- Policy Analysis

- Articles & Op-Eds

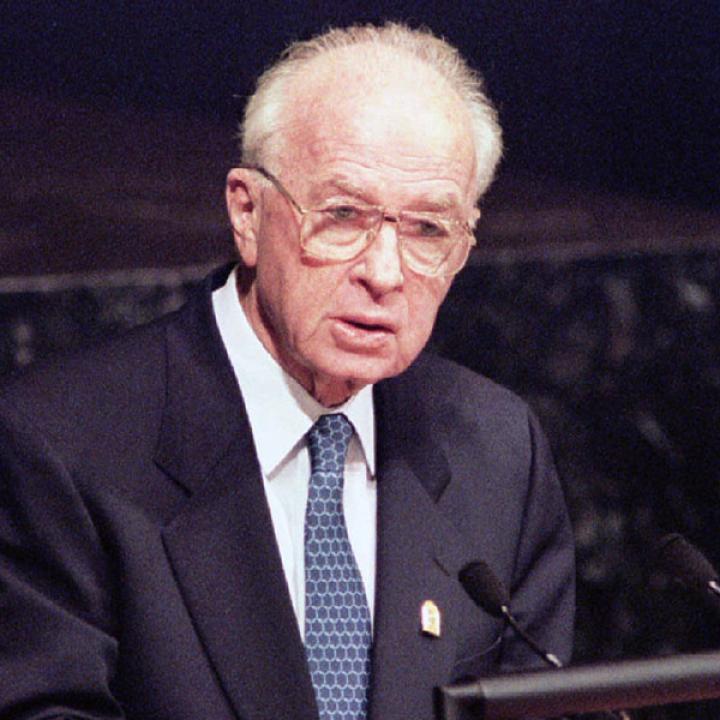

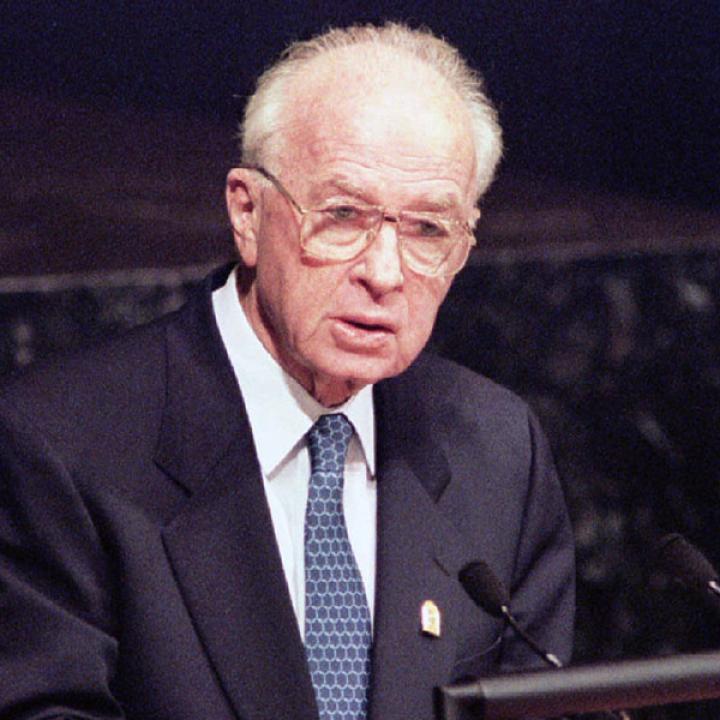

“I Authorized It”: Yitzhak Rabin’s Ethos of Accountability

Also published in Times of Israel

After a failed attempt to rescue a soldier kidnapped by Hamas, the prime minister refused to deflect blame onto other soldiers or their commanders.

Thirty years have passed since the assassination of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin—a moment that still reverberates through Israel’s history. As a journalist, I followed him closely, first as defense minister in the late 1980s and later as prime minister in the early 1990s, interviewing him repeatedly and accompanying him on travels abroad.

