- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 4098

Iran’s Nuclear Reconstitution Options

Iran’s leaders have several paths to restoring or reconfiguring their nuclear program—some more realistic or risky than others—so Washington should focus on shaping which route they choose rather than discounting the possibility altogether.

Immediately following the cessation of hostilities between Israel, the United States, and Iran in June, debate erupted about Tehran’s ability to reconstitute its nuclear program. Yet there has been less public consideration of what rebuilding might actually mean. Iran took the better part of twenty years to build the program in the first place; does it intend to follow that blueprint again or build something different?

Warring Timelines and Definitions

The Trump administration initially claimed that the nuclear program was “totally obliterated” and that Iran would not choose to rebuild its uranium enrichment capabilities, essentially precluding any estimated timelines for potential reconstitution. Shortly thereafter, however, U.S. language shifted to a more technocratic bent as the CIA, Israel, France, the International Atomic Energy Agency, and others variously concluded that Iran might make some form of nuclear progress within a few months or years. For their part, some Iranian officials suggested the program was severely damaged enough to make further access by IAEA inspectors impossible, while others (including Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei) described the damage as modest or even insignificant.

These differing claims and conclusions may stem from a variety of factors, including the difficulty of conducting battle damage assessments for air campaigns against deeply buried sites. Yet the biggest differentiator could be that each of these assessments appears to use different benchmarks for what “reconstitution” might mean. Currently, Iran appears to have four primary options that could credibly be defined as a reconstituted nuclear program: (1) refocusing on foreign civil nuclear cooperation, (2) pursuing a full, declared rebuild, (3) pursuing a full, undeclared rebuild, or (4) revamping the program altogether. These scenarios are discussed separately below, though some elements could be combined to create alternative “in-between” approaches.

Foreign Civil Nuclear Cooperation

Iran confines the program to foreign-supplied reactors and fuel, with limited scientific and research/development activities of its own.

