- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 4076

Now Is Not the Time to Ease Up on Hezbollah—or Beirut

After giving Lebanese officials a much-needed ultimatum for disarming Hezbollah and implementing financial reforms, Washington is now in danger of letting them once again punt these all-important tasks.

On July 7, U.S. Special Envoy Tom Barrack traveled to Beirut three weeks after giving the Lebanese government a letter demanding immediate steps to disarm Hezbollah and other militias. The June 19 ultimatum and accompanying roadmap for implementation gave Beirut several months to make significant progress toward this goal and initiate financial and economic reforms, reflecting Washington’s growing frustration that such efforts had stalled.

Lebanon offered an initial response to the letter during this week’s visit, and while the details have not yet been made public, Barrack said he was “unbelievably satisfied” with the reply. It is unclear why he was so pleased—unconfirmed reports from Lebanon and Israel suggest that Beirut merely re-committed to disarming Hezbollah south of the Litani River by the deadline, with wider disarmament occurring sometime in the future. If these rumors are true, the Iran-backed terrorist group will retain its weapons, and Lebanon’s chance to achieve sovereignty will be deferred or even missed entirely.

Diverging Approaches

After Hezbollah attacked Israel on October 8, 2023, in support of the Hamas invasion from Gaza, Israel responded with a limited war of attrition against the Lebanese militia. The crisis escalated further nine months ago, when Israel initiated a major campaign that severely degraded Hezbollah’s leadership, arsenal, and border deployments. These operations created an opportunity for Lebanese authorities to take long-delayed action of their own against the group, thereby curtailing Iranian influence in Beirut and establishing a truly sovereign state. Indeed, the November 2024 ceasefire committed Beirut to confiscating Hezbollah’s weapons and dismantling its military infrastructure throughout the state, while the newly elected president and prime minister pledged to implement sweeping financial reforms.

Yet the succeeding months have cast a stark light on Washington and Beirut’s diverging views regarding the urgency of these measures. The Trump administration correctly assessed that the moment for bold action is now, since Hezbollah is at its weakest point in decades but could once again reconstitute itself absent proactive Lebanese efforts to consolidate this degradation, much like it did after the 2006 war. Yet Beirut apparently calculated that avoiding a major confrontation with Hezbollah was more urgent than disarming it—a conclusion based not only on the group’s proven history of murdering political opponents, but also on wider fears of reviving the state’s long-dormant civil war.

From the beginning, President Joseph Aoun has stated that Beirut will not forcibly disarm Hezbollah. Instead, he has sought to convince the militia to give up its arms through negotiations or integrate with the Lebanese Armed Forces. Both of these approaches are problematic. Incorporating Hezbollah into the LAF would risk undermining one of Lebanon’s few functioning national institutions. Moreover, the previous two decades have proven such dialogue to be a standard delay tactic for Hezbollah and successive Lebanese governments, with the group treating discussions about a “national defense strategy” as a euphemism for keeping (and expanding) its arsenal.

