On May 19, 2005, Paul Wolfowitz addressed the Institute's Twentieth Anniversary Soref Symposium. Dr. Wolfowitz, former deputy secretary of defense, is president of the World Bank. The following is a transcript of his presentation. Read a summary of his remarks.

So many Iraqis, 8.5 million of them, demonstrated courage on January 30. I want to share two stories that came to me the day after the election from Brig. Gen. Carter Ham, who was our commander in Mosul. Both stories took place in Sunni Arab neighborhoods in that northern Iraqi city.

In one instance, General Ham said voters had gathered outside the polling place but nobody had dared to enter for more than two hours. Finally, one old woman stepped forward and said, "I have waited all my life for this opportunity. I am not going to miss it." She went in and voted, and several hundred people eventually followed her.

In another Sunni Arab neighborhood, it was worse. People were lined up to vote, but someone took a shot at the line of voters and wounded one of them. I cannot imagine what I or most of my fellow Americans would do in those circumstances. What amazes me is what these Sunni Iraqis did. They stayed in line. They moved the line to protect the wounded voter and they stayed to vote.

In those circumstances, what amazes me is not that the Sunni Arab turnout was small, but that people voted at all. That says an enormous amount.

I will take a look at the world from 30,000 feet and make a few brief comments about President Bush's remarkable second inaugural address. He said, among other things, that the survival of liberty in our land depends on the success of liberty in other hands, that the best hope for peace in our world is the expansion of freedom in all the world.

It is a speech that has been widely reported. It has also been widely misunderstood. There are two common misinterpretations, each almost the opposite of the other.

Self-styled foreign-policy realists interpreted the speech as Wilsonian or, in their words, utopian. That is to say, it had no grounding in reality and supposedly is slated for the same sort of failure that President Wilson's vision encountered one hundred years ago.

The speech has sometimes been interpreted from the other direction as ruthlessly realistic, as a signal that the United States is planning to use its military to invade other countries and install democratic regimes friendly to our interests.

Both of these are fundamental misreadings of the president's words, which fit solidly within our real-world experience of the last half-century. Starting in the 1970s, we started to see signs of what has become a truly historic expansion of the realm of freedom and self-government, beginning with the peaceful transformation to democracy in Franco's Spain.

I had the privilege of working with a great American at the State Department, Vernon "Dick" Walters, who was sent on many secret missions by many presidents. Dick was a great raconteur who loved telling stories. One was particularly good. He told it to me several times, more colorfully in person than in his memoirs.

The way he put it was that in 1972, President Nixon sent him to Spain to ask Generalissimo Franco about his plans for the succession. As Walters put it, you could not really look an eighty-two-year-old man in the eye and say, "President Nixon has sent me here to ask you what will happen after you are dead."

[Laughter.]

So beat around the bush a little. He said, "President Nixon is not only the leader of the United States, but he is the leader of the entire free world, and so he sent me here to Spain to ask your views about the future of southern Europe."

Franco looked him straight in the eye, with a rather cold gaze, and he said, "What President Nixon needs to know is what will happen in Spain when I die."

[Applause.]

Things got more remarkable from there. Franco said, "Spain will have a system not too different from what you have in the United States or in Great Britain," apparently unwilling to use the word democracy. He said, "It will be different because we are Spanish, but it will succeed because of three things: the Spanish monarchy; and two institutions I created, the Spanish Army and the Spanish middle class. So you can tell President Nixon that he does not have to worry about what happens in Spain after me."

It was a remarkable statement. A good friend of mine who served shortly after that conversation as President Suarez's first diplomatic adviser told me, "I am no lover of Franco, but what he said is basically true."

It is also a powerful statement about what works best when it comes to democratic transformation. That is to say, it is most successful, and most peaceful, when it comes through the natural growth of institutions that can support democracy.

But it has been a remarkable thirty years since then, starting with Spain, Greece, and Portugal in Europe. The last thirty years have seen the force of freedom literally sweep through whole continents.