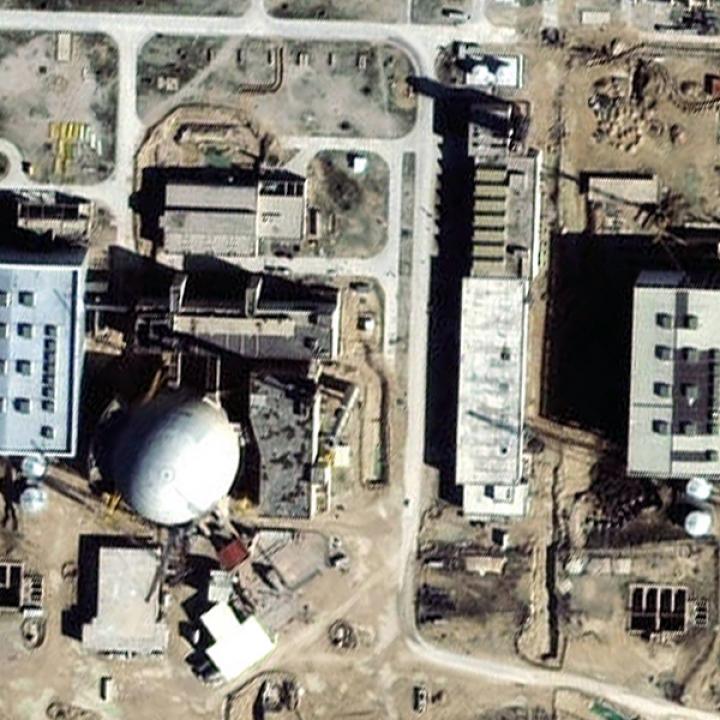

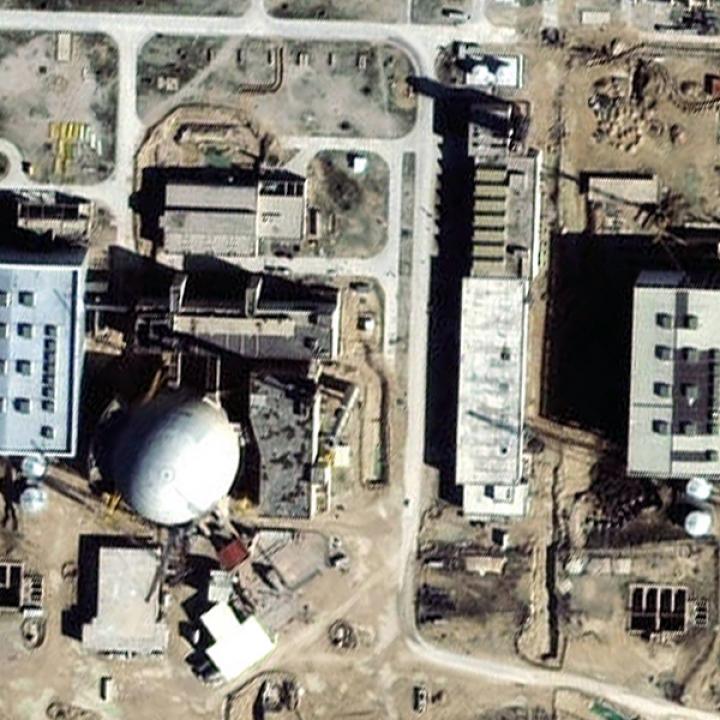

Although much smaller in scope than the other options presented below, this form of reconstitution would still leave Iran with a nuclear program. Namely, Tehran could contract foreign vendors to build additional reactors (supplementing the second reactor that Russia is building at Bushehr) and supply fuel for these facilities. It could also continue with some small-scale research activities, including at its research reactors.

Paying for foreign reactors would be financially costly, but this approach would decrease the risk of losing those assets to war. Notably, the Bushehr power plant was not targeted in June’s hostilities, presumably because (1) it is an operating nuclear reactor that could release radioactive materials if attacked, and (2) it was deemed less likely to contribute to potential nuclear weapons proliferation, since Iran does not possess the technology to extract plutonium from Bushehr’s spent reactor fuel, and any such attempted misuse would be quickly detected.

Although this option could help relieve Iran’s deep concerns about long-term energy needs and reduce the risk of future war, it is probably the regime’s least likely choice. For one thing, it would mark a significant walk-back of Tehran’s previous rhetoric and posture. Iranian leaders repeatedly argued in the past that they could not abandon uranium enrichment because of the blood and treasure the nation had already paid for it, so they are unlikely to make this concession now after a foreign military attack. This option would also enshrine Iranian dependency on foreign nuclear supply—an arrangement that Tehran has come to view as unreliable. Hence, if the regime chooses this route, it would almost certainly be an unstated decision demonstrated by the absence of overt rebuilding work, which would be difficult for the United States and Israel to trust.

Full, Declared Rebuild

Iran restores the program to its pre-June level, with substantial declared facilities for uranium conversion and enrichment as well as expanded plans for domestic reactor construction.

This option would essentially entail relaunching the pre-June program, rebuilding its various components (likely in different, harder-to-attack locations), and opening them to IAEA inspections. Such a program would be time-consuming and expensive, though the idea carries certain political and technological advantages. First and foremost, a program of this scale would enable Iran to continue arguing that its nuclear ambitions are peaceful and fully consistent with its obligations under the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT). Civil nuclear facilities often require more material and equipment than nuclear weapons do, so Iran could aim to construct facilities of a size and scale that would give it a considerable weaponization option while purporting to stay within the space allotted to civil pursuits.

Of course, Tehran realizes by now that even IAEA-inspected facilities could readily be attacked again by Israel and/or the United States if they suspect a proliferation risk. As such, it is unlikely to pursue this type of rebuild absent a longer-term political deal with associated security guarantees—an arrangement that does not appear forthcoming.

