- Policy Analysis

- Articles & Op-Eds

Netanyahu’s Legacy Won’t Be Made on the Battlefield Alone

Also published in Washington Post

The prime minister has shown historic military resolve, but political courage must come next.

Late one evening, during negotiations over the Hebron protocol in December 1996, Benjamin Netanyahu said to me out of the blue that he was going to “do what Ben-Gurion did.” “You mean Begin?” I asked, thinking that he had misspoken. Menachem Begin had preceded Netanyahu as leader of the Likud party and, like Netanyahu, had originally come out of the Revisionist movement.

“No, Begin didn’t do the big stuff,” Netanyahu answered. “Ben-Gurion did the big stuff.”

Early in his historic political career, Netanyahu was telling me he would make decisions that would be as consequential as those of David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first leader. It was Ben-Gurion who declared Israeli independence, knowing the Arab states would invade and that Israel would have no assured material support from anyone. And it was Ben-Gurion who decided that following Israel’s war of independence, this new fledgling and impoverished state of 600,000 would take in nearly 1 million Jews forced out of the Arab world, because it was its raison d’etre. These were the big, courageous decisions that shaped Israel’s destiny.

Twenty-eight years later, Netanyahu, now Israel’s longest-serving prime minister, has made a Ben-Gurion-type decision in deciding to attack Iran. Until this decision, Netanyahu had been more of a decision-avoider than a decision-maker, always playing for time and believing something would come along to rescue him from the need to make hard choices.

From a political standpoint, his strategy has served him very well. He has been Israel’s prime minister for every year since 2009 except one. He was risk-averse in general, but particularly so when it came to conflict. For example, he favored Qatar providing money to Hamas to keep Gaza quiet—a policy that ended up exploding on Oct. 7, 2023.

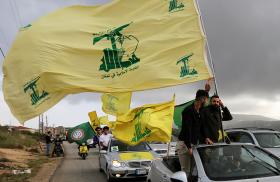

Even after Oct. 7, his risk-aversion did not immediately disappear. He was initially hesitant to authorize a ground invasion of Gaza and would wait 11 months before truly going after Hasan Nasrallah’s Hezbollah in Lebanon.

But Netanyahu’s decision to attack Iran’s nuclear and ballistic missile infrastructure was historic and anything but risk-averse. He knew Iran could inflict significant damage on Israeli cities and towns, with a high likelihood of serious Israeli casualties. That the actual toll was far lower than official Israel Defense Force estimates suggests that Netanyahu fully took ownership of the potentially grave costs of attempting to militarily dismantle Iran’s threat.

Netanyahu has long been obsessed with the Iranian nuclear threat. While Yitzhak Rabin might have been the first Israeli prime minister to raise the question, Netanyahu would bring it up regularly with American presidents going back to Bill Clinton. Even when Netanyahu was out of government, he would emphasize the extent of Iran’s nuclear ambitions, the existential nature of the threat they posed and the need for the world to act to prevent it.

I advised Barack Obama before his initial meeting with Netanyahu in 2009 that this issue mattered far more than any other to him—and that he might even be prepared to make real concessions on the Palestinians if Obama was ready to assure him that the United States would never allow Iran to acquire a nuclear weapon. Obama was at that point not prepared to go that far.

In his 2012 speech to the U.N., Netanyahu declared that Iranian accumulation of one bomb’s worth of uranium enriched to 20 percent was a red line for him. He opposed the Obama nuclear deal—the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action—even though it limited Iran to possessing less than one bomb’s worth of material enriched to only 3.67 percent. Netanyahu’s problem with the JCPOA was that it legitimized Iran having a very large nuclear infrastructure and that its limitations on that infrastructure ran out in 2030. For Netanyahu, that meant Iran was deferring its nuclear weapons option, not giving it up.

Almost a decade and a half later, Netanyahu has now acted on what he considered to be his primary mission as prime minister. He has done so after the Israeli military, on his watch, transformed the regional balance of power by devastating Hamas and Hezbollah, Iran’s most formidable regional proxies, with the Assad regime in Syria collapsing soon thereafter.

But these admittedly breathtaking decisions will not automatically vault Netanyahu ahead of Israel’s founder in the history books. To surpass Ben-Gurion, Netanyahu will need to take these great military achievements and turn them into enduring political outcomes.

And that means tackling Gaza. With Iran hobbled, Netanyahu can now declare he is ready to end the war and withdraw, provided all the remaining hostages—alive and dead—are released. Though no one can doubt that Israel will act again if Hamas seeks to reconstitute itself, Netanyahu now needs to articulate and implement a credible “day-after” plan, especially to ensure there is an alternative to Hamas in Gaza.

Netanyahu has shied away from taking this step because his hard-right coalition partners, including outspoken ministers Itamar Ben Gvir and Bezalel Smotrich, have been staunchly opposed, threatening to bring down his government. But after Iran, Netanyahu has the leverage, not them. And while he must start with Gaza, he must not stop there. He needs to thwart his coalition partners’ plans in the West Bank, where expansive settlement building and legal changes are creating, in Smotrich’s words, “de facto sovereignty“ over a Palestinian population that will never be granted full citizenship.

Such a “one-state solution” is no solution at all, providing instead a sure recipe for forever war. Palestinians will never give up their national identity and will continue to resist. And their resistance will continue to fuel radicalism across the region. One-statism is a clear threat to Israel and the ethics of the Zionist movement. Ben-Gurion refused to seize the West Bank in 1948 (when he could have) because he saw that fateful step turning Israel into a binational, not a Jewish, state.

Ben-Gurion’s greatness stemmed not only from successfully leading Israel in its war of independence but also from how he shaped the country’s destiny in the war’s aftermath. If Netanyahu truly hopes to match or even surpass Ben-Gurion, he will need to see further than his own base to secure a better future for Israel. Doing so will require even more courage and decisiveness than he has already shown on Iran. As I reflect on our remarkable exchange in 1996, I can’t help but think that now is Netanyahu’s moment to fulfill his self-image and “do the big stuff.”

Dennis Ross is the Davidson Distinguished Fellow at The Washington Institute, a former senior official in the Reagan, Bush, Clinton, and Obama administrations, and author of the new book Statecraft 2.0: What America Needs to Lead in a Multipolar World. This article was originally published on the Washington Post website.