- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 4080

Israel’s “Tribal” Approach in Gaza: A Short-Term Response to a Long-Term Challenge

Tribal militias in Gaza can offer limited tactical help if they are carefully monitored and managed, but relying on them would just be another way of delaying the more important work of formulating postwar political arrangements.

Amid military operations in Gaza and parallel ceasefire negotiations between Israel and Hamas, one critical question has yet to be sufficiently answered: Who will govern the Strip the “day after” Hamas? Israel’s military campaign has degraded the group’s conventional capabilities and turned it into an underground guerrilla force, but no clear alternative has emerged to replace its governance functions. In this vacuum, Israel has been engaging with local tribal actors as part of an improvised effort aimed primarily at undermining Hamas, with the additional objectives of stabilizing the area and enabling humanitarian aid distribution.

Despite the potential short-term benefits, however, this approach carries inherent risks that will need to be managed carefully. Officials must also account for the fact that relying on such clans only defers rather than resolves the “day after” dilemma.

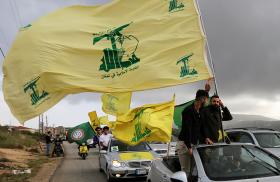

The Emergence of Tribal Militias

In early June, Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu acknowledged Israel’s cooperation with “tribal elements” to facilitate aid deliveries via the U.S.-backed Gaza Humanitarian Foundation (GHF). The most prominent of these elements is a Rafah-based militia known as the “Popular Forces” and led by Yasser Abu Shabab—a member of the Bedouin Tarabin tribe whose background in smuggling and petty crime created constant friction with Hamas in the past and led to his imprisonment. Although Netanyahu did not mention Abu Shabab’s group by name, it is widely understood that he was referring to them.

According to media reports since the end of June, two additional militias are operating with Israel in Gaza: one led by Rami Khiles, the head of a large family in Gaza City affiliated with Fatah, the party that heads the PA; the other led by Yasser Khanidek, a Fatah-affiliated figure operating in Khan Yunis. Yet Israel apparently provides more material support to Abu Shabab’s faction than either of these other groups, enabling the Popular Forces to operate in more of a paramilitary capacity.

Abu Shabab’s militia began openly operating in late May with a force of about 100-300 armed men. In a June 9 post on his Facebook account, he called on Palestinian academics and professionals to join the group in order to establish administrative and community committees in various areas, implying a kind of civilian government alternative to Hamas. On July 7, he claimed that this recruitment drive had resulted in 6,000 Gazans applying to join the group’s armed forces and another 3,000 applying for work in the civilian field. These numbers are almost certainly exaggerated.

Whatever its size, the group has projected a quasi-civic image emphasizing pan-Palestinian rhetoric and vague gestures toward coordination with Egypt and the PA. Abu Shabab publicly denies any Israeli sponsorship, but videos and field reports clearly document his group engaging in operational coordination with the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) and GHF.

As for the effects of such activity on the ground, the UN human rights spokesperson reported that 615 Palestinians had been killed in the vicinity of GHF humanitarian aid distribution centers as of July 7, some apparently by gunfire from the Popular Forces and other Israeli-supported militias. It is unclear how reliable these figures are.

For its part, Hamas seems to view the rise of Abu Shabab’s group as a threat to its own grip on Gaza. On July 1, the Hamas Interior Ministry accused Abu Shabab of treason and espionage, declaring that he must turn himself in and that he will be prosecuted even if he remains at large.

Legitimacy Deficit

Despite his efforts to craft a strong public image, Abu Shabab’s militia suffers from an acute legitimacy problem among Gazans, who widely view him as a collaborator. Even his own clan is divided, with some members publicly distancing themselves from his activities. Allegations of militia violence against civilians near aid distribution centers have only deepened the public hostility.

Recent Israeli policy announcements have made it even more difficult for groups like Abu Shabab’s to cultivate local legitimacy, since they are inevitably seen as tools of these policies. Earlier this month, Defense Minister Israel Katz and other officials publicly discussed plans to establish a “humanitarian city” in southern Gaza from which residents would not be permitted to exit, raising widespread concerns that it would become a de facto internment zone. There is also lingering concern that Israel will seek to force Palestinians out of Gaza, despite Netanyahu stating during his latest trip to Washington that any emigration would be voluntary.

Why Is Israel Working with Such Groups?

As noted above, supporting the Popular Forces militia is essentially a limited operational measure intended to undermine Hamas’s public image, improve the response to urgent humanitarian needs in southern Gaza, and stabilize the security situation there. From this perspective, backing such groups is not an illogical or entirely futile initiative.

Yet the use of tribal militias fits other Israeli government objectives as well. It is partly a tactical measure to reduce IDF casualties. It also fits with a broader Israeli political logic—namely, allowing the government to maintain de facto control in Gaza without formally empowering Hamas or the PA, and without facing the political risks of engaging the PA. This aligns with Netanyahu’s repeatedly articulated doctrine of “neither Hamastan nor Fatahstan.”

An Old Model with Inherent Limits and Risks

Working with questionable local forces is hardly new for Israel, or numerous other countries for that matter. From the 1970s until its 2000 withdrawal from Lebanon, Israel supported the South Lebanon Army, a Christian-led group; it also worked with Phalangist elements there. Notable international precedents include the U.S.-supported “Sons of Iraq” and the Afghan Local Police, both of which collapsed following U.S. withdrawals. Indeed, such groups have consistently suffered from poor cohesion, corruption, limited loyalty, and, most critically, a lack of broad legitimacy. Even if they had checked all those boxes, their affiliation with foreign powers seeking to reorder local political realities would have rendered them unsustainable once their external support waned.

In Gaza, tribal militias could provide significant short-term utility on securing aid routes, reducing Israeli casualties, and weakening Hamas’s monopoly on force. Yet the strategic and ethical risks are significant. Empowering such groups in a highly fractured society can accelerate internal conflict and empower criminal elements—without strict oversight, they could even morph into rogue actors who fuel instability rather than mitigate it. Moreover, if the widespread perception lingers that they are tools of the occupation, it will only deepen anti-Israel sentiment among the Palestinians.

Policy Recommendations

To maximize the tactical effectiveness of using tribal militias, minimize the strategic blowback, and curtail casualties among Palestinian civilians and IDF troops, Israel would need to consider the following measures:

- Establish effective control over militia weapons stockpiles to prevent terrorist and criminal elements from gaining access to these arms.

- Establish clear procedures for the use of weapons in order to prevent mass killings, gang wars, and other violations.

- Integrate these efforts with a broader regional strategy. Any tribal arrangement should be incorporated into Israel’s broader dialogue with Egypt, the Gulf states, the PA, and the United States. Among other benefits, this expanded approach could help the parties maintain flexibility in case the tribal model fails.

At the same time, however, Israeli officials need to acknowledge that this approach is neither a solution to Gaza’s complex humanitarian reality nor an adequate replacement for a coherent “day after” political plan. The role of tribal militias must be confined to short-term stabilization; they should not be thought of as a long-term governance option.

In the longer term, a political solution in Gaza is the most viable path, with the PA being the “least bad” option among the realistic alternatives. In order for this to occur, the PA must undertake significant reforms in its mode of governance that enable it to reassert control over Gaza and thereby reduce Israel’s need for direct involvement in the Palestinian arena.

For its part, Israel must internalize the strategic imperative of fostering a legitimate political and governmental framework within the Palestinian sphere. Otherwise, it risks nurturing the rise of more problematic scenarios—whether in the form of chaos or a one-state reality for two peoples.

Neomi Neumann is a visiting fellow at The Washington Institute and former head of the research unit at the Israel Security Agency.