomb might not deter attacks by Israel and the United States, just as Israel’s nuclear weapons did not deter attacks by Iran.

- Iran is in dire need of sanctions relief, and the only way to attain it is through a new nuclear deal with the United States.

Thus, Washington and its partners might still be able to shape Iran’s proliferation calculus even if a nuclear deal proves unattainable. In particular, they should seek to dissuade Tehran from attempting to revive the nuclear program by doubling down on the following measures:

- Indicate that any efforts to revive the program will be caught and thwarted by the United States and Israel.

- Continue efforts to penetrate the program by cyber and other means, with the aim of convincing Tehran that a nascent nuclear arsenal would be vulnerable to sabotage and diversion and would therefore pose a risk to the regime.

- Support Israeli covert action to disrupt any nuclear rebuilding efforts, and backstop these activities with the threat of renewed military action should covert action prove inadequate.

- Press other countries to forgo the transfer of air defense systems to Syria, Iraq, and Iran to ensure that the aerial corridor between Israel and Iran remains open.

- Emphasize that Washington would consider sanctions relief in return for a deal in which Iran permanently gives up all of its enrichment capabilities. At the same time, U.S. officials should stress that any attempt to rebuild these capabilities would spur stringent new sanctions and more rigorous enforcement in conjunction with France, Germany, and the United Kingdom—and could spark a new round of fighting that might jeopardize Iran’s economy, internal security forces, and senior regime leadership. Conversely, Tehran could create an environment conducive to successful negotiations by permitting the return of IAEA inspectors and providing them with unfettered access.

Finally, the United States and Israel should launch a quiet multimedia influence campaign in Iran to shape the domestic debate about nuclear weapons. This campaign should highlight the dangers that pursuing a nuclear arsenal poses to the Iranian nation—underscoring that the Islamic Republic’s nuclear ambitions are a driver of conflict rather than a source of security for the people of Iran and the greater Middle East.

Michael Eisenstadt is the Kahn Senior Fellow at The Washington Institute and director of its Military and Security Studies Program.