Full, Undeclared Rebuild

Iran attempts to restore its uranium conversion facilities, tens of thousands of centrifuges, and other prewar program elements, but without declared facilities open to IAEA inspections.

This option is effectively the same as a declared rebuild, except in this instance Iran would bar IAEA access to its sites in perpetuity or for as long as possible. In doing so, the regime would create ambiguity about its intentions and legal obligations while reaping the benefits of a full, declared rebuild. Yet this scenario would carry the same high costs as the previous option, as well as a higher risk of war given the added justification of flagrant nuclear noncompliance.

Revamp

Iran changes the program’s nature, abandoning “reconstitution” of destroyed capabilities in order to focus on maintaining weaponization options, with smaller facilities and no IAEA declarations.

If Iran intends to pursue undeclared nuclear activities, it is far more likely to redefine the program than repeat its past approach. As noted above, a weapons program can be smaller than a civil energy program. If Tehran wants nuclear weapons but concludes that it will never be permitted to build the large sites necessary for a realistic civil energy program, it may pursue the far cheaper and more secure option of paring its activities down to a smaller, weapons-dedicated enterprise. The facilities needed for such a program could be much smaller, require less nuclear material, and be much more deeply buried and secure because the costs and complications of doing so would decrease. Consequently, this sort of program could be much easier to hide from international observation even if U.S. and Israeli intelligence penetration persists, with the net effect of lessening the risk of future attacks.

Such a revamped program would abandon the pretense of civil nuclear energy, thereby limiting Iran’s ability to persuade the international community that its activities are legitimate. Yet it is unclear whether this factor will matter given the possibility that broad foreign criticism of the United States and Israel may obscure their claims about Iran’s nuclear noncompliance in the long term, even when said claims are accurate. Tehran has also used civil nuclear energy to secure domestic legitimacy for the program in the past, pointing to it as proof that the Islamic Republic is exercising its rights abroad and working to develop economically at home. It is unclear whether the war has reduced the value of this concept to Iran’s leaders.

Policy Recommendations

Iran has many options for reconstitution and probably has not decided which to pursue. At this point, the most important realization is that it could probably develop crude nuclear weapons without rebuilding its program to any significant degree. Iran likely retains enough high-enriched uranium and the chemical processing equipment required to fashion this material into several crude bombs, even if they are not missile-deliverable. Moreover, given Tehran’s frequent emphasis on unconventional defense and force projection via proxies, missiles, and drones, it could make similar unconventional choices about its nuclear armament, particularly in the near term.

These possibilities have multiple implications for policymakers in Washington and abroad. First and foremost, U.S. officials should avoid any further statements calling into question whether Iran could reconstitute its nuclear program. Unless conclusively proven otherwise, the Trump administration should operate on the assumption that Iran has the capability to rebuild the program in some form and may choose to do so. Washington and its partners could then focus on trying to shape Tehran’s choice, guided by four essential priorities:

- Detection: Identifying where and how Iran is working to recreate elements of the program.

- Prevention: Enforcing current export controls and technology transfer prohibitions, which can help reduce Iran’s ability to execute any of these options. The pending “snapback” of UN sanctions will help in this regard, as Iran will remain under nuclear-related sanctions in perpetuity if this measure takes effect as planned next month.

- Education: Ensuring that industry and government figures understand the nature of Iran’s nuclear program, what it is trying to do, and what legal obligations Tehran is still under in terms of avoiding nuclear weapons proliferation.

- Diplomacy: Convincing foreign governments not to contribute to any reconstitution effort that would be inconsistent with Iran’s IAEA and NPT obligations, while simultaneously pressing Tehran to adopt an approach that permits broader use of nuclear energy for civil purposes without the risk of weaponization. A new nuclear deal with intrusive inspector provisions remains the most efficacious way to achieve both of these goals and prevent Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons in the future.

Richard Nephew is the Bernstein Adjunct Fellow at The Washington Institute and former U.S. deputy special envoy for Iran.