Rabin is rightly remembered as a peacemaker. Yet too often forgotten is the soldier who devoted his life to Israel’s security—the former chief of staff who personified the IDF’s ethos of acharai (“after me”). That phrase, evoking the image of a commander leading troops into battle, also reflects a deeper principle of leadership as personal responsibility—achrayut in Hebrew.

For Rabin, responsibility was the essence of leadership. He exemplified traits Israel sorely needs today. For him, accountability meant speaking not only to his political base but to the entire nation in ways both reassuring and painful. Too often, Middle Eastern leaders have equated toughness with telling hard truths only to their enemies. Rabin’s greatness, in no small measure, lay in his willingness to speak those truths to his own people. He addressed Israelis directly about the need to shift national priorities, to curb radicalization, and to pursue regional stability. He rarely told the public what it wanted to hear; instead, he challenged Israelis to hear what they needed to hear.

I remember Rabin’s first speech to the Knesset after being elected prime minister in 1992. He cited the biblical phrase describing Israel as “a nation that dwells alone,” making it clear that this verse was not a blessing but a curse, a warning against isolation. He urged Israelis not to resign themselves to a destiny of eternal solitude but to challenge it—to engage with the world rather than retreat from it. He sought to shift a national mindset that too often settled for yiyeh b’seder—“it will be fine”—instead of striving to make things better.

Yet, even as Rabin challenged the public to take risks, he defined responsibility in the most personal of terms, embodying US President Harry Truman’s famous note to self: “The buck stops here.” Rabin lived that creed instinctively. I remember being present when he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Amid the applause and global acclaim, he did not revel in the glory of winning. He spoke instead of the weight of leadership—the burden of decisions that send soldiers into battle, knowing that some will not return.

Moral Authority

Rabin understood that peace and sacrifice are intertwined. “To preserve the sanctity of life, we must sometimes risk it,” he declared in Oslo. “Sometimes there is no other way to defend our citizens than to fight for their lives, for their safety and freedom. This is the creed of every democratic state.” That same spirit—the courage to risk everything in defense of life—has animated Israel’s struggle over the past two years to rescue hostages and protect its citizens.

Rabin’s moral authority to demand sacrifice derived from his insistence on exhausting every path to peace before resorting to force. He once told me that it was his genuine pursuit of an enduring peace that gave him the strength to look mothers who had lost their sons in the eye. He bore the burden personally.

“I authorized it. I am responsible.” With those words, Rabin addressed the nation after the failed 1994 attempt to rescue Corporal Nachshon Wachsman, kidnapped by Hamas. The prime minister refused to deflect blame onto the soldiers or their commanders. That same year, Wachsman’s mother recalled how Rabin called the family before every holiday and wept with them at the funeral.

This sense of accountability was not episodic; it was fundamental. After authorizing the daring Entebbe rescue in 1976, Rabin quietly drafted a letter of resignation in case the mission failed. Earlier still, he stepped down as prime minister over a minor technical violation, a dollar account his wife had inadvertently kept open from their ambassadorship in Washington. For Rabin, integrity was not a posture; it was the baseline of leadership.

Rabin’s instinct for responsibility defined his life in uniform and in politics. He did not hide behind others when the country needed leadership. Today, as Israel continues to reckon with the trauma of October 7 and the failures that allowed it, Rabin’s example feels especially urgent. The call for an independent national commission of inquiry is not only about understanding what went wrong; it is about restoring a culture of accountability in public life. Rabin’s legacy reminds us that strength is measured not only by deterrence or resolve, but by the moral courage to confront one’s own failures.

What Israel needs most now is not another display of defiance, but a renewal of Rabin’s spirit—a leadership that sees responsibility not as blame, but as duty.

David Makovsky is the Ziegler Distinguished Fellow at The Washington Institute and director of the Koret Project on Arab-Israel Relations. This article was originally published on the Times of Israel website.