Story highlights

NEW: A foe says Morsy's amassing of powers "can only lead to a dictatorship"

A Morsy backer says the president has "overwhelming" support from Egyptians

The president's order makes his decisions immune from judicial oversight

Many courts close in protest, and there are concerns about the economic impact

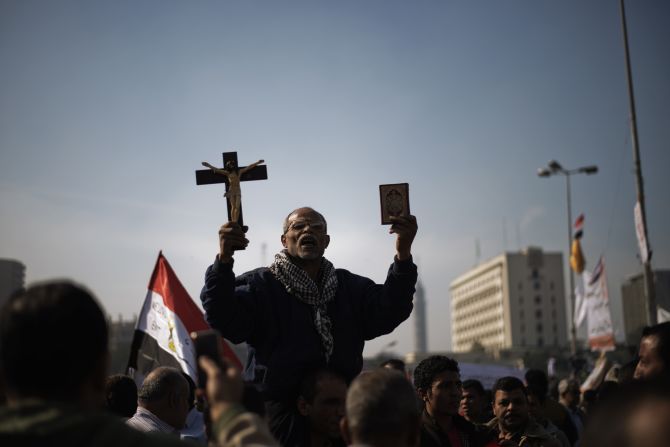

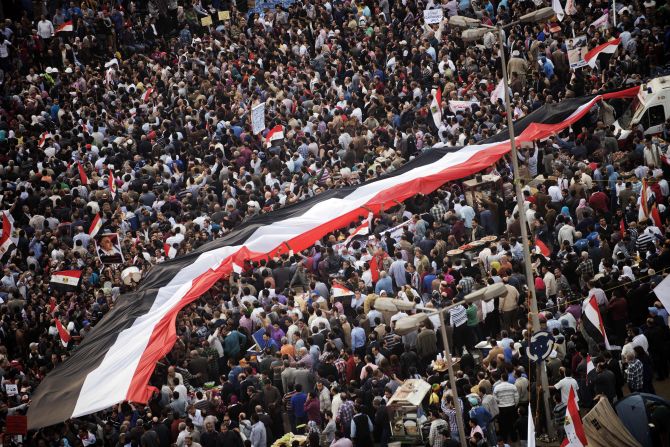

The sun rises over Cairo, and the city’s landmark Tahrir Square is buzzing. Not with traffic, not with commerce, but with protest – a tent city packed with people rife with anger at a man they blast as a dictatorial president, one who put amassing power for himself and his supporters over the good of his country.

Weren’t things in Egypt supposed to be different now?

No longer railing against Hosni Mubarak, who was forced out amid popular unrest, demonstrators now direct their anger at the first man since Mubarak to be the North African nation’s president.

Other things aren’t much different than in January 2011: Egypt’s economy is still staggering, police have clashed with protesters, and the political future is uncertain. What remains to be seen is whether those who decry Mohamed Morsy as “the new pharaoh” will manage to oust him from power, as happened to Mubarak.

In a country without a constitution, Morsy already has the powers of both a president and a legislature after the elected parliament was dissolved.

But it was his edict last Thursday – declaring that Egypt’s courts cannot overturn decisions he’s made since coming to office in June or over the next six months, nor can they alter the makeup or work of the 100-person group charged with crafting a new constitution – that prompted his opponents to take to the streets.

Morsy insists he’s trying to protect Egypt’s fragile Arab Spring revolution, not accumulate unchecked power. His moves “cemented the process that would create the institutions that would limit his power, define the constitution and have parliamentary elections so that we can say this is a democracy,” said Jihad Haddad, a senior adviser in the Freedom and Justice Party, the political arm of the Muslim Brotherhood.

Edict divides Egypt, unifies opponents

But that’s not how his political foes – whom many members of the Brotherhood, a once-banned Islamist movement that Morsy led, see as “heretics,” according to Washington Institute for Near East Policy fellow Eric Trager – look at the situation.

Former U.S. diplomat Jamie Rubin said Morsy’s edict “brings to mind all the fears that people in that part of the world have had about the Muslim Brotherhood when it comes to democracy.”

