A Troubling Letter to an Unbending Ayatollah

Who wants a nuclear deal more: the Iranians, or the Obama administration?

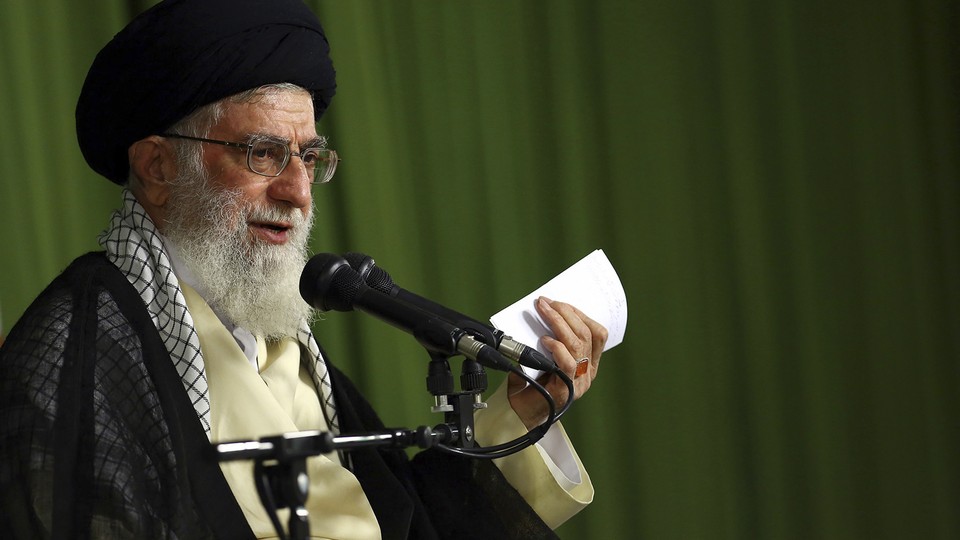

The Wall Street Journal’s Jay Solomon and Carol Lee reported this week that President Obama recently wrote a letter to Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the Iranian supreme leader, in which he laid out the benefits for Iran of a nuclear compromise.

“The letter appeared aimed both at buttressing the campaign against Islamic State and nudging Iran’s religious leader closer to a nuclear deal,” the Journal reported. “Mr. Obama stressed to Mr. Khamenei that any cooperation on Islamic State was largely contingent on Iran reaching a comprehensive agreement with global powers on the future of Tehran’s nuclear program by a Nov. 24 diplomatic deadline.”

This is, by most counts, the fourth letter President Obama has written to Ayatollah Khamenei. He has received approximately zero responses. There are two ways to interpret this asymmetry. The first is to conclude that Obama is chasing after Khamenei in the undignified and counterproductive manner of a frustrated suitor. The second is to conclude that Obama is cleverly boxing-in Khamenei in the court of international opinion: When the nuclear talks collapse, the administration will at least be able to say: We tried. We reached out repeatedly to the supreme leader, in whose hands nuclear decisions ultimately rest, and he spurned us, and spurned us again.

Both of these conclusions track with reality, but both are incomplete, because we do not know the tone of these letters, or much about their substance. What we can reasonably assert, however, is that the letter will not have its intended effect. Quite the opposite, according to the Brooking Institution's Suzanne Maloney:

[T]here is simply no plausible scenario in which a letter from the President of the United States to Ali Khamenei generates greater Iranian flexibility on the nuclear program, which the regime has paid an exorbitant price to preserve, or somehow pushes a final agreement across the finish line. Just the opposite—the letter undoubtedly intensified Khamenei's contempt for Washington and reinforced his longstanding determination to extract maximalist concessions from the international community. It is a blow to the delicate end-game state of play in the nuclear talks at the precise moment when American resolve was needed most.

This most recent letter was delivered at an unfortunate moment in the run-up to the putatively climactic negotiations between Iran and world powers scheduled for later this month. The Obama administration has already given the impression that it wants a nuclear deal more than Iran wants a nuclear deal. The U.S. has good reason to want a strong agreement: It could prevent a nuclear-arms race in the world’s most volatile region; it could protect America’s allies, including and especially Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates; it could help ensure that Iranian-sponsored terrorists are denied the protection of a nuclear umbrella; and so on. But it is Iran that actually needs a deal more than the U.S. Its economy has nearly been crushed by American-led sanctions, and the ruling regime understands that further domestic economic hardship could pose a threat to its existence.

And yet, it appears, superficially at least, that it is the U.S. that is bending to the demands of Iran. The most recent example comes via official Iranian-state media, which reported that U.S. negotiators have agreed to allow Iran to run 6,000 uranium-enriching centrifuges, which is up from the previous maximum American concession, 4,000, proposed just two weeks ago.

Iranian negotiators could take such premature concessions as signs that more concessions are coming, in exchange for … not very much. Certainly, no broad shift in Iranian strategic thinking seems likely. As Michael Singh, of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy recently observed, “(T)he changes in U.S.-Iran relations have been decidedly one-sided. The central aim of American policy toward Iran in recent years had been to persuade Tehran to make a strategic shift: away from a strategy of projecting power and deterring adversaries through asymmetric means, and toward one that would adhere to international norms and reinforce regional peace and stability. Détente—and, for that matter, a nuclear accord—resulting from such a shift would be welcome by not only the U.S. but also its allies in the region and beyond. Iran does not, however, appear to have undergone any such change.”

The most potentially damaging aspect of this latest Obama letter is that U.S. allies in the Middle East weren’t informed of its existence. Given the dysfunctional nature of the U.S.-Israel relationship right now, I doubt that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was particularly surprised to be surprised in this manner.

But America’s Gulf allies could legitimately feel some level of disappointment. These countries, which face twin threats—from Shiite extremism in the form of the Iranian regime, and Sunni extremism, in the form of the Islamic State terror group, or ISIS—count on the United States to protect them from both. Lately, and uncharacteristically (particularly in the case of the Saudis), they are actually helping the U.S. fight extremism. The Saudis and Emiratis are both currently participating in attacks on ISIS. In other words, they are part of an actual wartime alliance led by the United States. It would have been appropriate for the Obama administration to let its friends know that it was reaching out, again, to one of their enemies. The Gulf allies are already paranoid about U.S. intentions toward Iran. Now they are more paranoid.

It would help, of course, if we could see the contents of the letter, and read it for tone. Since we don't have it—yet—all I can do is hope that it says the following:

Dear Ayatollah Khamenei,

I hope the family is well. Now on to business. Here’s the deal—I’m the best thing you’ve got going. If you don’t agree to a deal that shelves your nuclear program, I’m going to crush your economy. You think sanctions are bad now? Just wait. I’ll have just about every member of Congress, and a majority of the American people, behind me. Even if I didn't want to crush your economy, the U.S. Senate would do it anyway. And while we're crushing your economy, by the way, I’ll be reminding you that all options remain on the table. If you know what I mean.

If you agree to a deal (and this is a deal that will preserve your dignity and your country’s ability to maintain a peaceful, transparent, nuclear program), then we set that table in a very different manner. We can talk about ISIS, and economic integration, and whatever else you want to talk about. But if you don’t agree to a deal that puts you very, very far away from nuclear breakout, the future of your country, and its government, will be in doubt. Most American politicians—certainly most of the people running to replace me—aren’t interested in dealing with you at all. I am. I don’t need this deal—our economy is fine, especially compared to yours. You need this deal. So think about what I'm saying carefully.

The Iranians originally came to the negotiating table because U.S.-led sanctions were hurting them badly. I understand the need for give-and-take in negotiations, but I’m getting worried that the U.S. is focused too much on the first half of that equation.