Recent gestures, which have included reconciliation talks with Hamas, could strengthen the PA’s Gaza-based rival, further strain relations with its traditional Arab allies, and spur elections with destabilizing results.

The announcement of the normalization agreement between the United Arab Emirates and Israel on August 13, 2020, triggered a flurry of Palestinian Authority (PA) activities that seem to be bringing it closer to its rival Hamas and to the latter’s backers in Turkey and Qatar. These activities are intended by the PA to tactically signal its displeasure to the UAE and Bahrain, and to create a sense of motion as it awaits the results of the upcoming U.S. election. These steps, however, may have significant implications that could stretch the PA’s already strained relations with its traditional Arab allies to a breaking point, strengthen Hamas’s hand, and create dynamics that could force the PA into elections with destabilizing results.

Background

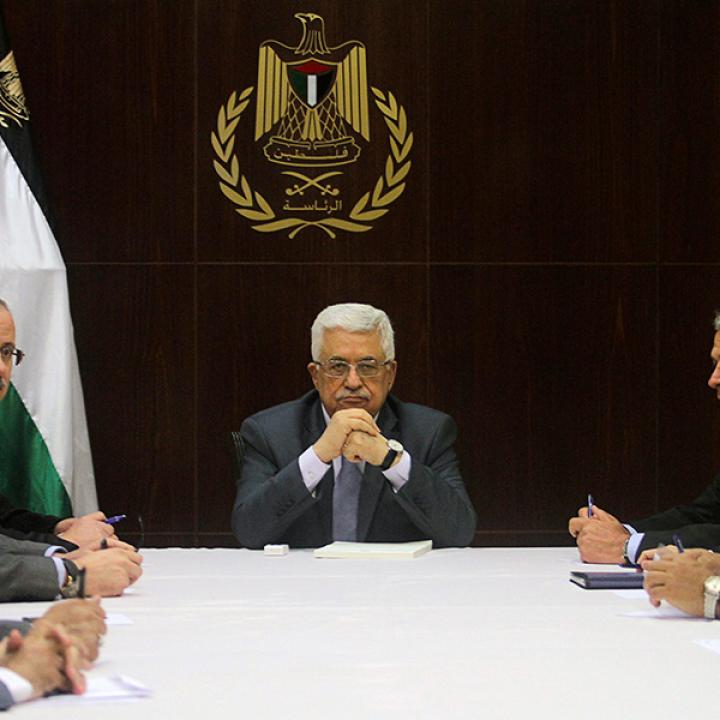

Shortly after the announcement of UAE-Israel normalization, PA leaders launched an intensive engagement with Qatar and Turkey—two countries locked in adversarial relations with the PA’s traditional allies in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, Jordan. Palestine Liberation Organization secretary-general Saeb Erekat called Qatari foreign minister Muhammad bin Abdulrahman al-Thani on August 20; a few days later, on August 24, PA president Mahmoud Abbas confidant Hussein al-Sheikh visited Doha to explore ways to reinforce Qatari support, including financial assistance, for the PA. For his part, Abbas called Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan on August 22. A month later, on September 22, representatives of Fatah and Hamas met in Istanbul and announced a new reconciliation deal, and also agreed on holding parliamentary elections.

The rapprochement with Turkey and Qatar was paralleled by a series of steps that escalated tensions not only with the UAE and Bahrain but also with Saudi Arabia (through the tabling at the Arab League foreign ministers’ meeting of a proposal to condemn the UAE—a proposal that instead highlighted the PA’s isolation by failing to garner any Arab support); Egypt (by shifting sponsorship of reconciliation from Cairo to Istanbul, and most recently by the declaration as martyrs of two Gazan fishermen who were killed by the Egyptian navy); and even Jordan, possibly the PA’s last remaining Arab ally (by ignoring Jordanian entreaties to tone down the rhetoric and diplomatic activities against the UAE).

Tactical Intentions

From Ramallah’s perspective, these moves are not intended as a strategic shift. Abbas is awaiting the results of the U.S. election in November to formulate his new strategy: be that reengaging with the United States through a likely reset by a Biden administration of U.S.-Palestinian policies, or finding a face-saving way to reestablish contacts with a new Trump administration.

There are strong reasons for the PA not to make such strategic shifts. Diplomatically, Qatar and Turkey are unable in the long term to substitute the financial and political support provided by the PA’s traditional Arab allies. Instead, the PA’s recent measures fit President Abbas’s modus operandi and mirror similar tactics that have worked for him in the past. For example, after the move of the U.S. embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, Abbas intensified his contacts with Erdogan to pressure Saudi Arabia into taking a more robust position, after which the PA returned to Riyadh’s orbit.