Amr Hamzawy, who’d been in the now dissolved parliament, said action is needed to prevent more “suffering” under a president with “sweeping powers,” as Egypt had for 60 years under men like Mubarak, Anwar Sadat and Gamal Nasser.

“Morsy is the … president who has sweeping executive (power), sweeping legislative (power) and … puts himself above the judicial branch of government,” said Hamzawy, founder of Egypt’s Freedom Party. “That is a very dangerous mix, which can only lead to a dictatorship.”

Intent on not letting that happen, people around the country have staged protests and stormed Muslim Brotherhood offices over the past six days – sometimes with violent results, with hundreds being reported injured and one killed in confrontations with security forces and Morsy’s backers.

Tuesday has been forecast as the opposition’s biggest show of force yet, with major rallies set for Cairo and elsewhere around Egypt. It’s a chance to show, as former Finance Minister Samir Radwan said to CNN, that “the whole population of Egypt is against” Morsy and his supporters.

On Monday, the Muslim Brotherhood scrapped its own million-man counterprotest “to avoid any problems due to tension in the political arena,” said spokesman Mahmoud Ghozlan. State TV announced the demonstrations were called off “to avoid bloodshed.”

Analysis: Morsy makes his move

Yet this move doesn’t mean Morsy and his allies think they won’t prevail, or that they feel Egyptians aren’t on their side.

Senior presidential aide Essam El-Erian calls concerns about Morsy’s edict overblown, blaming the protests on “counterrevolutionary forces” loyal to Mubarak’s party. Haddad says polls show “an overwhelming majority supporting President Morsy and his decisions.”

Whomever one believes, and whatever most Egyptians think, there’s been little indication that either side will back down. And the longer the tension persists, the more chance it will have a negative impact on the country.

In response to what he described as “the most vicious … attack on the judicial authority’s independence” ever, only seven of Egypt’s 34 courts are still operating and 90% of its prosecutors have gone on strike, said Judge Mohamed al-Zind of the Egyptian Judge’s Club.

On Monday, Morsy met with members of Egypt’s highest judicial body, the Supreme Judicial Council, which has been critical of his edict.

Afterward, Haddad said the decree was “clarified” – not overturned or altered – to reflect that Morsy “did not give himself judicial power” but did provide “immunity for his presidential decisions.” He added “the president himself (is) not immune from judicial oversight,” though it wasn’t clear in what instances or if there was anything preventing Morsy from issuing a new decree so this could not happen.

Beyond the judiciary, there are concerns about how fresh popular unrest will affect an already-fragile economy, where about 25% live in poverty, and stock market values plunged after Morsy’s announcement.

“The majority of the people are really suffering, and they were looking forward to some stability,” said Radwan, who served under Mubarak as well as in the government that followed him. “I’m afraid that this constitutional declaration has blown it up.”

The next few days and weeks could produce more stalemate, more violence or more uncertainty. But experts say, even if things remain peaceful, how the country’s new constitution takes shape may prove critical to its future.

There has also been growing turmoil about the constitutional panel, pitting conservatives who want Egypt to be governed by Islam’s Sharia law against moderates and liberals who are making it a higher priority to ensure basic freedoms, including for women.

Morsy to meet with top judicial body

With the Muslim Brotherhood’s increasing hold on power, non-Islamists may increasingly walk away from that process, leaving the path open to a constitution embracing the Brotherhood’s view of an Islamic state in Egypt, according to Trager.

“By the time you get that new constitution, it will have been written by an Islamist-dominated assembly that all non-Islamists have completely abandoned, and the new parliamentary elections will likely exclude members of the former ruling party who posed the greatest threat to his authority,” he said.

Hamas leaders in Egypt for cease-fire talks

CNN’s Reza Sayah and journalist Mohamed Fadel Fahmy reported from Cairo, Egypt. CNN’s Michael Pearson, Greg Botelho and Jason Hanna also contributed to this report.