Leaders in Tehran are saying they won the June war and can stand up to Israel, leaving U.S. policymakers with the tricky task of how to stand up to Iran.

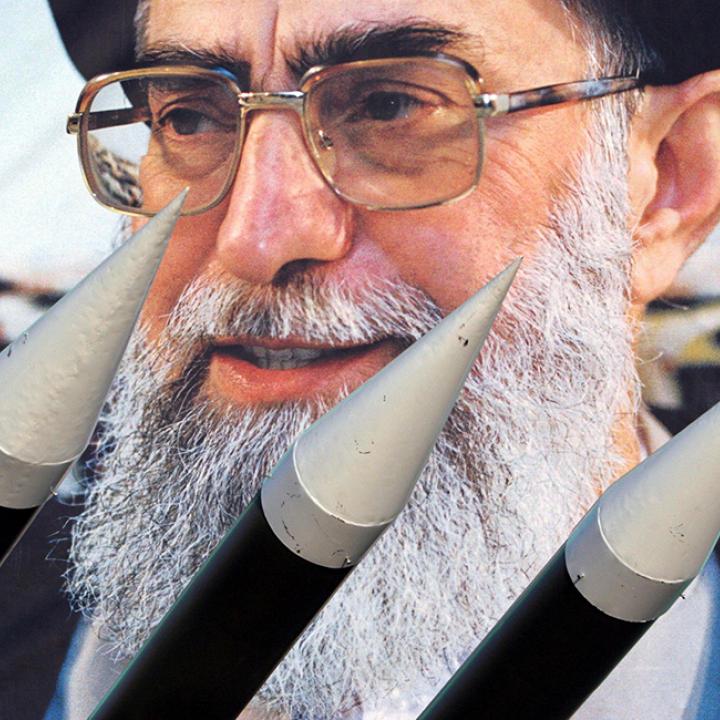

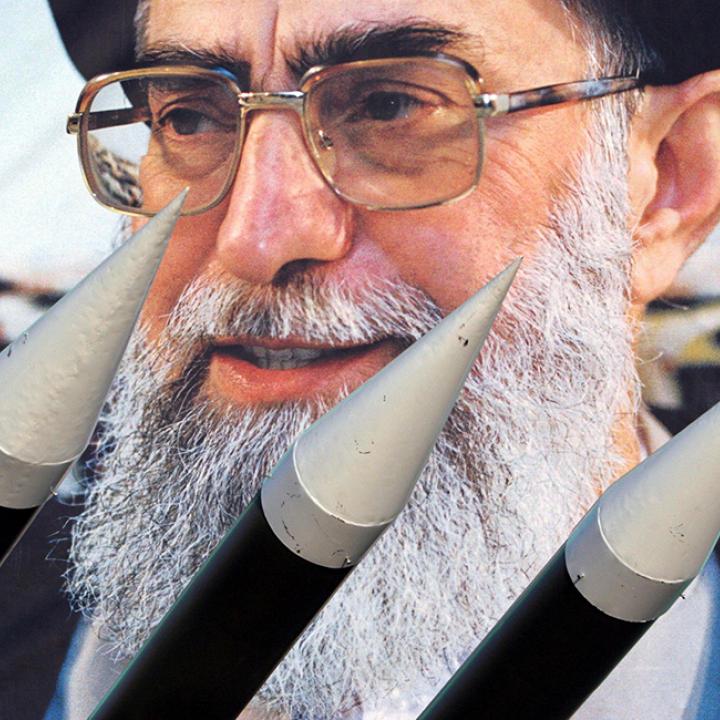

Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s speeches are an excellent indicator of where the Islamic Republic stands, and his past several months’ worth of remarks (readily accessible in a wide array of languages on his website) reflect increasing confidence on that point. To be sure, Khamenei was visibly shocked in the immediate aftermath of this summer’s twelve-day war. His June 26 speech was entirely out of character—he appeared tired, dare one say feeble, and emphasized broad nationalist themes rather than reinforcing the regime’s Islamic ideological foundations. He then went uncharacteristically quiet, only appearing on occasion in carefully controlled settings, unlike his prewar wont.

Khamenei regained some of his composure in a September 23 televised address, though his tone was still defensive. He complained about enemy “agents inside Iran, in Tehran,” claiming, “There are some—whose origins are abroad, according to the information we’ve received—who are trying to create the impression that the unity that emerged during and after the Twelve-Day War was only temporary.” And rather than expressing confidence that Iran could prevail diplomatically, he warned against holding new talks: “If you were to negotiate with the other side and accept their demands, that would mean submission, the weakening of the country, and the destruction of a nation’s honor...In my opinion, negotiations with the United States over the nuclear issue, and perhaps over other issues as well, are a complete dead end.” What was his solution? “The key to the country’s progress is becoming strong,” he said—a far cry from his past declarations that Iran is already more than strong enough to resist enemy pressures.

By last month, however, the prewar Khamenei had returned in full. Despite showing signs of aging more rapidly, the eighty-six-year-old leader was articulate and full of bluster during his October 20 speech to a group of sports champions, striking an openly triumphant tone about Iran’s performance during the war: “Iranian missiles were able to penetrate into the depths of several of the Zionist regime’s important centers to destroy and eliminate them...[Israelis] were struck such a hard blow they couldn’t believe it. They weren’t expecting it, and they’ve lost hope. [Trump] went there to raise their spirits. He went there to pull them out of their despair.” He even boasted that Iran is ready for another round: “Our Armed Forces and military industries had these missiles ready. They used them, they employed them, and they still have more. Should the need arise, they will be used again...These missiles were made by young Iranians. We didn’t purchase them from anywhere else.” In contrast to Iranian confidence, he noted that seven million “people across all U.S. states are chanting slogans against [Trump] in the streets.”