Politically, Abbas’s enmity of Hamas is deep, and the root causes of the split—Hamas’s weapons arsenal and an irreconcilable disagreement on fundamental political platforms—remain unaddressed. Again, there is precedent to this approach vis-à-vis Hamas. In 2017, after agreeing to a reconciliation deal sponsored by Egypt, Abbas managed to find ways to avoid implementing it. Indeed, despite the recent announcement of the Fatah-Hamas agreement on holding elections, and in an effort to preserve some room for maneuver, Abbas has not as of this writing issued a formal decree calling for elections.

Rather than denoting a strategic shift, these maneuvers serve two purposes. First, they are meant to signal the PA’s displeasure toward the Arab reaction to the normalization deals, evident in the PA’s threat to move to an alternative axis in an effort to pressure those states. Second, they are a means of creating diplomatic and political motion, ultimately buying time until November. Domestically, the reconciliation talks are aimed at satisfying a Palestinian public that is both angered by the normalization deals and frustrated with its own leadership’s lack of initiative. Additionally, those leading the efforts on either side have their own political objectives: Jibril Rajoub on the Fatah side hopes this will improve his standing in the contest to succeed Abbas, while Saleh al-Arouri of Hamas is positioning for the movement’s internal elections, which are slated for 2021.

Strategic Implications

Although the PA may see its recent moves as mere tactics, the results may end up severely limiting its strategic options and pushing it into a corner. Diplomatically, there is currently little patience in key Arab capitals for Palestinian leaders. Since the PA embarked on its vociferous campaign against the UAE and, later, Bahrain, Gulf—and, to a lesser extent, Egyptian—media outlets have been replete with articles attacking Palestinian officials. A recent lengthy interview by Al-Arabiya TV with former Saudi ambassador to the United States Prince Bandar bin Sultan al-Saud was an unmistakable signal of Riyadh’s displeasure with PA leadership. Even Jordanian officials have privately expressed frustration with Abbas’s approach.

In such fraught circumstances, continued overtures to Ankara and Doha may well prompt Arab leaders to further downgrade their own relations with the PA, leaving Abbas with no way back to the fold and effectively forcing the PA closer to Turkey and Qatar. This situation could be further exacerbated if either Turkey or Qatar uses the Palestinian issue to stoke its rivalries with Saudi Arabia and Egypt.

Domestically, reconciliation is generating its own momentum; thus, the further it proceeds, the higher the political cost for the PA to walk away from it. That momentum, coupled with pressure from Turkey and Qatar, may prove too strong for Abbas to resist holding elections. Holding elections without resolving the underlying causes of the rift—namely, commitment by all participants to the two-state solution, renouncing terrorism, and addressing Hamas’s militias—could deepen the Palestinians’ international isolation in a manner similar to that which followed the 2006 Palestinian Legislative Council elections.

A scenario that sees the PA shifting toward the Turkey and Qatar axis could prove disruptive. Both states are close associates of Hamas. Qatar is the group’s main financial backer in Gaza—a role allowed by Israel to prevent a humanitarian and security collapse in the coastal strip—and hosts some of its leaders. Turkey provides political support to the movement and has reportedly gone so far as to grant some Hamas members Turkish passports. Furthermore, such a shift could weaken the moderating influence of the PA’s traditional allies. Loss of Arab financial support would intensify the economic crisis in the West Bank and lead to more volatility. In addition, reintroducing Hamas to the PA not only will cause the PA’s international isolation, but also could terminate Palestinian-Israeli security cooperation—a key reason for the relative security stability in the West Bank—and raise concerns in Jordan. Israel has already warned the PA about the implications of bringing Hamas back to the West Bank.

To avoid these outcomes, key Arab capitals—primarily Amman, Cairo, and Riyadh—need to send a clear message to Ramallah about the cost of its current trajectory, while engaging the PA on ways it can benefit from the new trend of Arab-Israeli normalization. Individually, Jordan and Egypt have already communicated their concerns to Ramallah, but with little impact, highlighting the need for a coordinated approach. Jordan, given its special relationship and leverage with the PA, can play the lead role in managing this exchange, but it can do so only with Saudi and Egyptian support.

There is little that the United States can do directly to impact these dynamics because the PA has severed all contacts with the Trump administration in protest of its policies, especially those regarding Jerusalem. For its part, the United States has already cut aid to the Palestinians and cannot use assistance as leverage. Washington should instead privately encourage its regional allies to adopt a coordinated approach.

Ghaith al-Omari is a senior fellow at The Washington Institute.