Lethal Attacks Show Strengthened Houthi Control over Red Sea Transit

Part of a series: Maritime Spotlight

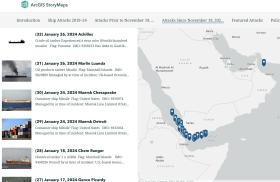

or see Part 1: Tracking Maritime Attacks in the Middle East Since 2019

The latest attacks make clear that the international community must guarantee the freedom and safety of all ships transiting the Red Sea, combining a permanent military mission with assistance from regional countries and private security firms.

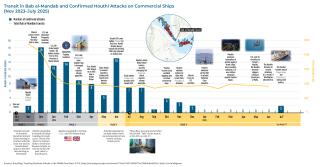

Last week, the Houthis dialed up their deadly kinetic campaign against freedom of navigation in the Red Sea, sinking two unescorted commercial vessels in consecutive coordinated attacks and doubling the number of ships sunk in the region since 2023 to four (see timeline chart below). The absence of an international naval presence in the southern Red Sea has likely encouraged the group to press on with the attacks; according to a report by Lloyd’s List Intelligence, the only entities able to intervene to rescue the seafarers were private maritime security firms, which have limited capabilities. Based on data that The Washington Institute has compiled since 2023, the attacks could have been mitigated had there been at least one warship on hand to respond to the first attack and intercept any additional weapons the Houthis launched.

A Continuation of the Houthi Maritime Campaign

The latest Houthi assaults can best be described as a textbook escalation, calculated to show capability and aggressiveness with maximum impact. Since 2023, the group has continued to experiment with new tactics and employed them at different stages of its maritime campaign. This time, the Houthis estimated that the risk was low and that they faced no credible rapid-response force, as they did in past attacks. The threat to shipping has never disappeared, and it was only a matter of time until the Houthis stepped up their attacks, which have been accompanied by well-organized propaganda warfare.

Even during the period of relative calm that followed a U.S.-Houthi “ceasefire” in May, the group continued to monitor Red Sea shipping, ensuring its presence was always felt through threats to shippers, mainly those with fleets calling at Israeli ports.

The latest attacks, against two bulk carriers operated by Greece-based companies whose vessels had visited Israeli ports, indicate that the Houthi threat will continue to linger, particularly as other regional conflicts pull international attention and military assets away from the southern Red Sea.

On July 6, the Houthis attacked Liberia-flagged bulk carrier Magic Seas (IMO 9736169), which is operated by Allseas Marine. According to a report from United Kingdom Maritime Trade Operations (UKMTO), Magic Seas was “engaged” by several small vessels before a projectile hit it, causing a fire onboard and forcing the crew to abandon ship. The seafarers were later rescued by a passing commercial vessel. A Houthi video showed militants boarding the bulk carrier, which later sank following multiple explosions in different sections of the ship just below the waterline, probably caused by hull-attached limpet mines.

The second attack this month, against Liberia-flagged bulk carrier Eternity C (IMO 9588249), operated by Cosmoship Management, caused numerous casualties among seafarers when Houthi gunboats directed their fire at the ship’s bridge. On July 9, UKMTO confirmed that the ship sank; the surviving crew members were reportedly taken hostage by the Houthis.

These were the first direct attacks against commercial vessels in the Red Sea since December 2024. (All information on past attacks can be found in The Washington Institute’s incident tracker.)

Unprecedented Scale and Boldness

The scale and boldness of the recent attacks were unprecedented, particularly amid the absence of any naval intervention. The Houthis used old and proven tactics such as manned and unmanned attack platforms and different types of missiles, some of which they employed in previous successful and failed attacks. These include the attacks against the container ship Maersk Hangzhou (IMO 9784300) in December 2023, which led to U.S. intervention to destroy Houthi boats, as well as last year’s separate operations against the general cargo ship Verbena (IMO 9522075), the bulk carrier Tutor (IMO 9942627)—which sank—and oil tankers Delta Blue (IMO 9601235) and Sounion (IMO 9312145), the latter of which was salvaged (more on this below). No single previous Houthi operation, however, blended all these domains into two well-planned and successful consecutive raids.

The Eternity C was reportedly struck with no less than eight swarming small craft including multiple explosive uncrewed surface vessels (USVs), two of which hit the ship while armed men aboard other boats were laying suppressive fire at the bridge and the defending security guards. At least two missiles targeted the ship at that time as well. Later, two more USVs and a missile impacted the now-stationary ship to finish it off. Based on the extent and location of damage from the cargo hold to the engine room, as well as the Houthi propaganda videos, it looks like a range of antiship ballistic missiles was used in the attack, including the electro-optically guided Asef and an antiship version of what appears to be a Qasim missile, as well as the radar-guided Mandab-2 antiship cruise missiles. The Houthis clearly intended to bring the ship to a halt and sink it with maximum effect.

The Houthi method of returning to stricken ships once they are abandoned to inflict the final blow and extract maximum propaganda value is not new, but it could have been countered this time if lessons had been drawn from past incidents and any warships in the region had rushed to the rescue.

In August 2024, an attack on oil tanker Sounion also included small arms and boats operated by the Houthis, who approached the ship before launching projectiles, causing a fire on board the tanker that later consumed the engine room, with the tanker starting to drift. At that time, the European Union defensive mission EUNAVFOR ASPIDES was able to respond to a request for help from the ship’s master.

The complexity and timing of the latest Houthi operations point to a higher level of coordination among their elements. The brutal attacks also coincided with a potential ceasefire in Gaza and took place amid ongoing tensions between Iran, on the one hand, and the United States and Israel, on the other. In addition, given that the Houthis had threatened to act against U.S. vessels even before the U.S. strikes on Iran’s nuclear facilities in June, any future escalation or de-escalation with Iran can be expected to affect Red Sea shipping.

The total absence of international military assets in the southern Red Sea signals to the Houthis that they are free to attack and sink commercial vessels at will. EUNAVFOR ASPIDES has only three naval units in the region, though it does offer escorts to commercial ships that request it. However, if the EU defensive mission had more assets at hand, it would be able to provide more protection, even though this would not be simple to implement, according to research conducted by the authors early this year. The rare presence of two U.S. Navy carrier strike groups in the Arabian Sea also failed to deter the Houthis.

Moving Forward

The Houthis have both the will and the military capability to sink more ships in the southern Red Sea, which is still a corridor not only for commercial shipping, but also for U.S. inter- and intra-theater military logistics in a volatile Middle East. Vessels at low risk will continue to transit the Bab al-Mandab Strait with caution, knowing that transit is down significantly from 2023—down by half, according to data from Lloyd's List Intelligence. Defensive operations like EUNAVFORASPIDES have no mandate to deter or defeat Houthi military capabilities. Even “comprehensive” offensive campaigns such as Operation Rough Rider, the U.S. operation against the Houthis in April and May of this year, could not guarantee freedom of navigation for all in the Red Sea, and major shipping companies continue to avoid the region.

If the Houthis continue to enjoy the freedom to attack ships in the region, vessels with indirect links to Israel, and in the future probably other ships as well, will require a military escort if they continue transiting the Red Sea. Shippers who are aware of these risks and decide nevertheless to turn off their automatic identification system (AIS) and transit without escort will be putting seafarers and their vessels at extremely high risk. Ships with links to the United States should also remain vigilant, despite the “ceasefire” with Washington.

This surge is not just symbolic escalation. The Houthi attacks were deadly and were well coordinated and disruptive enough to justify a permanent military mission, assisted by private maritime security firms and regional states, to guard freedom and safety of navigation for all in the Red Sea.