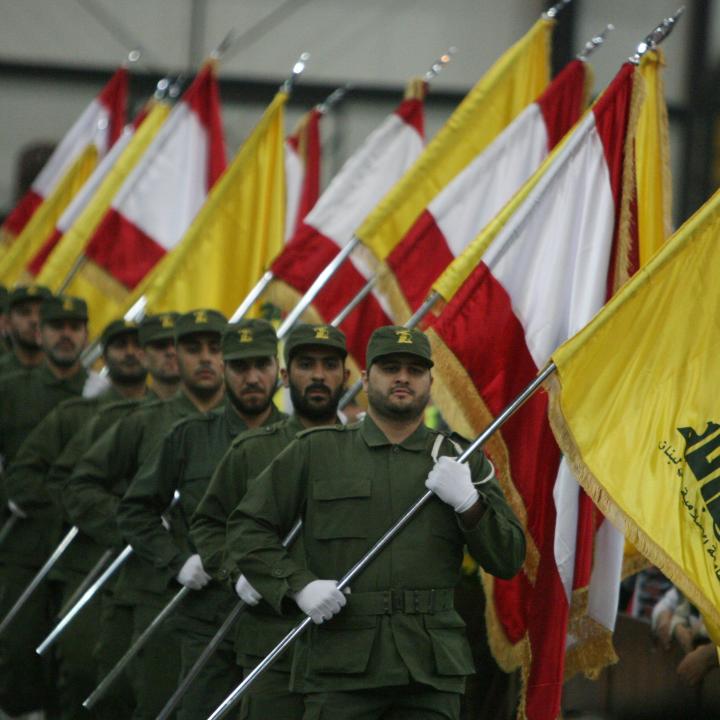

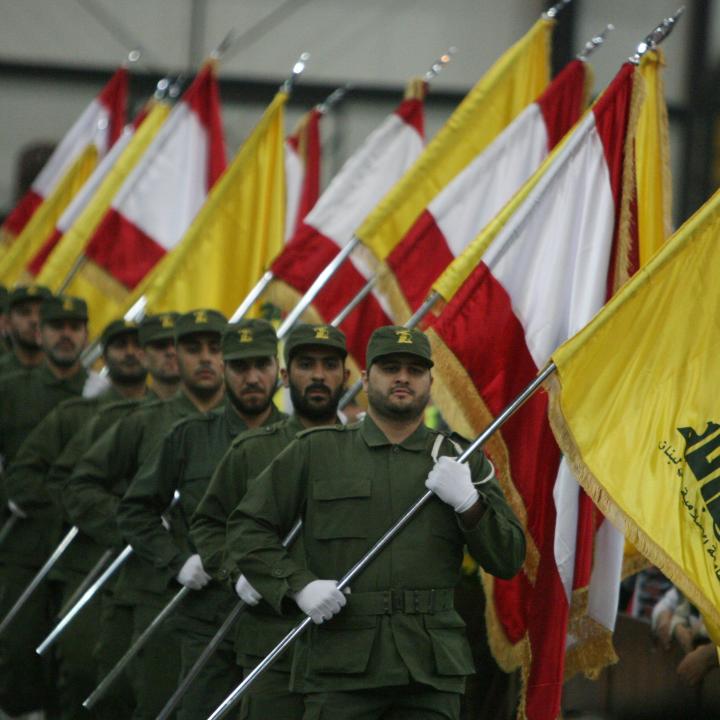

Today, Hezbollah says it has no interest in disarming—Secretary-General Naim Qassem has indicated that it will not discuss a “national defense strategy” or the disposition of its weapons until Israel fully withdraws from Lebanese territory. As for Barrack’s ultimatum, Qassem declared, “We have the right to say ‘no’ to them, ‘no’ to America, ‘no’ to Israel.” And during a July 5 procession in Beirut commemorating the Shia holiday of Ashura, Hezbollah members struck a defiant tone by brandishing their weapons in the streets of the capital.

Lost Momentum

The current state of affairs is particularly disappointing given U.S. and Israeli optimism after the November ceasefire. Initially, the LAF was responsive to tasking requests, repeatedly confiscating Hezbollah weapons and dismantling infrastructure when notified of their location by the U.S.-led ceasefire mechanism, which is largely based on Israeli intelligence. While taking pains to be as nonconfrontational as possible, the LAF was largely effective, taking action against more than 400 Hezbollah sites south of the Litani River. Yet efforts to demilitarize the group north of the Litani were never as robust and have since stalled—not because the LAF is unwilling, but rather due to a lack of political guidance from Beirut.

The new government has yet to pass the requisite financial reforms either. Sweeping legislation is desperately needed to extricate the state from a crisis that has included a 98 percent currency devaluation since 2018, a 40 percent contraction in GDP, and banking losses of nearly $80 billion. Yet the parliament—led by Speaker Nabih Berri, a staunch Hezbollah ally—has only passed one such measure so far, a banking secrecy law. Despite the urgency, legislators have been loath to make difficult and likely unpopular austerity decisions prior to next year’s parliamentary election.

The loss of momentum has frustrated Lebanon’s foreign supporters, with Washington and the Gulf states increasingly turning their attention to other regional priorities. Improbably, Syria seems to have supplanted Lebanon as the more promising bet. During his May visit to Riyadh, President Trump publicly mentioned Lebanon just once but met directly with Syria’s new president and declared that he would lift all sanctions on Damascus. Gulf reconstruction money is now flowing into Syria while Lebanon languishes in the rubble of war. In addition, Syrian officials have been meeting with Israel and reportedly considering more normal relations with Jerusalem, even as Lebanese legislators squabble over how best to placate the terrorist militia that has repeatedly brought Israeli military destruction raining down upon their country.

Policy Recommendations

Lebanon’s response to Barrack’s ultimatum should have been an inflection point. If Beirut had affirmed that it would take more proactive steps to confiscate the remainder of Hezbollah’s weapons, the United States could have pressed for the cessation of Israeli airstrikes, the withdrawal of remaining Israeli forces, progress on delineating the border, and postwar reconstruction.

Instead, Barrack was inexplicably conciliatory toward Hezbollah, describing Iran’s top terrorist proxy in the Middle East as a “political party” that “also has a militant aspect to it.” The administration is apparently trying to cajole the group into capitulating, but now is hardly the time to go soft on Hezbollah or Beirut.

If Lebanon once again punts on reform and wider disarmament efforts, Barrack says the US would politically disengage. Washington has several other options:

- Sanction Nabih Berri and other parliamentarians who obstruct progress.

- Slow-roll U.S. support for the international financial institutions that would bankroll Lebanon’s reconstruction (e.g., the World Bank and IMF), encouraging other donors to do the same. Saudi Arabia has already independently warned Beirut that no aid will be forthcoming unless Hezbollah disarms.

- End or dramatically curtail the United Nations peacekeeping mission. The Security Council is currently discussing whether to renew the mandate of the UN Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL), whose more than 10,000 troops in the south—the densest concentration of peacekeepers on earth—have long disincentivized the Lebanese government from exercising sovereignty there. Now more than ever, shaking up this dysfunctional dynamic could spur Beirut to action.

- Get more serious about targeting Hezbollah’s influence within the Lebanese state. Existing U.S. sanctions have largely focused on Hezbollah’s own finances. To break the organization’s grip on Lebanon’s security institutions, however, the Trump administration should consider targeting the key officials within these institutions who collude with Hezbollah. Washington could also press for the LAF and Internal Security Forces (ISF) to end their coordination with the militia.

In the meantime, Israel will undoubtedly persist with its now-routine airstrikes on Hezbollah targets throughout the state. In fact, given the Lebanese government’s longstanding aversion to confronting the group, Israeli military action might be Beirut’s preferred scenario. In the decades since the civil war, Lebanese officials have generally punted on difficult issues to avoid rekindling that devastating conflict, and their apparent response to Barrack is consistent with this approach. Yet it is hardly “safe” to keep deferring the problem of Hezbollah’s weapons, which have all too often been trained on the Lebanese people or invited Israeli attacks.

The new government in Beirut clearly wants to end Israeli strikes and preserve its relationship with Washington. Yet as long as Hezbollah retains a residual military capability, Lebanon’s politics will not reflect the new postwar reality, and sovereignty will remain elusive.

David Schenker is the Taube Senior Fellow at The Washington Institute, director of its Rubin Program on Arab Politics, and former assistant secretary of state for Near Eastern affairs in the first Trump administration.