For me, it became quite personal some ten years later when I became assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific affairs. If you stop and think about it, only twenty years ago Japan was the only democracy in all of East Asia. Somewhat to my surprise, the Philippines became my major preoccupation in that job. In 1986, a peaceful revolution took place in the Philippines in which the Philippine people came out on the streets by the hundreds of thousands to force President Marcos to leave and bring about the peaceful transition to democracy. It took place through the courage, energy, and drive of the Philippine people, but it took place with a great deal of support from their friends outside, including the United States.

Just one year after Marcos left Manila, South Korea went through a democratic transition that has proved to be durable and extremely successful. In the early 1990s, we saw something that none of us thought we would see in our lifetimes: the peaceful demise of the Soviet Union and the Soviet empire. We saw democracy come to Latin America and to other countries in East Asia, to Taiwan, Thailand, even Indonesia.

It has been a remarkable thirty years in which we have seen things that many of us thought we would never see, and it has not stopped. In just the last few months we have seen that advance continue in such places as Georgia and Ukraine. Perhaps most encouragingly, we have seen some extraordinary expressions of the democratic spirit in the Muslim world -- most dramatically in Afghanistan and Iraq, where more than sixteen million voters risked their lives to cast their ballots.

But it is not only there. Last September, Indonesia, a country dear to my heart, the country with the largest Muslim population in the world, but one that recognizes multiple religions, successfully held a free and fair presidential election. That is often considered a landmark on the road to democracy. In January, the Palestinian Authority held an historic election that has produced new leadership that may finally deliver for the Palestinian people the state they have long deserved.

I very much look forward to the opportunity as president of the World Bank to support people like Palestinian Labor Minister Hassan Abu Libdeh, whom I met with earlier today to advance that effort.

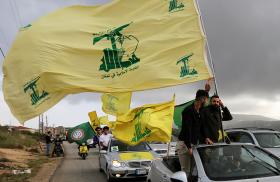

In Lebanon, it was amazing to see how tens of thousands of people came out to demonstrate in the wake of the assassination of the late prime minister Rafik Hariri. The Syrian-backed government in Lebanon resigned under pressure and the Syrian army withdrew. There are still very difficult challenges ahead, but there is a new hope as the Lebanese approach elections next week.

In short, the human desire to choose one's own leaders and to live in freedom is one of the most powerful forces in the world today. It would be the height of unrealism to ignore the great power of that force. Rather, we should support it, we should channel it, and we should use it to make all of us live better and safer and more peacefully.

But it would also be a mistake to believe that this force needs to be frequently assisted by American or any other combat troops. President Bush's goal of ending tyranny in the world is not primarily a task of arms. In fact, I would say it is rarely a task of arms. Indeed, for the most part, those truly revolutionary changes that I have just spoken about took place peacefully and required no combat troops from any nation.

I would leave you with three observations about that history that still apply.

First, great changes can be accomplished peacefully; indeed, it is much better when they can be. Afghanistan and Iraq were exceptions -- necessary exceptions, but hopefully unique exceptions.

Indeed, I go beyond the idea of peaceful change and say that evolutionary change is generally preferable to catastrophic or revolutionary change. The longer evolutionary change is postponed, the greater the chance that some kind of catastrophic collapse will take place. Indonesia today is living through the aftermath of exactly such a catastrophic collapse in 1998 that could have been avoided if former president Suharto had adapted gradually rather than resisting.

Second, and important to me in my new responsibilities, economic development tends to support political development and political change. In no small measure, this is because it leads inevitably to the growth of the middle class. As Franco observed in Spain, the middle class is both the key engine and the key supporter of democratic change. We saw that later in Korea and Taiwan.

Third, to be successful, political transformations need to be accompanied and supported by economic success. Our own history is worth recalling as we look at struggling democracies from Iraq to Afghanistan, from Ukraine to Indonesia.

No country makes the transition to democracy in a single smooth step, and our own history was marked by significant challenges even long after independence. Today we see the challenges of reconstruction in Afghanistan and Iraq, in Rwanda and in a number of other African countries. We see the challenges of economic development and reform in countries as diverse as Ukraine and Indonesia. Those are just a few examples where the success of representative government and free institutions are integrally linked to economic success, as they are in the peace process between Israelis and Palestinians.

Let me conclude by leaving you with this thought: building free institutions is challenging; it takes time; it takes sacrifice; and it takes the support of all of us who are fortunate enough to live in successful societies. Thank you for the support you give.