Iranian Analysis Supports Khamenei’s View

Khamenei’s declarations are no doubt jarring to American ears accustomed to hearing about Iran’s defeats and Israel’s triumphs. Yet it is important to realize that Iranian leaders have a detailed explanation for their entirely different narrative. Perhaps the fullest and most articulate exposition was delivered by Ali Larijani during a seventy-minute interview with Press TV on July 4 (dubbed into English here and here). The secretary of the Supreme National Security Council, he has become the Islamic Republic’s go-to person for sensitive diplomacy and clearly has Khamenei’s ear.

Larijani’s July interview laid out the underlying argument that “Iran was truly victorious” in the twelve-day war. After acknowledging the heavy blow that Israel struck on the campaign’s opening day with attacks on Iranian officials and scientists, he argued, “Over time, Iran gained the advantage...Israel is sinking and struggling...[T]he enemy has been defeated on the battlefield.” To support these claims, he quoted various Israeli sources at length, including former prime minister Ehud Olmert, current finance minister Bezalel Smotrich, television channels 12 and 13, and the newspaper Maariv, showing a detailed mastery of Israeli reporting and analysis on the war.

These views are not entirely fantastical. The fact is, Iran’s missile strikes inflicted damage on key Israeli targets such as the Haifa oil refinery, several military installations, and dozens of top national research labs at the Weizmann Institute of Science; indeed, Larijani quoted President Trump to this effect. Even when acknowledging that Iran’s available missile stocks declined sharply as the days went by, Larijani pointed to Israeli and American statements that their stocks of antimissile systems were also running low. And much like other Iranian officials, he concluded that the Islamic Republic was better placed than Israel to continue the war, saying Tehran never asked for a ceasefire while Israelis were the ones “begging” to end the fighting. He also argued that Trump ordered a ceasefire well before Israel had destroyed many important targets—a decision that Larijani read as proof that Washington and Jerusalem were afraid to keep the war going.

U.S. Policy Implications

Perhaps Tehran is overemphasizing U.S.-Israeli shortcomings and projecting self-confidence as its own form of deterrence. Iranian leaders often misunderstand their own military operations, claiming they have inflicted more casualties than is the reality. For instance, Larijani confidently asserted that six Iranian missiles hit U.S. facilities in Qatar during the war, ridiculing the (correct) U.S. statement that only one hit. Accordingly, Washington should begin providing ample, widely publicized, incontestable proof whenever it issues statements about hostilities with Iran.

It is quite possible that Tehran does not feel cowed by its recent military setbacks, contrary to conventional wisdom in Washington. Yes, the regime’s actions have been rather cautious since the June war, and its publicly declared analysis is demonstrably wrong or at least exaggerated. Yet this analysis might in fact be Iran’s actual view, and should therefore be factored into U.S. assessments of what the regime may do next.

Notably, Iran’s leaders—unlike its people—do not seem particularly worried that the country is vulnerable to Israel (or the United States) taking further military action. They appear to believe they have ample means to respond to any such attack; in other words, if Israel “miscalculates” and strikes Iran again, they could hit back in ways that leave Israel worse off.

Such optimism also seems to have left Tehran with no sense of urgency about reviving nuclear negotiations. Rather than feeling “maximum pressure” from the June strikes, Iranian leaders apparently believe they can prevail in a military conflict, removing the need to hurry back into talks with the West. Their recent actions have been consistent with this view. Tehran has been largely uninterested in reopening negotiations with Europe or the United States; most recently, Foreign Ministry spokesman Esmaeil Baqaei stated on November 3 that the latest exchange of messages with Washington did not mean nuclear talks had resumed. “Conditions are not ripe for a meaningful dialogue,” he explained.

Meanwhile, Khamenei’s public stance is growing more “resistant” by the day. During a November 3 meeting with students to commemorate the 1979 seizure of the U.S. embassy, he declared, “If they [the United States] stop supporting [the] Zionist regime, remove military bases from the area, and stop interfering in the region, these matters could potentially be reviewed. This isn’t something foreseeable for now, nor for the near future.”

In short, Iran is not acting like a country that needs to ward off further attacks. Instead, it appears quite confident about its strategic situation. Hence, the base case for future U.S. planning should be that no lasting agreement will be reached with Iran, and that the regime will continue searching for aggressive ways to challenge U.S. interests.

This does not mean Tehran is currently ready to resume engaging in or supporting attacks on U.S. facilities and personnel. As in the past, it is quite willing to bide its time, waiting for a propitious moment to act. Washington should therefore keep up its guard against unexpected moves.

In that regard, U.S. officials should take note of how the Iranian statements described above emphasized the missile program as much as the nuclear program; Tehran’s foreign allies and proxies were hardly mentioned. This may indicate that Iranian officials will be shifting more of their deterrence efforts to missiles rather than proxies, possibly even surpassing nuclear progress. Indeed, Iran is busy rebuilding the missile factories destroyed during the war, helped by dual-use inputs from China (e.g., sodium perchlorate). While U.S. analysts have largely focused on whether and how Iran is reconstituting its nuclear program, equal attention should be devoted to how quickly it can replenish its stocks of missiles and launchers, since this may be a better indicator of when Tehran will have the confidence to openly and directly challenge Israel and the United States again.

Patrick Clawson is the Morningstar Senior Fellow at The Washington Institute and director of its Viterbi Program on Iran and U.S. Policy.